And the Lord said: I have seen the affliction of my people in Egypt, and I have heard their cry from their leaders; I know his sorrows and I am going to deliver him from the hand of the Egyptians and bring him out of this land to a good and spacious land where milk and honey flow, to the land of the Canaanites, the Hittites, the Amorites, the Perizzites, the Hivites and the Jebusites.

Exodus 3:7-8

Jews are perhaps the only people on the planet whose relationship with God is like a family one.

The Lord God of Israel is prone to offense and fits of anger, he is difficult to please, but he will always protect those who are faithful to him. The story of the Exodus, a foundational Jewish myth and one of the greatest epics in human history, is a story about the difficulty and yet honor of being chosen by the people. And it’s impossible to imagine how difficult it is to be the main prophet and leader of this people. The history of the journey of the Israeli (Jewish) people to Palestine from Egypt, where they were in slavery, is described in the book of the Old Testament, which is called Exodus in Latin and “Exodus” in Russian. This is the second book of the main sacred body of Jewish texts - the Torah. In total, the Torah includes five books: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. Called the Pentateuch, they form the beginning of the Old Testament. The authorship of the Exodus in the Jewish tradition is attributed to the prophet Moses himself - although in this case it turns out that he described in the text his own death and funeral.

The fact that Exodus immediately follows the book of Genesis, which tells of the creation of the world, the expulsion of the first people from paradise, the Flood, and the founding of the people of Israel by the patriarch Abraham, speaks of how important this book was for the Jews. In fact, the Exodus is the story of their formation as a nation, acquiring their own laws and state. Of course, all this was sent by God Yahweh, which means it is sacred and inviolable.

Here's what the Bible says about it.

Artists of the 18th-19th centuries loved to depict a large-scale picture of the exodus of the Jews from Egypt. Looks really very majestic

This whole story began with a Jewish youth named Joseph, the son of Jacob. Jacob, the grandson of the forefather Abraham, once fought with God himself in human form and defeated him, for which he was called Israel - “God’s rival.” Then the people who descended from him began to call it that way. Joseph, nicknamed the Beautiful, an intelligent and talented young man who could deftly interpret dreams, was close to the pharaoh, and thanks to him, the Jews in Egypt lived very well.

But the years passed, Joseph died, there were more and more Jews (10-15 children in a family was the norm), and the new pharaohs began to think that in fact they did not owe the Jews anything. So the Egyptians forced the Israelites to do hard work and eventually enslaved them.

The Israelites were enslaved for more than two centuries, all the while comforting and encouraging each other with the legend of their coming salvation. Meanwhile, the next Pharaoh, seeing that the slaves did not stop multiplying, ordered the killing of all newborn Jewish boys. A woman named Yocheved, in desperation, put her baby in a wicker basket and sent it floating down the Nile in the hope of divine salvation. But, as they say, trust in God, and do not make a mistake yourself: Yocheved sent her eldest daughter Miriam to look after the baby.

Oddly enough, the crocodiles were not interested in the baby, but the pharaoh’s daughter, who was relaxing by the river, was. The princess ordered the maids to get the basket with the baby and, on the advice of Miriam, who very opportunely jumped out of the coastal bushes, found a Jewish nurse for the boy - she turned out to be, as you might guess, Yocheved.

Moses caught from the water, Pharaoh's daughter and Miriam who happened to be nearby

But that was just the beginning of the story. When the boy adopted by Pharaoh, who was named Moses (“Moshe” means “drawn from the water”), grew up and learned the plight of his people, the first thing he did was kill the Egyptian overseer who mistreated the Hebrew slaves. Pharaoh drove Moses out of the country.

During his wanderings outside of Egypt, Moses managed to get married and have two sons. One day he saw a bush in the desert that was burning without being consumed (“burning bush”). From the bush came the voice of God, who called Moses to return to Egypt and lead his people from there. He was promised the land of Canaan to inhabit, also known as the Promised Land (that is, “promised”).

Pharaoh, naturally, did not agree to release the numerous free labor to God knows where. Then God unleashed a series of natural disasters and diseases on the country, called the Ten Plagues of Egypt. After the tenth, Pharaoh finally realized that Moses and his brother Aaron were not joking, and the Jews were allowed to leave.

Many miracles awaited the chosen people along the way: they crossed the Red Sea along its bottom (God, at the request of Moses, parted the waters and closed them again, drowning the Egyptian pursuers), received food directly delivered from heaven (“manna from heaven”) and laws from the same place, Moses extracted water by striking his staff against a rock... But for some reason all this was not enough to prevent the Jews from doubting their God and starting to worship a calf smelted from gold.

In the end, they annoyed God with their unbelief and he cursed his people, declaring that none of those who came out of Egypt would see the Promised Land - it would be found only when everyone who had been in slavery died. So the Jews had to wander in the desert for forty years, and Moses himself died, seeing Canaan only from afar. After this, the Israelis began to conquer new lands, but that is a completely different story.

The most amazing thing about this grandiose legend is that it may have been made up from beginning to end. Although, it would seem, remove divine intervention from history and declare everything that cannot be explained without divine intervention as happy or tragic accidents, and the history of the great migration of an individual people is ready.

But the problem is that the Exodus of the Jews is not confirmed by archaeological finds. There is no mention of a man named Moses or his brother Aaron in ancient Egyptian texts. On the Sinai Peninsula, dug up by archaeologists far and wide, no traces of the movement of a huge group of people were found. In modern Israel and Palestine, on the territory of which the ancient fortress city of Jericho is located (its destruction with the help of loud sounding trumpets is described in Exodus), no traces of a mass invasion were also found: the local inhabitants undoubtedly fought wars, but no new settlements were established by outsiders founded and did not bring their culture to these cities. Moreover, there is evidence (indirect - in the Bible itself) that the Semites lived in these places from time immemorial and did not come here from anywhere.

Ramses II, Akhenaten, Hatshepsut - three contenders for the role of pharaoh who did not want to let the Jews go

All attempts to find confirmation of the Exodus in historical events rest only on “indirect evidence.” For example, light-skinned slaves depicted in some wall paintings in the tombs of noble Egyptians are interpreted as Semites. The pharaoh under whom the Exodus took place is identified as the powerful Ramses II the Great, a 19th Dynasty pharaoh who reigned approximately 1279–1213. BC e., - and are based only on biblical references to the fact that this pharaoh ruled for a very long time. Under Ramses II, Egypt reached its greatest prosperity, coming as close as possible to what is commonly called an empire - both in terms of the area of the state, and in the number of conquered peoples, and in material wealth, and in monumental art. Recently, another version has become popular - that the Jews left Egypt under his son Merneptah. And the princess who picked up baby Moses is identified as Termutis, the daughter of Ramses II by one of his concubines.

Stele of Merneptah

But the written sources on which the supporters of these hypotheses are based are difficult to unambiguously interpret. In 1896, the so-called “Stela of Merneptah” was found in Thebes - the Egyptians often made such steles as monuments to the military victories of certain pharaohs: at the top is a picture of the pharaoh trampling on his enemies, and at the bottom is a detailed description of the achievements. The text on the Merneptah Stele describes the pharaoh's successful Libyan campaign, but mentions one Isiriar or Isirial among the defeated peoples or cities (there is disagreement regarding the reading of the hieroglyphs). Some experts interpret this as a description of an armed clash on the shores of the Red Sea, which the Egyptians, in the best traditions of all times and peoples, portrayed as the defeat of the enemy followed by his panicky flight. But this hypothesis seems rather far-fetched.

Another work that supporters of the historicity of the Exodus rely on is the “Speech of Ipuwer,” one of the most famous texts of ancient Egyptian literature. But its historicity is also questioned.

The manuscript of the “Sayings of Ipuwer” is a written source in which confirmation of the reality of the Exodus is sought and even sometimes found

“The Speech of Ipuwer” exists in a single copy - on a badly damaged papyrus dating back to the 19th dynasty. This is a powerful poetic text that depicts some terrible disasters that befell the Egyptian land - the seizure and plunder of beautiful cities and temples by both foreign barbarians and the Egyptian mob, crop failure and famine, illness and death, corpses in the Nile Delta, mass infertility of women and others horrors. Parallels are often drawn between the events described in the “Speech” and the Ten Plagues of Egypt, which God brought down on the country of Pharaoh, who did not want to let the Jews go.

Many years of attempts to find a historical correspondence to what is described in the text have so far been unsuccessful. The most widely accepted view now is that of the German Egyptologist Gerhard Fecht, who in 1972 interpreted the Ipuwer Oration as a later copy of a text produced during the First Intermediate Period, the so-called “Dark” Period (2250–2050 BC). During this era in Egypt, power passed from the hands of the pharaohs to the city governors-nomarchs, who were unable to maintain order in their lands - in fact, anarchy and lawlessness reigned in the country. The country split into 24 separate nome districts, the unified irrigation system connected to the Nile was destroyed, which led to famine and riots in the cities.

There is another hypothesis, according to which “Ipuwer’s Speech” is nothing more than a work of art. This may be a description of the Kingdom of the Dead: the German scientist Ludwig Morenz sees parallels in the “Speech” with the ancient Sumerian “complaints of the dead” - a special genre of ancient poetry designed to emphasize that it is still better on earth than in the afterlife. Also, unknown to us, Ipuver can act as a prophet, describing some imaginary disasters of the future - this explains the sublime intonations and logical confusion of the narrative.

King Sargon, who was a “basket boy” long before Moses

However, scientists are looking for parallels between the Book of Exodus and history more for entertainment than for serious evidence (and Jews simply believe). Something else is more curious. The fact is that this legend contains many wandering mythological and fairy-tale motifs, as well as historical ones, but borrowed from other cultures. Thus, the laws brought by Moses from Mount Sinai (and he brought from there not only the tablets with the Ten Commandments) in some places echo the Code of Hammurabi.

And the story of the rescue of baby Moses from the water almost literally coincides with the more ancient legend about the childhood of the Akkadian king Sargon - this great ruler, known both as a military leader and as a builder of temples, was of low origin. The inscription on one of his statues describes how he, being born into a poor family, came to his adoptive father.

My poor mother conceived me and gave birth to me in secret. She put me in a reed basket and sealed my door with mountain resin. She threw me into the river, the river did not drown me. The river lifted me and carried me to Akki, the irrigator...

In a word, it is very likely that the myth of the Exodus was created already at a time when the Semitic kingdoms of Israel and Judah, also known as North and South, were conquered first by the Babylonians and then by the Persians. The people of these kingdoms desperately needed to preserve their culture, language and worship of one God under the yoke of the conquerors. From the fragments of historical legends, a whole canvas was assembled about how this very God took care of his people, saving them from slavery and giving them a beautiful land for eternal possession.

The Babylonian captivity of the Jews, unlike the Egyptian one, is confirmed by archeology

The hypothesis put forward by Hebrew historian Stephen S. Russell paints a pretty neat picture of how the puzzle pieces might have come together. The northern kingdom of Israel preserved the traditions of nomadic pastoralists who could often migrate to Egypt and back, depending on the crises that periodically overtook this country - so the very idea of \u200b\u200bthe Exodus could belong to them. And the southern kingdom of Judah was busy with frequent wars with Egypt and its neighbors, so it belongs to those pages of Exodus, which tell about the military victories of the chosen people over the inhabitants of the Promised Land.

What if the Ten Plagues of Egypt really happened? More precisely, this way: if they were real, what could cause them?

A group of European and American biologists, led by the chief epidemiologist of New York, John S. Marr, once asked approximately this question. In 1996, based on this research, Marr wrote the article “Epidemiological Analysis of the Ten Plagues of Egypt,” which later, in turn, became the basis of a documentary film. Fascinated by the topic, the epidemiologist composed and published the successful techno-thriller “The Eleventh Plague” - about a mad scientist who intends to repeat the effect of biblical plagues in our time.

The hypothesis of Marr and his colleagues was based on the assumption that the Ten Plagues began with a powerful volcanic eruption, accompanied by an explosion. What happened next?

Watching the sunrise on Mount Sinai is a popular tourist attraction, fortunately tourists are not in danger of a volcanic eruption

- Rising water temperatures caused phytoplankton to turn red, a phenomenon known as “red tides” (“water turned to blood”—the first plague).

- Toxins released by plankton caused a mass exodus of toads, which infested the houses of Egyptians living near the water (second plague).

- The fish that died from the same toxins brought to the river hordes of midges of the genus Culicoides, carriers of infection, and gadflies, stinging people and livestock (this phenomenon is divided into two - the third and fourth plagues).

- Due to the infection carried by midges and gadflies, livestock naturally died out and skin abscesses developed in people (the fifth and sixth plagues)

- Thunder, lightning and the fall of red-hot stones from the sky (“hail of fire” - the seventh plague) are the direct consequences of the volcanic explosion finally brought to the attention of the Egyptians.

- The same wind that brought the catastrophic thunderstorm brought locusts to Egypt, devouring all the crops (eighth plague).

- The same volcano caused a weather anomaly, and the destroyed plants could no longer hold back the soil - so a sandstorm arose, eclipsing the sun (this is the ninth plague - “Egyptian Darkness”).

- The grain that was still in stock contained locust excrement, which infected it with the fungus Stachybotrys chartarum. Fungal toxins poisoned the top layer of grain. And in the Egyptian tradition, the eldest sons were the first to receive food at the table (they were also entitled to a double portion), and the strongest young animals were the first to get to the feeder. They were the ones who were poisoned by toxins. The Book of Exodus describes this as the tenth plague, killing all the firstborn of Egypt.

Thus, divine executions, as interpreted by scientists, turned into a catastrophic natural phenomenon with devastating consequences that deprived the Egyptians of food and struck them with diseases. The fact that Jews survived this catastrophe could be a later insertion into the story of a real terrible event.

The volcano from which all this began could be Santorini - it was its eruption and explosion that destroyed the Minoan civilization of Crete (the same one that built the Palace of Knossos with its labyrinth and the Minotaur). All this reached Egypt in the form of a tsunami wave, an ash cloud and a thunderstorm. By the way, the waters of the Red Sea that parted for the Jews could also have been a consequence of the tsunami.

Another potential culprit for executions is the Alal Badr volcano in Saudi Arabia. He is also considered the main candidate for the role of Mount Sinai, given that during Moses’ conversation with God, the top of the mountain was enveloped in a thundercloud full of lightning. The identification of the currently existing mountain of the same name with the site of biblical events goes back to a later tradition.

The idea of monotheism (monotheism) was not invented by the ancient Jews. The first to gain such a divine revelation was the Egyptian pharaoh Amenhotep IV from the 18th dynasty, who went down in history under the name Akhenaten. The change of name was due precisely to the fact that the pharaoh wanted to reject the old gods: Amenhotep means “Amon is pleased” (Amon is the sun god, better known as Ra), Akhenaten is “useful to Aten” (Aten is the only Sun god, not supreme, and replacing all gods). Was it not from him that Moses borrowed the idea of monotheism?

The founder of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud, was the first to express this idea in his work “Moses and Monotheism” (full title: “This Man is Moses and the Monotheistic Religion”, 1939). As a Jew, raised in the strict traditions of Judaism, Freud was very interested in the deep roots of the religion and culture of his people. He suggested that Moses could subsequently be named as one of Akhenaten’s students, Osarsiph, whom the ancient Roman historian Josephus mentioned in his writings.

Akhenaten's wife was the same Nefertiti, after whom beauty salons are still named

Osarsiph was a noble Egyptian, a priest of Osiris. He became a devoted supporter of the new religion and was expelled from high society after the death of Akhenaten. Then Osarfis won the trust of the Semitic slaves and contributed to their escape from Egypt. To prove his hypothesis, Freud cites the fact that the rite of circumcision, introduced by Moses, was initially in use among noble Egyptians - it performed not so much a religious as a hygienic function (although bodily purity in the minds of the Egyptians was closely related to spiritual and intellectual purity). Further, according to Freud, the name Aten in the language of the Jews took the form Adonai (“Lord”) - one of the names of the god Yahweh.

The modern Egyptian writer Ahmed Osman, known for his revisionist conspiracy theories a la Nikolai Fomenko, generally believes that Moses and Akhenaten are one and the same person. There is also an amateur hypothesis that the princess who saved the baby Moses was Hatshepsut, daughter of Thutmose I and one of the four female Egyptian pharaohs. She ruled in the 15th century BC, 300 years before Ramses II. In this hypothesis, Moses himself is identified with Pharaoh Thutmose II, half-brother and husband of Hatshepsut (incest in the families of Egyptian pharaohs was the norm and even an obligation), or with the architect Senmut, who could be her favorite. This hypothesis is indirectly confirmed by the fact that the appearance of Thutmose II, judging by the statues and images, was more Semitic than Egyptian. However, the historical Thutmose II, although he made a number of successful military campaigns, was not seen in any attempts to lead the Semitic people out of Egypt.

Easter is past

Tenth, decisive plague: the angel of death takes the firstborn of the Egyptians and ignores the Jews

In memory of the Exodus, Jews celebrate the holiday of Passover - its name literally means “passed by”, “passed by”. This is due to the fact that during the tenth plague in Egypt, God commanded all Jews to anoint the doorposts of their houses with the blood of a sacrificial lamb - so that the punishing Lord could only enter those houses where this mark was not present and take away the firstborn of the Egyptians.

And this very night I will walk through the land of Egypt and will strike every firstborn in the land of Egypt, from man to beast, and will bring judgment on all the gods of Egypt. I am the Lord. And the blood will be a sign among you on the houses where you are, and I will see the blood and pass by you, and there will not be a destructive plague among you when I strike the land of Egypt. And let this day be memorable to you, and celebrate this feast of the Lord throughout all your generations; Celebrate it as an eternal institution. (Exodus 12:12-14)

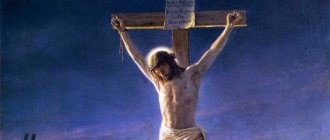

The Last Supper, described in the New Testament, was the traditional meal of Passover, which begins on the 14th day of the spring month of Nisan and continues for seven days. Jesus, being a Jew by birth and upbringing, gave it new content. And in the days of early Christianity, it was on these days that services and meals began to be held in memory of Christ’s sacrifice on the cross, which also began to be called Easter. But Christians no longer remember any Exodus of the Jews from Egypt.

Moses breaking the tablets of the Ten Commandments in despair is one of the most dramatic moments of the Exodus. This is how Rembrandt depicted him

The legend of the Exodus turned out to be such a powerful and monumental narrative that for a long time it had no other interpretations in culture other than the biblical text itself. The most logical thing was to translate this story into the language of music, art that knows how to express the inexpressible and describe the indescribable. It was the composers who were the first to take on this difficult task - in the Baroque era, which gravitated toward lush, complex structures, vivid emotions and the idea of God as an incomprehensible and overwhelmingly great supreme being.

George Handel's oratorio Israel in Egypt (1739) is a solemn and tragic story in which the main character is the suffering Jewish people (portrayed by a choir). Carl-Philipp Bach, one of the many children of Johann Sebastian Bach, diluted the monumentality with genuine human drama - in his oratorio “The Israelites in the Desert” (1769) Moses becomes the main character. Gioachino Rossini, author of the opera The Barber of Seville, created the opera Moses (1818), following the biblical canon.

But the 20th century Austrian Expressionist composer Arnold Schoenberg, in his unfinished opera “Moses and Aaron” (1930–1950), describes the conflict between two brothers: the inspired Moses and the sober-minded Aaron, who patiently explains to his brother that the people will not believe in the God he does not see that he needs miracles and signs, and finally, some images of the deity (and Yahweh categorically forbade depicting himself - the commandment “Thou shalt not make for yourself an idol” is precisely about this). The trouble is that, despite the tragic difference in worldview, Moses cannot do without his brother: Aaron is an excellent speaker, but Moses is tongue-tied and does not know how to speak in public. But in the end, Aaron dies, and the prophet has to become the leader of the people himself. At the same time, Moses tells the Jews that they will remain themselves only if they preserve their monotheism; under no circumstances should they borrow the religion of other peoples.

Often, when depicting the Exodus, artists painted heroes in clothes similar to those of their contemporaries

Jews in works on the theme of the Exodus are not always Jews themselves. In the mid-19th century, American black slaves began to identify themselves with the oppressed people - one of their spirituals (religious hymns) Go Down Moses, written based on the quote from Exodus “Let my people go!”, is most famous in the version by Louis Armstrong. And the Ukrainian poet Ivan Franko, in his poem “Moses,” writes, of course, about the difficult fate of his own people. In his version, Moses, under the influence of the demon Azazel, simply lost faith in God - and that is why he was destined only to see the Promised Land from afar, but not to enter it.

The epic personality of Moses, of course, could not help but attract romantic poets. The Frenchman Alfred de Vigny, in his poem “Moses” (1826), portrays the prophet as a superman, wise and powerful, inspiring awe instead of love, suffering under the burden of responsibility and insanely lonely. “Behind this great name hides a man of all centuries and more modern than ancient, a man of genius, exhausted from his eternal widowhood, looking with despair at how, as he rises, he is increasingly surrounded by endless and dry loneliness,” wrote poet about Moses.

If the personality of the prophet Moses could still be comprehended in literature, and the epic mood of the Exodus could still be understood in music, then only cinema could fully show all the grandiose events described in the book. The Book of Exodus seemed to be just waiting for the emergence and flourishing of Hollywood, which from the very beginning gravitated towards gigantomania.

The role of Moses in The Ten Commandments was played by Cecil de Mille's favorite actor, Charles Heston.

The very first film adaptation of the story of the flight from Egypt revolutionized cinema and is still one of the ten most beloved films by Americans. “The Ten Commandments” was filmed in 1923 and remade in 1956 by Cecil de Mille, one of the first directors of overtly commercial cinema, blockbusters in the modern sense. He loved pomp and luxury, stories with morals and crowded epic scenes with special effects. In addition, he was a believing Christian and a man of conservative views, so he considered the production of films based on biblical stories to be in some way his duty. In The Ten Commandments, double-layer (combined) filming was used for the first time, which especially impressed viewers in the scene with the Jews crossing the Red Sea.

In 1959, three years after the appearance of The Ten Commandments, another biblical epic, Ben-Hur, conquered movie screens around the world. Its action takes place in the time of Jesus Christ, and does not focus on the events of the Bible - the plot centers on the fate of a person against the backdrop of the birth of Christianity. But the ideas in the two paintings are similar - a reflection on the role of the individual in history, the nature of faith and the spiritual power of man. “The Ten Commandments” and “Ben-Hur”, which won 11 Oscars, marked the heyday of the Hollywood “peplum” genre - large-scale historical cinema in the settings of antiquity or the Ancient World.

Burt Lancaster (top) and Ben Kingsley (bottom) as Moses

“The Ten Commandments” in the 1956 version lasted 220 minutes - almost 4 hours. The events of Exodus are indeed very difficult to squeeze into less time, so the ideal format for them was a mini-series for TV. One of the most famous TV series was released in 1974 - in “Moses” (the original series was called Moses The Lawgiver, “Moses the Lawgiver”), the main role was played by the eminent actor Burt Lancaster, who had the widest range of roles available. His Moses turned out not to be an epic, terrifying figure, but a vulnerable, doubtful, lonely and at the same time strong and determined person - but a man, not a demigod.

It was Lancaster’s performance that the magnificent Ben Kingsley, who played the main character in the television film “Prophet Moses: The Liberator Leader,” was guided by. Some film critics call Kingsley the best screen Moses to date.

No popular topic can be considered fully covered unless it has been made into a parody and a Disney cartoon. The parody film All About Moses (1980) is a blatant imitation of Monty Python's Life of Brian. He talks about a man named Herschel, who, like Moses, received instructions from God, but did not know what to do with them, so he did not go down in history. This film also depicts other biblical stories - about Lot and his wife, about David and Goliath. However, the humor here is not nearly as subtle as that of Monty Python: the characters' faces are not burdened with intelligence, and most of the jokes do not rise above the waist. It's no surprise that critics tore this film to shreds.

“The Prince of Egypt” is inferior to Disney animation in terms of the quality of drawing, but not in the brightness and emotionality of the plot

As for the cartoon, it was not made by the Disney studio, but by their main competitors DreamWorks - “The Prince of Egypt” (1998) marked the birth of this studio as a producer of beautiful feature-length cartoons. The plot of the cartoon differs from the biblical one in minor details. It also focuses more on Moses' personal relationships with his adoptive and birth families, as well as with his wife Zipporah. "The Prince of Egypt" does not cover the entire Book of Exodus - it focuses on the story of Moses' self-determination as the leader of the Jewish people and ends with receiving divine commandments on Mount Sinai. Moses is voiced by Val Kilmer, who also plays God.

The musical leitmotif of the film was the emotional, tender and at the same time solemn song When You Believe, for which the cartoon received its only Oscar. In the film, she is performed by Zipporah (Michelle Pfeiffer) and Miriam (voiced by Sandra Bullock, but since the actress cannot sing, the vocal part belongs to Sally Dworsky), and during the end credits - pop stars Whitney Houston and Mariah Carey.

At the beginning of the 21st century, the peplum genre returned to the big screens, largely through the efforts of Ridley Scott with his Gladiator. Who else, if not him, should have rewritten the story of Moses? The film “Exodus: Kings and Gods,” which was released on our screens at the beginning of 2014, did not impress critics with its new interpretation, but at least it provided an extraordinary spectacle - with large-scale battle scenes and spectacular images of “the executions of Egypt.” One of the roles - the Jewish sage Navin - was played by the same Ben Kingsley.

Notes

Balaam Bilyam Job Job Abraham Abraham Sarah Sarah Isaac Isaac Jacob Jacob Moses Moshe Aaron Aaron Miriam Miriam Joshua Joshua bin Nun Phinehas Pinchas Anna Hannah Samuel Shmuel David David Solomon Shlomo Gad Gad Nathan Nathan Ahijah the Shilohite Ahijah HaShiloni Jeremiah Yirmeyahu Isaiah Yeshayahu Daniil Daniel Minor prophets: Habakkuk Havakkuk Avdiy Ovadya Haggai Haggai Amos Amos Zechariah Zechariah Joel Yoel Jonah Jonah Malachi Malachi Micah Micah Nahum Nahum Hosea Hoshea Zephaniah Tsfania Elisha Elisha Oldama Hulda First Temple Zadok • Ahimaaz • Azariah I • Johanan • Jehoiareb • Jehoshaphat • Jehoiada • Phideas • Zedekiah • Azariah II • Hilkiah Post-Prisoners Josiah • Joachim • Eliashib • Joaidah • Johanan • Jaddui • Onias I • Simon I • Simon the Righteous • Eleazar • Manasseh • Onias II • Simon II • Onias III • Jason • Menelaus • Onias IV • Alcimus Hasmonean Dynasty Jonathan Hasmonean • Simon Hasmonean • John Hyrcanus I • Aristobulus I • Alexander Jannaeus • Hyrcanus II • Aristobulus II • Antigonus II Herodians before the Jewish revolt Hanameel the Egyptian • Aristobulus III • Jesus, son of Thabetus • Simon, son of Boethus • Joazar, son of Boethus • Eleazar, son of Boethus • Annas • Caiaphas • Theophilus, son of Ananus • Simon Kanthera, son of Boethus • Elionaeus, son of Kanthera • Ananias, son of Nedeveus • Joseph Kavi, son of Simon • Ananus, son of Ananus • Jesus, son of Damneus • Jesus, son of Gamaliel • Matthias, son of Theophilus • Phannias, son of Samuel

Exodus: Gods and Cylons

The television series “Battlestar Galactica,” or more precisely its second version from 2004–2009, with its rich mystical and religious overtones, can be viewed as the Book of Exodus in a space opera setting.

The remnants of humanity, destroyed by intelligent Cylon robots, in search of the legendary Land are, in general, the same chosen people on the way to the Promised Land. Only he has two Moses. The first is the commander of the cruiser Galactica, William Adama, who once told people that he would lead them to Earth, although he himself did not know where it was. The second, or rather the second, is the President of the Twelve Colonies, Laura Roslin, the messiah from the Pythian Prophecy (“the dying leader will lead humanity to salvation”). As predicted, terminally ill Roslyn managed to see the Earth before dying - just like Moses.

In Christianity[edit | edit code]

A descendant of Aaron was Elizabeth (mother of John the Baptist) (Luke 1:5). The Apostle Paul says that the priesthood of Aaron is temporary, “for the law is associated with it” (Heb. 7:11), and is replaced by Jesus Christ, a priest according to the order of Melchizedek. In Orthodoxy, Aaron is remembered on the Sunday of the Holy Forefathers; a number of monthly calendars celebrate his memory on July 20, along with the day of Elijah the Prophet and a number of other Old Testament prophets. The Western memory of Aaron is July 1, the Coptic memory is March 28.

The classical iconography of Aaron developed in the 10th century - a gray-haired, long-bearded old man, in priestly vestments, with a rod and censer (or casket) in his hands. The image of Aaron is in the altar part of the Kyiv Sophia; it is written in the prophetic row of the iconostasis.

Table: matches for the name Aaron

| Planet | Mars |

| Element | Water |

| Zodiac sign | Scorpio, Aries |

| Color | all shades of red |

| Number | 6 |

| Animal | Dog, wolf |

| Bird | Crow |

| Plant | Nettle |

| Tree | Red tree |

| Metal | Nickel |

| Stone | Jasper, carnelian, amethyst |

| Day of the week | Tuesday |

| Favorable month | January |

| Season | Winter |

| Significant years in life | 16, 32, 46, 75 |

Name forms

Shortened versions of the name Aaron: Ron, Ara, Ari, Rona.

Affectionate addresses to Aaron: Aaronchik, Ronchik, Aaronushka, Aaronka.

If you want to compose a poem for Aaron, you can apply the following rhymes to his name: gramophone, microphone, rubicon, region, tape recorder, cupid, pharaoh, chanson, marathon, companion, attraction, cologne.

Related nominal forms: Aron, Harun.

Church version of the name: Aaron.

The patronymics that Aaron's heirs will bear: Aaronovna, Aaronovich.

In the passport the name Aaron will be written as AARON

The spelling of the name Aaron according to the latest transliteration rules is AARON.

Which middle names are more suitable for the name Aaron: Andreevich, Borisovich, Viktorovich, Egorovich, Igorevich, Ilyich, Markovich, Olegovich, Renatovich, Eldarovich, Yuryevich, Yanovich.

Nicknames for registration on various Internet resources: Aaron, Ron, Aharon, Ara.

Table: the name Aaron in foreign languages

| Language | Writing | Transliteration |

| English | Aaron | Aaron |

| Arab | هارون | Harun |

| Armenian | Ահարոն | Aharon |

| Hungarian | Aaron | Aron |

| Greek | Ααρων | Aaron |

| Irish | Aaron | Aron |

| Spanish | Aaron | Aaron |

| Italian | Aronne | Aronne |

| Chinese | 亞倫 | Aaron |

| Korean | 에런 | Aaron |

| Latvian | Ārons | Ārons |

| Lithuanian | Aaronas | Aaronas |

| German | Aaron | Aaron |

| Dutch | Aaron | Aaron |

| Portuguese | Arão | Aaro |

| Romanian | Aron | Aron |

| Urdu | آرون | Aaron |

| Esperanto | Arono | Arono |

| Japanese | アーロン | Aaron |