Why you can't portray God the Father

Such champions of the veneration of icons as St. John of Damascus and St. Theodore the Studite argued that the icon of God cannot be painted, since we do not see Him, unlike God the Son - Jesus Christ, Who had two hypostases - human and divine, and the saints who were people. As John says (1:18), “No one has ever seen God.”

The Holy Fathers rejected the icons of the Lord, since they are anthropomorphic, that is, created in the image and likeness of man, the image of God the Father. Theologians define God the Father as the first, initial and causal hypostasis of the Holy Trinity.

Historical reference

Hosts - one of the names of the Most High God, mentioned in the Holy Scriptures, is of Hebrew origin and translated means “army” (that is, the Lord who created the army).

God of Hosts. Painting by V.M. Vasnetsova

By the armies of the Creator we mean:

- defenders of Israeli lands;

- heavenly servants of God;

- the hosts of saints surrounding Him;

- stars and other similar space objects.

The phrase “Lord of Hosts” took root in the Old Testament period. As a cult name, it was used in the sanctuaries of the Hebrew city of Shiloh and was associated with the Christian Ark of the Covenant.

The doctrine of the trinity of the Holy Trinity

The Trinity of the Holy Trinity is the main Christian dogma. She is one in three persons: God the Father, God the Son (Jesus Christ) and God the Holy Spirit (depicted as a Dove), which at the same time are not fused with each other, and are inseparable manifestations of one of the essences of the Lord. This is the so-called Old Testament Trinity, the best embodiment of which in Russian icon painting was “The Trinity” by Andrei Rublev.

The famous icon of Andrei Rublev “Trinity” shows the symbolic embodiment of the Trinity in accordance with the canon. However, the “Fatherland” icon, which is often called the “New Testament Trinity,” depicts Her in a completely different way, although the three faces of the Lord should symbolize His Trinity.

Here God the Father appears in the form of a majestic old man with a gray beard, sitting on a throne; God the Son is in the form of Christ Emmanuel (Emmanuel is the designation of Jesus the youth), and on His chest, in the sphere, is a Dove, symbolizing God the Holy Spirit.

The icon “Fatherland” is of very ancient origin: the first one that has come down to us dates back to the beginning of the 11th century

It was widespread and, despite the negative attitude of the church, it can be seen in the iconostasis of many churches. As a rule, it is placed on the iconostasis in the upper rank of the forefathers, so that it seems to overshadow the entire space of the temple.

The icon “God the Father of Hosts” is extremely rare. From a formal point of view, this is like an image of the New Testament Trinity, since the medallions on the chest of the Lord also depict the two other hypostases of the Trinity (God the Son and God the Holy Spirit), but the main attention is focused on the Face of God the Father.

On the image of God the Father in the Orthodox Church

Monk Gregory (Circle)

God is completely indescribable in His being, incomprehensible in His essence and unknowable. As if dressed in the impregnable darkness of incomprehensibility. Not only are attempts to depict God in His being unthinkable, but also any definitions cannot embrace and express the essence of God; it is inaccessible to human consciousness, it is the impregnable darkness of the essence of God.

Theology itself can only be apophatic, that is, composed in negative terms: Incomprehensible, Inaccessible, Unknowable. Saint Gregory Palamas, in his defense of the Orthodox teaching about the uncreated light of Tabor, teaches us to immutably distinguish between the divine, completely unknowable essence and the Divinity in His action addressed to the created world, in His providential care for every creature. Palamas teaches to distinguish between the being of God and His divine energies-forces, radiations of grace that sustain the world.

The providential Divine action in the world is accessible to consciousness, cognizable, God addressed to the world, God extending His care, His love, His never-ending care to the world. This is wisdom that arranges everything, the light of the world that enlightens everything, the love of God that fills everything, this is the revelation of God - the manifestation of God to the world. And the world is designed by God in such a way as to perceive and accommodate this divine action, to take on this royal seal, to become entirely the royal property. The ultimate meaning and purpose of everything created is to become God's property.

The entire universe as a whole and each creation in its unique, inherent only features, conceal within themselves, as it were, some mysterious story about the Creator.

Therefore, it is incorrect to speak of God the Father as a hypostasis surrounded by complete darkness. From the very creation of the world, we see God the Father in His unceasing care for the world, in unceasing care for the human race and in unceasing communication with people, right up to His appearance, visibly and tangibly, to Abraham and Sarah in the form of one of the three Angels.

The entire Old Testament history of Israel is full of the protective care of God the Father for the chosen people. Saint Gregory the Theologian says this about Israel’s communion with God the Father: “Israel was primarily turned to God the Father.” And this closeness of the Lord of hosts to his chosen people was, first of all, closeness to the prophets. God the Father, as it were, allowed Himself to be contemplated, revealed His image with possible clarity, and perhaps one of the most complete revelations was given to the prophet Daniel in the vision of judgment, in which God the Father, as it were, spiritually outlines His image, reveals His Fatherly Face. Here is the prophetic testimony of Daniel (VII, 9, 13, 14): “I saw at last that thrones were set up, and the Ancient of Days sat down; His robe was white as snow, and the hair of His head was pure wave; His throne is like a flame of fire, His wheels are like blazing fire... I saw in the night visions, behold, with the clouds of heaven, one like the Son of Man walked, came to the Ancient of Days, and was brought to Him. And to Him was given dominion, glory and a kingdom, that all nations, nations and languages might serve Him; His dominion is an everlasting dominion, which shall not pass away, and His kingdom shall not be destroyed.” But only in the light of the Incarnation, and only in it, does the image of God the Father become possible.

In the service, in its visual part, we see a symbolic image of God the Father. At Great Vespers, while the clergy are singing “Bless the Lord, my soul... By wisdom you have created all things,” a priest, preceded by a deacon, comes out of the altar, through the royal doors, to burn incense, and walks around the temple. Here the priest signifies God the Father, who creates the universe, and is, as it were, an icon of God the Father Almighty, Creator of heaven and earth. But even in the visual part of the service, similar to the censing on “Lord, I cried,” we do not see a self-sufficient image of God the Father, but only in mutual relation to the other two hypostases or in providential care for the universe, and in this sense, the negative attitude of the Church Fathers to the image God the Father remains in force and acts in the Church, despite such a wealth of Fatherly images.

There is a prophetic definition, not rejected by the Church, that at the end of the ages a temple dedicated to God the Father will be erected. Great and glorious among all nations, this temple will be the possible fullness of the revelation of God the Father in the Church. Such completeness of the Father's appearance precedes the Last Judgment, where the Father transfers the Judgment to the Son, the Son judges the universe by the will of the Father.

Repeatedly and under different circumstances, the question arose in the Church about how the first hypostasis—God the Father—should be depicted, and whether the icon of God the Father even has a place in a number of church images. Judgments related to this issue were sometimes contradictory. And this inconsistency, it seems to us, is not accidental. This apparent duality is inherent in the very life of the “Fatherly” images.

The question of the image of God the Father already took place at the Seventh Ecumenical Council, although not as a formal discussion. And the judgments expressed by St. John of Damascus and St. Theodore the Studite, the great defenders of the veneration of icons, reject the image of God the Father. One of the main reasons for the rejection of such an image is that God the Father, depicted in human form, can create the impression or give rise to the idea of some of his primordial human-likeness. St. John of Damascus says: “We do not depict the Lord the Father because we do not see Him; if we saw Him, we would depict Him.”

From the words spoken at the Council in defense of icons, the Word of John of Thessaloniki attracts attention: “We make icons of those who were people and servants of God and wore flesh. In bodily form we do not depict any incorporeal beings. If we make icons of God, that is, our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ, then we depict Him as He was seen on earth, being among people.”

In the further development of consciousness associated with the veneration of icons, such a materialistic basis underwent significant changes. The circle of images included not only those who were people and holy servants of God and wore flesh, but also images of the Angelic world, images of Angels, which, even if they appeared in a visible image, this phenomenon could not be called “wearing flesh.” Rather, we can say that the Angels clothed themselves in a visible image as a symbol speaking of their incorporeal nature. Icons also arose that were not only pure evidence of what was unconditionally visible, but were rather filled with doctrinal and dogmatic content.

In Russia, at the Council of the Stoglavy (1551), the question of images of God the Father arose again. The council was presented for discussion with a letter drawn up by a certain clerk Viskovaty, in which this clerk questions the admissibility of images of God the Father. These doubts were apparently caused by the painting carried out in the newly built palace of Tsar Ivan the Terrible by Novgorod icon painters. Deacon Viskovaty presented a list of icons containing the image of God the Father and demanded their removal from church use. The clerk’s petition was considered separately, after the end of the meetings of the Council. Deacon Viskovaty was not recognized as right, and his petition was rejected. The decision was made in general terms, without considering each image individually. It seems that the providential significance of this decision lay in the fact that the Council, having accepted icons with very controversial iconography, preserved and accepted that icon, without which it is unthinkable to imagine the Church. This is an icon of the Holy Trinity - the Trinity of Abraham, as defined in the charter of clerk Viskovaty. This icon was included in the list of those subject to confiscation on the grounds that it contains an image of God the Father. Stoglav approved the image of the Trinity with special permission.

A few years later, the next discussion of images of God the Father took place at the Great Moscow Council (1655). This Council, in contrast to Stoglav, completely rejects the image of God the Father, making an exception only for images of the Apocalypse, where it considers the image of God the Father acceptable “for the sake of the visions there.” For the sake of the visions of God the Father in the form of the Elder, the Old One, given in Revelation.

The prohibition of the Great Moscow Council is of a warning nature. The Council's concern is determined by the fear that the human image of God the Father may inspire the idea of the human-likeness of the first Person of the Holy Trinity. The Great Moscow Council also points out the inadmissibility of the icon, which bore the name “Fatherland” and was widely distributed.

This icon is placed in the upper paternal rank of the iconostasis; it, as it were, overshadows the entire temple, and according to the iconographic plan, it strives to most fully express the paternal nature of the first Person.

This icon is very ancient in origin - the first of the surviving images dates back to the beginning of the 11th century and is preserved in the Vatican Library. This is a miniature placed in the manuscript of John Klimach (from the book by Adelheim Gaiman). Its iconography is completely established and complete and differs little from the icons of the 16th and 17th centuries that were placed on iconostases.

God the Father is depicted as an old man sitting on a throne. The appearance of the old man is majestic and calm, both hands are raised in blessing. The face is bordered by a gray, rather long and somewhat forked beard. The strands of hair are also divided in two in the middle, as is usually depicted by the Savior, and fall over the shoulders. The facial features are solemnly blissful. The vestment consists of two clothes: a tunic that falls to the ground, and a chiton - a robe similar to the one in which the Savior is depicted. All folds of the robe of God the Father are pierced with thin golden rays, asist, signifying the radiation of divine forces-energies. These rays cover the upper and lower garments of God the Father and the throne and the footstool. The head of God the Father is crowned, according to church regulations, with a halo, which is usually characteristic of the image only of God the Father or the Savior, where He is depicted in the glory of the Father, for example, on the icons of the Angel of Silence, the Old Denmi. The crown consists of two squares: one is fiery, testifying to the divinity of the Lord, the other is black-green (or blue-black), signifying the darkness of the incomprehensibility of the Divine. Such a crown, but not in the form of a halo, covering the entire image, is found on some icons of the Mother of God, for example, the Burning Bush. The Eternal Infant God the Son is depicted on the knees of God the Father. His robes, just like the Father's robes, are illuminated with golden rays - asist. The head is crowned with a crossed halo. The head of the Divine Infant rests erect, his facial features are commanding. The forehead is disproportionately large to commemorate divine omniscience. The position of the body of the seated Infant of God is as free and majestic as the position of the Father’s body. In the bowels of Emmanuel the Holy Spirit is depicted in the form of a dove. The Holy Spirit is surrounded by a blue sphere, permeated with rays emanating from Him. The Savior usually holds the sphere surrounding the dove with both hands. Sometimes the Savior is depicted with two blessing hands, like the Father.

If we return to the “Fatherland” icon and look closely at its construction, it becomes visible how this icon strives to become an icon of the Trinity and cannot completely become one. In its construction, it incorrectly matches the images of Faces. The main movement of this image is, as it were, a movement inward. God the Father in the form of an old man seems to completely absorb the images of the Son and the Holy Spirit with His majestic outlines. And the Holy Spirit, depicted in the form of a dove, is immeasurably diminished in relation to the first and second Persons. The result is an image of the Trinity, directed, as it were, into Itself, in which the dignity of the Persons is consistently diminished. Just as, for example, the image of three Persons on the cross, in which the Lord of hosts, placed at the top of the cross, blesses, and the Holy Spirit overshadows the crucified Lord with the wings, does not completely and in its entirety constitute an image of the Holy Trinity. The same can be said about the icon often placed in the iconostasis, “Seating at the right hand of the Father,” or, as it is often called, the “New Testament Trinity.”

The basis of this icon was the desire to depict the Lord Jesus Christ upon His Ascension, seated at the right hand of the Father. God the Father is usually depicted on the right side of the icon in the image of an Elder sitting on a throne, wearing royal robes, illuminated by rays, and wearing a royal crown. The Father holds an orb in his left hand. The head of God the Father is surrounded by an eight-pointed halo, inscribed in a round halo. With his right hand, God the Father usually blesses Christ, whose image is placed on the left side of the icon. The Savior, just like God the Father, has a royal crown on his head, and His head is surrounded by the usual baptized halo for the Savior. Christ's clothing is similar to the Father's clothing. Christ's face is turned to the Father and, as it were, receives a blessing from Him. At the top is placed a dove enclosed in a triangle or in a round sphere - the Holy Spirit.

In this icon we see how, due to some internal need, the “Seating at the right hand of the Father” icon turned into the “Trinity” icon, and just like the “Fatherland” icon, it did not fully express the image of the Trinity. Looking at the main outlines of this icon, you see how diminished, how inferior is the place occupied by the image of the Holy Spirit, which is the connecting principle between the images of the first and second Persons and is deprived of a completely hypostatic image. But God the Father is depicted with the same material force as Christ, and such materiality of the image, according to the judgment of many Church Fathers, can give rise to a false idea of His nature. And here we see the same impossibility of creating an immutable and completely perfect image expressing an event.

In the same way, or even more controversially, the Faces of the Holy Trinity are depicted on the star and in many other cases, for example, on the antimension. The Holy Trinity, although represented by a direct or often symbolic image of three Persons, does not find Its completely unconditional image.

Looking at the “Fatherland” icon, you see what insoluble, what painful difficulties arise in the Church in connection with the image of God the Father and especially with this image. The image of God the Father, the emergence of which was born out of some need to have such an image, does not seem to find a completely correct place for itself. If we present the images of the First Person as independent images, the measure of abstinence regarding the image of God the Father that the Church adheres to would be violated. And indeed, in the Church there was not and there is no such self-sufficient icon of God the Father, just as there is no dedication of a temple to God the Father, or a holiday in which the celebration would relate directly to the Father. And due to this dispensation, the very image of God the Father gives rise to the need not to be isolated, but to be depicted with the second and third Persons of the Holy Trinity, with the Son and the Holy Spirit...

The need to think of God the Father not in isolation is in no way false; it is the very life of the Church and will never dry up. The need that creates the image of the Trinity, emanating from the image of God the Father, does not find a completely correct solution. Such an image of the Holy Trinity is not clothed in heavenly glory, does not shine with equal unity, and becomes a mountain without a snow-white peak. Here we see some, as it seems to us, insurmountable incompleteness, which lies in the fact that the equality of the Persons of the Holy Trinity does not find its expression. In all these constructions, the third hypostasis—the hypostasis of the Holy Spirit—is not depicted personally and does not have the fullness of hypostatic dignity. In all these icons, the Holy Spirit is invariably depicted in the form of a dove, and this image cannot be equal to the image of the Father and the Son, for whose images the image of a person is taken. And therefore, all the so-conceived icons of the Trinity, not devoid of meaning in themselves, cannot become that immutable full-fledged icon, that holy seal that fully imprints the dogmatic confession of the Trinity.

The judgments of the fathers regarding the images of God the Father on icons, adopted by the Seventh Ecumenical Council, are negative. The Council recognizes that it is inappropriate to depict the Father, Whom, according to the Savior, no one saw. In the judgment of the fathers, the image of God the Father is not recognized as appropriate or even acceptable. And at the same time, the Church is full of images of the Lord of hosts. We see images of God the Father in the temple painting, in the dome of the temple, on the iconostasis in the rank of the forefathers, in many icons, such as “Epiphany”, “Fatherland”, “Trinity”, “God of Hosts in Glory, Seated on the Cherubim”. These icons are found everywhere where there is an Orthodox Church, and date back to different times. There are Byzantine images from the 11th and 12th centuries and later, and many Russian icons from different times. The 16th and 17th centuries are, apparently, particularly iconographically rich in terms of the image of God the Father.

How to explain this seemingly irreconcilable contradiction? Are all these images heretical, false, completely alien to the Church and, thus, subject to confiscation and complete destruction, or is the prohibition of images of God the Father not unconditional? One must think that the prohibitions on depicting God the Father are not ontological in nature, they are not prohibitions that, in their very essence and completely, deny the possibility of depicting God the Father, but are restrictive, ascetic measures, with the goal of imposing a fast on images of God the Father...

The first and main reason for such a restriction, it seems, was the need to firmly establish the foundation on which the veneration of icons rests. The foundation approved by the Seventh Ecumenical Council is the dogma of the Incarnation. This is the basis and affirmation of sacred images: God, who cannot be described as Deity, became describable as flesh, and since the invisible Deity became visible and tangible flesh, to that extent it can be depicted and described. The image of Christ - the imprinted hypostasis - unites two natures together, and this incarnation of God is for us the basis of the icon, like the icon of icons. Just as a stone placed at the head of a corner brings together two walls of a building, Christ, the incarnate Word, unites with Himself two unmerged hypostases: the indescribable Divinity and the describable humanity. And in this sense, the veneration of icons became possible only by Christ and through Christ, and there can be no other basis. The image of the God-man Christ became a sign of church victory and the foundation that the Savior Himself gave to the Church, imprinting His image on the ubrus. And the Fathers of the Church, who defended the veneration of icons, invariably affirm this unshakable foundation with their labors. The icon of God the Father is conceivable in the light of the icon of Christ. In the minds of believers, a split could occur, as if the image of Christ was doubled with the image of God the Father. The prohibition on depicting God the Father is reminiscent of the Old Testament prohibition on creating sacred images. Both here and there, this prohibition does not deny the possibility of images by their very essence, but imposes a ban on sacred images, similar to the prohibitions of fasting in relation to foods. Fasting does not essentially cancel the eating of food, but it does keep one from eating it for a while. And just as in the Old Testament the image of Cherubim in the Tabernacle of the Covenant was an exhaustion of the prohibition of sacred images, so in the New Testament Church the custom of placing images of God the Father on icons, which had firmly entered into church life, had already deprived the prohibition of its immutable character, made it as if clarified, not completely impenetrable. These decrees began to resemble a curtain that does not allow light to penetrate in full force, but is not a source of complete darkness.

We see the same thing in the liturgical system. The Church does not know holidays dedicated exclusively to God the Father, but celebrates the Father, “worshipped in the Trinity” on the feast of the Transfiguration of the Lord, on Epiphany, and especially on Pentecost - the Descent of the Holy Spirit, a holiday that introduces us to the fullness of the knowledge of God: Trinity - the feast of the Descent of the Holy Spirit Spirit - is marked in worship by the position of two icons on the lectern: the icon of the Descent of the Holy Spirit on the Apostles and the icon of the Holy Trinity. This latter can be considered as the basis for icons on which God the Father is depicted.

Why do believers need an icon of God?

Jesus taught: “Be like children.” If you ask any child how he imagines God the Father, he will probably say that he is a kind (or strict, but fair) grandfather with a big white beard who sits on the clouds. If the child is already familiar with the basics of Orthodoxy, he can add that Jesus Christ is also sitting there and the Holy Spirit dove is flying (approximately like on the “Co-Throne” icon).

This, of course, is a very primitive and naive idea, but it is important for a simple person to have before him a visible image of his Heavenly Father, who sees through all our worldly affairs and is able to protect us. But we also feel our responsibility before Him: when creating man, He endowed him with free will, so it depends only on us whether we choose the righteous path or the sinful one. And theological subtleties are inaccessible to most believers.

( 4 ratings, average: 4.00 out of 5)

Depicting God: Icons of Jesus Christ

The icon of Christ occupies the central place of any iconostasis, but it turns out that there are not many options for its writing. What this restraint is connected with, how the first image of Christ appeared and what the iconoclasts argued about, art historian Irina YAZYKOVA, head of the department of Christian culture at the Biblical Theological Institute of St. Andrew the Apostle, and author of books on the theology of the Russian icon, told the NS correspondent.

Angel “Good Silence”, Savior “Good Silence”. “An even more incomprehensible image,” says Irina Yazykova, “is Christ, depicted as an angel. Angela Sofia. This can be interpreted as one of the pre-hypostatic images of Christ. That is, before His incarnation. However, the image is so complex that even the heads of the Council said that such icons should not be painted. The icon itself must explain the faith, but here we have to explain the icon. Therefore, the Ecumenical Councils did not encourage such icons. Nevertheless, in the 16th century they became widespread and popular."

How to portray God? And is it possible? These questions were asked by theologians until the 8th century. The disagreements were so significant that they led to fierce disputes between iconoclasts and icon worshipers. Rejecting icons of Christ, the iconoclasts referred to the Old Testament commandment, which prohibited the depiction of God. And icon venerators, on the contrary, asserted the right to depict Christ as the Second Person of the Holy Trinity, as God who came in the flesh, because it is said in the Gospel that “the Word became flesh and dwelt among us, full of grace and truth; and we have seen His glory, glory as of the only begotten of the Father” (John 1:14). The disputes ended with the victory of the defenders of icon veneration in 787 at the Seventh Ecumenical Council. But they also emphasized that the icon depicts only the human nature of Christ, while His Divine nature still remains indescribable.

“The first icons of Christ appeared shortly before the iconoclastic disputes,” says art critic Irina Yazykova . — One of these icons, preserved in the Sinai monastery of St. Catherine, is the image of Christ Pantocrator, painted in the late antique painting technique of encaustic. Despite the unusual (from the point of view of classical iconography) realism of painting, this iconographic type looks quite established, and the physiognomic features found here will then be stable for many centuries, until the 20th century. Early images of Jesus Christ can also include the image of the Savior in the composition “Transfiguration” from the same monastery (VI century), the image of Christ Coming on the clouds from the Church of Saints Cosmas and Damian in Rome (VI – VII centuries), the half-length image of Pantocrator from Church of Santa Maria in Castelseprio (7th – 8th centuries). All of them are quite close to each other and indicate that in the 5th – 6th centuries the image of Jesus Christ in church art had already been formed.

Appearance of Christ

But how was Christ depicted before the 5th century, in apostolic times, since the apostles probably remembered exactly what He looked like?

“During the times of the first Christians, who were in times of persecution of the Church, symbolic images prevailed, not claiming realism and authenticity,” says Irina Yazykova, “so that their sacred meaning, understandable to initiates, remained inaccessible to external people located outside the Christian community.”

The symbol of Christ often became the image of a fish. The word ΙΧΘΥΣ (Greek for “fish”) can be read as an abbreviation: Ἰησοὺς Χριστὸς Θε o ὺ῾Υιὸς Σωτήρ (Jesus Christ the Son of God the Savior). The symbol of Christ was also the image of a pelican, since it was believed that in the blood of this bird there is an antidote to snake bites and in the event of a snake attack, it, tearing its chest, feeds the children with its flesh in order to save them, which is an analogy of the Eucharistic Sacrifice of Christ. Later, images of Christ appear in the form of a young man with a lamb on his shoulders; a mosaic with a similar plot, “Christ the Good Shepherd,” for example, decorates the mausoleum of Gala Placidia in Rome (5th century).

“It was a covert sermon of Christians of the first centuries,” explains Irina Yazykova. - But at the Fifth-Sixth Council of Trullo (691-692) they decided to abandon such symbolic images, since they often misled yesterday’s pagans. It was decided to depict Christ openly in the human form in which He was incarnate. True, it turned out that, except for the icons of the 5th century, no, even verbal, descriptions of Christ’s appearance were preserved. The Gospel is silent about this.

There were heated debates around the appearance of Jesus Christ. Some said that the psalms say that He is “more beautiful than the sons of men” (Ps. 44: 3), and they wrote Christ as a beautiful youth, like the Greek gods; while others, on the contrary, wrote Christ as emphatically ugly, referring to the prophecy of Isaiah: “... we saw Him, and there was no appearance in Him that would attract us to Him. He was despised and despised before men, a man of sorrows and acquainted with pain, and we turned our faces away from Him” (Isa. 53: 2-3).

But over the years, a single historical type has developed, created according to the principle of the golden ratio: harmonious proportions of the face with large eyes, a straight thin nose, dark, but not black hair, shoulder-length (as men wore in both Judea and Greece), with a slight beard. Although in different countries this image (art historians call it Greco-Semitic) changes somewhat: for example, the Ethiopians depict Him as dark-skinned, the Chinese as narrow-eyed, and in Rublev’s time in Rus' Christ was given Slavic features - light brown hair, light eyes. However, despite all the differences, Christ in the icon can always be recognized.

Shroud

All conversations about the prototype one way or another lead to the Image of the Savior Not Made by Hands, the icon of icons.

“Its very name already contains the concept of any icon, in which an important place is always given to what lies beyond the boundaries of human creativity,” says Irina Yazykova. — The miraculous image contains faith in the Incarnation, real evidence of this incarnation. I believe that the invisible God becomes visible. It is no coincidence that the fathers of the Seventh Ecumenical Council said that icons are evidence that Christ was not ghostly, but truly incarnate.

In legend, two versions of the origin of the miraculous image have been preserved (however, both can be traced only from the 6th century): one of them was widespread in the West, the other in the East. The first tells about the righteous woman Veronica, who, out of a feeling of compassion, wiped the Face of the Savior with her handkerchief when He carried the Cross to Calvary. And miraculously, the Face of Christ was imprinted on the fabric.

The second story tells about King Abgar, who fell ill with leprosy. Christ handed the king a canvas on which His features were imprinted, and the king was healed by venerating the miraculous image. Later, another miracle happened: to protect it from enemies, the shrine received from Christ was walled up in the wall, but the image of the Savior appeared on the stone. In iconography, especially Russian, two types of the Image Not Made by Hands were common: “The Savior on the ubrus,” that is, on a piece of cloth, and “The Savior on the chrepii,” that is, on a tile or stone.

“Both stories probably go back to the Shroud of Turin,” says Irina Yazykova, “a fabric on which not only the Face, but also the Body of our Lord Jesus Christ was truly imprinted in a miraculous way. The history of the Shroud is full of mysteries, but what is important for us is that it is the prototype of the iconographic scheme (and idea) of the Savior Not Made by Hands - the very first and main icon.

Christ Pantocrator

The second, very common type of icon of Jesus Christ is the image of Christ Pantocrator (Almighty), creating the Universe, holding everything in His hand.

“In this iconography,” explains Irina Yazykova, “it is no longer the dogma of the Incarnation and not the mystery of Christ’s incarnation that is expressed, but the idea of Christ’s presence on earth as the God-man.” Therefore, Christ is depicted in red and blue robes. This is a symbol of dual nature: red clothing is human nature, and blue (heavenly) is Divine.

There are three variants of this iconography: a full-length depiction of the figure of Christ, on a throne, and half-length. The most common is the waistband.

“Usually such an image was placed in the iconostasis near the Royal Doors,” says Irina Yazykova, “Christ introduces the worshiper into the Kingdom of God.” “I am the door: whoever enters through Me will be saved...” (John 10:9). Usually on such an icon the Savior is depicted with a closed Gospel, since, approaching the gates, we are only approaching the mystery that will be revealed in its entirety on the last day, on the day of Judgment, when “everything secret will be revealed” and will be removed from the Book of Life seal, and the Word will judge the world. But this principle is not always observed; sometimes icons of Christ Pantocrator are painted in the iconostasis with an open Gospel, although usually this type of iconography is more used in small icons - prayer or cell icons.

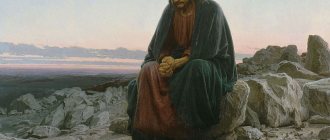

The manifestation of God's glory

“The Savior in Power” - the very name of this iconographic image reflects the theological concept of the icon - the appearance of Jesus Christ in power and glory at the end of time. In this icon, Christ is seated as the King of Kings - the iconography shows the Second Coming. Usually this image is used as the central one in the composition of the temple iconostasis. It is based on the appearance of the Lord to the prophet Ezekiel: “... and above the likeness of the throne was the likeness of a man. And I saw, as it were, flaming metal, as if the appearance of fire inside it was around; from the sight of his loins and above, and from the sight of his loins and below, I saw a kind of fire, and a radiance was around Him. In the same form as a rainbow appears on the clouds during rain, this is the appearance of this radiance all around” (Ezek. 1: 26-28).

The glory of God, seen by the prophet, is conveyed on the icon by symbolic figures. Christ, seated on the throne, is depicted against the background of a red square, on which a blue circle (oval, mandorla) and a red rhombus are successively superimposed.

“The whole composition is built on the combination of these two primary colors, red and blue,” says Irina Yazykova. - They symbolize the union in Christ - mercy and truth, His divine and human nature, unknowability and incarnation.

The red bottom square means earth. The Gospel of the Kingdom is preached to the four corners of the earth, and the symbols of the evangelists are depicted in the four corners of the square: the angel symbolizes the Evangelist Matthew, the calf symbolizes Luke, the lion symbolizes Mark, and the eagle symbolizes John. The next figure - a blue circle - means the celestial sphere, the world of ethereal forces or angelic ranks, as Dionysius the Areopagite calls them. Everything that is depicted around the figure of Christ and even the throne itself are images of various heavenly powers.

The figure of Christ Himself is surrounded by a red diamond. In contrast to the “lower” square, also red, this “upper” diamond signifies the fire coming from heaven, the fiery nature of the Divine - “for the Lord your God is a consuming fire” (Deut. 4:24). God speaks to the worshiper from the midst of the fire. Usually the Savior is dressed in red and blue clothes, but sometimes in gold, which denotes the radiance of His glory. With his right hand Christ blesses, with his left he holds the open Book.

- The image of the Book is both the Book of Life, in which the names of the saved are written (see Isa. 32: 32; Rev. 3: 5), and the Book of Revelation, written inside and outside, sealed with seven seals, which no one can open and read , in addition to the Lamb (see Rev. 5: 1-7), this is also the Book of the Covenant and Law (see Deut. 30: 10) - the Bible, and the Gospel itself - the Good News that the Savior brought to the world. And finally, the symbol of the Lord Jesus Christ Himself, Who is the Word of God who came into the world,” explains Irina Yazykova.

God is with us

The name Emmanuel appears in the Bible in the words of Isaiah's prophecy (Isaiah 7:14) and means "God with us." “Savior Emmanuel” is one of the most unusual images of Christ, where He is depicted as a baby or youth. Usually the Child holds a scroll in his hand, symbolizing the teaching that He brings to the world, the Good News. He is depicted as a man, but His teaching is in Him and with Him, for He is God and Savior.

“In this iconography we again see the idea of the Incarnation,” explains Irina Yazykova, “Almighty God has diminished to a meek, defenseless Baby.” And although it is probably more natural and understandable to stand in prayer before the icon of the Savior Not Made by Hands or Christ Pantocrator, the image of “Savior Emmanuel” expresses a deep theological idea.

The main types of iconography of the Savior are exhausted by this. Icons of Christ are closer to dogma than all other icons. They are stricter, closer to faith itself, and there is no room for imagination in them. There are also later hymnographic, complex and abstruse images, such as the “Waking Eye,” for example, or “Good Silence,” but their appearance only indicates borrowings from other cultures, in particular from Western Europe. These borrowings were not always successful, meaningful and justified.

Orthodox ascetic practice gives a special place to the icon of Christ, so that a person is led from the visible to the invisible not by his own imagination and empty dreams, but by the Word of God, “for the sake of the weakness of our understanding” (St. John of Damascus) clothed in an image. Metropolitan Philaret of Moscow wrote about it this way: “So that in search of the presence of God the mind does not fall into chimerical ideas, so that thoughts are focused and protected from distraction, the holy image of God, who appeared in the flesh, is presented simultaneously to the sensual gaze and spiritual contemplation and collects thoughts and feelings, external and internal, in a single contemplation of the Divine."

Ekaterina STEPANOVA