Modern diptych of Orthodox churches

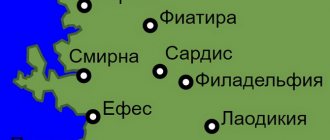

| Place | Name | Autocephaly | Primate | Believers | Official site |

| 1 | Constantinople | 381 | Archbishop, Ecumenical Patriarch | 7 million | www.patriarchate.org |

| 2 | Alexandria | I century | Pope, Patriarch | 1 million | www.patriarchateofalexandria.com |

| 3 | Antioch | I century | Patriarch | 1.5 million | www.antiochpatriarchate.org |

| 4 | Jerusalem | I century, 325 | Patriarch | 156 thousand | www.jerusalem-patriarchate.info |

| 5 | Russian | 1448 | Patriarch | 100 million | www.patriarchia.ru |

| 6 | Georgian | 457-19th century; 1917 | Catholicos - Patriarch | 10 million | patriarchate.ge |

| 7 | Serbian | 1219,1879 | Patriarch | 8 million | www.spc.rs |

| 8 | Romanian | 1885 | Patriarch | 20 million | www.patriarhia.ro |

| 9 | Bulgarian | 919, 1872 | Patriarch | 8 million | www.bg-patriarshia.bg |

| 10 | Cyprus | I century, 1947 | Archbishop | 500 thousand | www.churchofcyprus.org.cy |

| 11 | Hellasic | 1850 | Archbishop | 10 million | www.ecclesia.gr |

| 12 | Albanian | 1937 | Archbishop | 500 thousand | www.orthodoxalbania.org |

| 13 | Polish | 1948 | Metropolitan | 1 million | www.orthodox.pl |

| 14 | Czechoslovakian | 1951 | Metropolitan | 74 thousand | www.pravoslavnacirkev.cz |

| 15 | American | 1970 | Archbishop | 1 million | oca.org |

An autonomous Church

is a local Church that has very broad, but not complete, independence. Usually it has independence in matters of internal governance, provided by one or another autocephalous Church, to which this Church was previously a member on a different basis. Depending on the degree of autonomy, some local Churches are also called self-governing, semi-autonomous, etc.

Autonomous Churches within the Russian Orthodox Church

:

— Japanese Orthodox Church;

— Chinese Orthodox Church,

(doesn't actually work).

Self-governing church

- a concept introduced into the normative documents of the Russian Orthodox Church in the 1990s; denotes its large territorial-canonical unit with a special status, but not an autonomous church.

Self-governing members of the Russian Orthodox Church are:

— Latvian Orthodox Church;

— Orthodox Church of Moldova;

— Estonian Orthodox Church;

— Ukrainian Orthodox Church with rights of broad autonomy;

— Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia,

in the historically established totality of its dioceses.

Exarchate

– (from the Greek έξαρχος, “head, leader”) is a large ecclesiastical region lying outside the country in which the patriarchate is located. An exarchate may include several dioceses, the bishops and archbishops of which are subordinate to the exarch.

The Exarch is subordinate to the Patriarch and the Synod, although at the same time he enjoys a certain independence.

The Russian Orthodox Church currently has a Belarusian Exarchate (“Belarusian Orthodox Church”) located on the territory of the Republic of Belarus.

Links

- [www.biblioteka3.ru/biblioteka/pravoslavnaja-bogoslovskaja-jenciklopedija/tom-4/diptihi.html Diptychs] // Orthodox Theological Encyclopedia. Volume 4. Petrograd edition. Supplement to the spiritual magazine “Strannik” for 1903.

- Archpriest Vladislav Tsypin [www.pravoslavie.ru/arhiv/46687.htm Diptych]. [www.webcitation.org/6CW7ZGuAZ Archived from the original on November 28, 2012].

- [www.bogoslov.ru/text/192554.html Diptych]. [www.webcitation.org/6CW7e6MSN Archived from the original on November 28, 2012]. // Bogoslov.ru

Excerpt characterizing the Diptych (Christianity)

Prince Andrei, like all people who grew up in the world, loved to meet in the world that which did not have a common secular imprint on it. And such was Natasha, with her surprise, joy and timidity and even mistakes in the French language. He treated and spoke to her especially tenderly and carefully. Sitting next to her, talking with her about the simplest and most insignificant subjects, Prince Andrei admired the joyful sparkle of her eyes and smile, which related not to the speeches spoken, but to her inner happiness. While Natasha was being chosen and she stood up with a smile and danced around the hall, Prince Andrei especially admired her timid grace. In the middle of the cotillion, Natasha, having completed her figure, still breathing heavily, approached her place. The new gentleman invited her again. She was tired and out of breath, and apparently thought of refusing, but immediately again cheerfully raised her hand on the gentleman’s shoulder and smiled at Prince Andrey. “I would be glad to rest and sit with you, I’m tired; but you see how they choose me, and I’m glad about it, and I’m happy, and I love everyone, and you and I understand all this,” and that smile said a lot more. When the gentleman left her, Natasha ran across the hall to take two ladies for the figures. “If she approaches her cousin first, and then another lady, then she will be my wife,” Prince Andrei said to himself quite unexpectedly, looking at her. She approached her cousin first. “What nonsense sometimes comes to mind! thought Prince Andrey; but the only thing that is true is that this girl is so sweet, so special, that she won’t dance here for a month and get married... This is a rarity here,” he thought when Natasha, straightening the rose that had fallen back from her bodice, sat down next to him. At the end of the cotillion, the old count approached the dancers in his blue tailcoat. He invited Prince Andrei to his place and asked his daughter if she was having fun? Natasha did not answer and only smiled a smile that reproachfully said: “How could you ask about this?” - More fun than ever in my life! - she said, and Prince Andrei noticed how quickly her thin arms rose to hug her father and immediately fell. Natasha was as happy as she had never been in her life. She was at that highest level of happiness when a person becomes completely trusting and does not believe in the possibility of evil, misfortune and grief. At this ball, Pierre for the first time felt insulted by the position that his wife occupied in the highest spheres. He was gloomy and absent-minded. There was a wide crease across his forehead, and he, standing at the window, looked through his glasses, not seeing anyone. Natasha, heading to dinner, passed him. Pierre's gloomy, unhappy face struck her. She stopped in front of him. She wanted to help him, to convey to him the excess of her happiness. “How fun, Count,” she said, “isn’t it?” Pierre smiled absently, obviously not understanding what was being said to him. “Yes, I’m very glad,” he said. “How can they be unhappy with something,” Natasha thought. Especially someone as good as this Bezukhov?” In Natasha’s eyes, everyone at the ball were equally kind, sweet, wonderful people who loved each other: no one could offend each other, and therefore everyone should be happy. The next day, Prince Andrei remembered yesterday's ball, but did not dwell on it for long. “Yes, it was a very brilliant ball. And also... yes, Rostova is very nice. There is something fresh, special, not St. Petersburg, that distinguishes her.” That's all he thought about yesterday's ball, and after drinking tea, he sat down to work. But from fatigue or insomnia (the day was not a good one for studying, and Prince Andrei could not do anything), he kept criticizing his own work, as often happened to him, and was glad when he heard that someone had arrived. The visitor was Bitsky, who served on various commissions, visited all the societies of St. Petersburg, a passionate admirer of new ideas and Speransky and a concerned messenger of St. Petersburg, one of those people who choose a direction like a dress - according to fashion, but who for this reason seem to be the most ardent partisans of directions . He worriedly, barely having time to take off his hat, ran to Prince Andrei and immediately began to speak. He had just learned the details of the meeting of the State Council this morning, opened by the sovereign, and was talking about it with delight. The sovereign's speech was extraordinary. It was one of those speeches that are given only by constitutional monarchs. “The Emperor directly said that the council and the senate are state estates; he said that government should not be based on arbitrariness, but on solid principles. The Emperor said that finances should be transformed and reports should be made public,” said Bitsky, emphasizing well-known words and significantly opening his eyes. “Yes, the current event is an era, the greatest era in our history,” he concluded. Prince Andrei listened to the story about the opening of the State Council, which he expected with such impatience and to which he attributed such importance, and was surprised that this event, now that it had happened, not only did not touch him, but seemed to him more than insignificant. He listened to Bitsky's enthusiastic story with quiet mockery. The simplest thought came to his mind: “What does it matter to me and Bitsky, what do we care about what the sovereign was pleased to say in council! Can all this make me happier and better?” And this simple reasoning suddenly destroyed for Prince Andrei all the previous interest in the transformations being carried out. On the same day, Prince Andrei was supposed to dine at Speransky’s “en petit comite,” [in a small meeting], as the owner told him, inviting him. This dinner in the family and friendly circle of a man whom he admired so much had previously greatly interested Prince Andrei, especially since until now he had not seen Speransky in his home life; but now he didn’t want to go. At the appointed hour of lunch, however, Prince Andrei was already entering Speransky’s own small house near the Tauride Garden. In the parquet dining room of a small house, distinguished by its extraordinary cleanliness (reminiscent of monastic purity), Prince Andrei, who was somewhat late, already found at five o’clock the entire company of this petit comite, Speransky’s intimate acquaintances, gathered. There were no ladies except Speransky's little daughter (with a long face similar to her father) and her governess. The guests were Gervais, Magnitsky and Stolypin. From the hallway, Prince Andrei heard loud voices and clear, clear laughter - laughter similar to the one they laugh on stage. Someone in a voice similar to Speransky’s voice distinctly chimed: ha... ha... ha... Prince Andrei had never heard Speransky’s laughter, and this ringing, subtle laughter of a statesman strangely struck him. Prince Andrei entered the dining room. The whole company stood between two windows at a small table with snacks. Speransky, in a gray tailcoat with a star, obviously still wearing the white vest and high white tie he wore at the famous meeting of the State Council, stood at the table with a cheerful face. Guests surrounded him. Magnitsky, addressing Mikhail Mikhailovich, told an anecdote. Speransky listened, laughing ahead at what Magnitsky would say. As Prince Andrei entered the room, Magnitsky’s words were again drowned out by laughter. Stolypin boomed loudly, chewing a piece of bread with cheese; Gervais hissed with a quiet laugh, and Speransky laughed subtly, distinctly. Speransky, still laughing, gave Prince Andrei his white, tender hand. “I’m very glad to see you, prince,” he said. - Just a minute... he turned to Magnitsky, interrupting his story. “We have an agreement today: dinner of pleasure, and not a word about business.” - And he turned to the narrator again, and laughed again. Prince Andrei listened to his laughter with surprise and sadness of disappointment and looked at the laughing Speransky. It was not Speransky, but another person, it seemed to Prince Andrei. Everything that had previously seemed mysterious and attractive to Prince Andrei in Speransky suddenly became clear and unattractive to him. At the table the conversation did not stop for a moment and seemed to consist of a collection of funny anecdotes. Magnitsky had not yet finished his story when someone else declared his readiness to tell something that was even funnier. The anecdotes mostly concerned, if not the official world itself, then the official persons. It seemed that in this society the insignificance of these persons was so finally decided that the only attitude towards them could only be good-naturedly comic. Speransky told how at the council this morning, when asked by a deaf dignitary about his opinion, this dignitary answered that he was of the same opinion. Gervais told a whole story about the audit, remarkable for the nonsense of all the characters. Stolypin, stuttering, intervened in the conversation and began to speak passionately about the abuses of the previous order of things, threatening to turn the conversation into a serious one. Magnitsky began to mock Stolypin’s ardor, Gervais inserted a joke and the conversation again took its previous, cheerful direction. Obviously, after work, Speransky loved to relax and have fun in a circle of friends, and all his guests, understanding his desire, tried to amuse him and have fun themselves. But this fun seemed heavy and sad to Prince Andrei. The thin sound of Speransky's voice struck him unpleasantly, and the incessant laughter, with its false note, for some reason offended the feelings of Prince Andrei. Prince Andrei did not laugh and was afraid that he would be difficult for this society. But no one noticed his inconsistency with the general mood. Everyone seemed to be having a lot of fun. Several times he wanted to enter into conversation, but each time his word was thrown out like a cork out of water; and he could not joke with them together.