Origin and life of the saint

Macarius was born in Egypt into the family of a priest. The elderly Abraham and Sarah did not hope to have children. One day an angel appeared to Abraham with the news of the birth of a son, who was destined to be the dwelling place of the Holy Spirit and live among people in angelic form. From a young age, Macarius strove to serve God, but his parents forgot about the angel’s prediction and forced him to marry.

3 days after the wedding, the wife died of fever as a virgin. Abraham and Sarah no longer insisted on their son's marriage. Macarius cared for his elderly parents and diligently attended church. After the death of his father and mother, he distributed all his property to the poor and settled in the desert, not far from the village where he lived.

His mentor was an elder monk, next to whom Macarius built a cell. All his days were spent in labor (basket weaving) and prayers. A distinctive character trait of St. Macarius was humble.

Macarius did not contradict anyone, accepting injustice as a temptation that he must overcome.

From the biography of the reverend it is known that a girl slandered him, calling him the father of her unborn child. The villagers believed her, brutally beating the saint.

Macarius did not prove his innocence. He began to give her the money he earned from selling the baskets. During the birth pangs, the girl admitted to lying. Her parents decided to repent before the saint, but Macarius did not want vain glory. He secretly left his cell and went into the Faran desert. After spending 3 years in silence, Macarius went to the founder of Egyptian monasticism, Anthony the Great.

Reverend Father Anthony had already heard about the blessed one and treated him with attention and love. Macarius became his like-minded person and supporter. After some time, Macarius left Anthony and, on his recommendation, headed to the Skete hermitage. The hermit led an ascetic lifestyle: he ate a little bread and water once a week, and slept fitfully, leaning against the wall of his cell.

Trying to avoid tempting thoughts, Macarius remained in silence, keeping prayers in his mind. Detachment from worldly goods reached such a degree that when one day the hermit noticed a thief in his cell, he helped him collect his simple belongings and load him onto a donkey.

Macarius at a young age achieved the spiritual maturity that is inherent in elders. For his wisdom and patience he was called an old man. The blessed man’s saying that an unkind word will make a kind-hearted person evil, and a good word will make a hard-hearted person good, has become popular. The fame of the ascetic spread throughout Egypt, and pilgrims flocked to him: for healing, prayer, advice.

He gained followers who built cells next to the saint’s home. 5 years passed, and 4 churches appeared in the harsh region, Macarius became a presbyter. In 374, the persecution of the Orthodox began in Egypt. The most influential monks, including Macarius, were removed to an island among the pagans in the Nile Delta. The humility and virtue of the confessors struck the minds of the pagans, and they accepted Christianity. Popular outrage forced the monks to return from exile.

MACARIUS THE GREAT

(Corpus Macarianum). I. Composition, manuscript collections and translations into ancient languages. Greek the texts came in the form of 4 collections, the so-called. "types". The first type is the most extensive, containing 64 Words (the 62nd belongs to another author). It completely includes type IV (not published separately) and partially overlaps with types II and III. Type II, the most common, contains 50 conversations, published in full; Of the additional 7 conversations, the 54th and 57th are not authentic. Manuscripts of type III include a different number of works; only those characteristic of this collection were published separately (in the edition of E. Klostermann and H. Berthold in 1961 and again, with the exception of small overlaps with type I, in 1980, with the French translation by V. Despres). In one of the 2 Arab. collections dating back to the lost Greek collection, Words not extant in ancient Greek have been preserved, they are published in a German translation by Strothmann (1975). In addition, there are selections (anthologies) from the works of the Makarievsky corpus.

The Makarievsky corpus has been preserved in numerous handwritten collections in Greek, Syriac, Coptic, and Arabic. and cargo. languages. There are also incomplete collections, which probably reflect other ancient or more complete collections of conversations. The collection of type I is represented entirely by 2 manuscripts of the 13th century. (Vat. gr. 694; Athen. Bibl. Nat. gr. 423) and several, containing only part of the conversations; collection of type II - manuscripts of the 11th-12th centuries. (Panag. 75; GIM. Syn. Greek. 320) and others later; collection of type III - manuscripts of the 11th century. (Athen. Bibl. Nat. gr. 272) and XV century. (Ath. Pantel. 129); collection of type IV - manuscript of 1045 (Paris. gr. 973) and others later. Some works have been preserved under the names M.V., St. Basil the Great, St. Ephraim the Syrian, Abba Isaiah, St. Mark the Ascetic, Simeon of Mesopotamia; the manuscripts of these works are often older than those of the direct tradition.

Main sire. the corpus has a pronounced anthological character (ed.: Strothmann. Die Syrische Überlieferung. 1981); Sinaitic manuscript of the 10th century. (Sinait. syr. 14) contains the same material as the main collections.

In Arabic. language there are 2 collections (cf.: Graf. 1944): a collection of type IV under the name M.V. (in the RKP. Vat. arab. 84, 1055, close to the RKP. Paris. gr. 973) and a collection under the name St. Simeon the Stylite (in the Vatican manuscripts (“TV”) - Vat. arab. 70 (T), 80 (V)); in Paris. arab. 149; etc.), lost in Greek except for 7 short works under the name of St. Simeon (in the RKP. Vat. gr. 2028, XI century). The second collection is found in a number of Said fragments (also represented in the Type III collection; identified in: Suciu. 2011); consists of 36 conversations, approx. 40 questions and answers and 30 short passages; may date back to an earlier collection than the main Greek ones. German translation of the Arabic version of the works of this collection, lost in Greek (the 33rd homily has survived and was also published in Syriac): Strothmann. 1975. Seven works extant in Greek (under the title τοῦ ἁγίου Συμεῶνος) and included in Arabic. collection (one of them is included in the collection of type III, 6 others - in the collection of type I; this small collection was indicated by Jehin: Géhin. 1996. P. 60-62 (description of contents based on the archival catalogue); P. 61. Not 14 (general identification of 7 passages)) appear to be fragments from lost Greek. RKP prototype. Vat. arab. 80 and retained the author's true name. The condition of the text in them is in some places better than in collections of types I, II and III (ed.: Desprez. 2015. pp. 783-795).

Cargo. the translation of the Type IV collection was carried out by Rev. Euthymius Svyatogorets (955-1028; ed.: Ninua. 1982. P. 156-198).

The most ancient surviving texts of the Makarievsky corpus reflect (taking into account discrepancies) sire. version of the Word I 48 = II 5 under the name of St. Mark of the Ascetic (Vat. syr. 122, 769), sire. transfer to the RKP. Sin. syr. 14, “Great Epistle” under the name of St. Ephraim the Syrian (according to the Russian Orthodox Church no later than the 8th century) and 7 fragments under the name of St. Simeon the Stylite. The collection of 8 letters in Greek (CPG, N 2402/2-4), attributed to “Makariy Scete”, does not belong to the Makarievsky corpus.

The division of the Makarievsky corpus into speeches-conversations (in which the author sets out his teaching), compilative series of short sayings, letters (replete with biblical quotations), question answers (more polemically pointed) are available in most collections (for the literary genres of the corpus, see: Dörries . 1941).

The main later anthologies compiled from conversations of the Makarievsky corpus include:

1. “On the preservation of the heart” (De custodia cordis; Word 1 = Opusculum I; CPG, N 2413/1; PG. 34. Col. 821-841), later revision (according to the now lost text, close to Vindob. Theol 192) hesychast anthology, which is contained in many. manuscripts of ascetic collections used in the publication of the works of Evagrius of Pontus (see: Géhin. 1994). Consists of 2 parts: 4 fragments from collection type IV (Macar. Aeg. I 1. 7. 7 - I 1. 9. 13; IV 9, 16, 21 - PG. 34. Col. 825-841; under the name of St. Mark of the Ascetic: PG. 65. Col. 1064-1069); several short fragments from collections of types I and II and 146 fragments from the epitome (partially ed.: PG. 34. Col. 821-825; ed. from French translation according to the RKP. Ath. Vatop. 57. 418r-429r: Desprez. 2015. pp. 826-832).

2. Epitome of 150 chapters (CPG, N 2413/2; Words 2-7 = Opuscula II-VII; PG. 34. Col. 841-968), anthology based on collection type IV; partially published: Desprez. 2015. pp. 751-760 (introduction and chapters 6-7, lengthy review), 895-912 (chapters 45, 62-63, 67, 74, 92, 94, 96, 134-135, 137-143, cited by St. Gregory Palama). There are lat. translations, 1st attributed to Angelo Clareno (in the RCP. Vat. Urb. lat. 521 and 2 other manuscripts, according to the best Greek text), 2nd - Pedro de Valencia (according to the RCP. Upsal. gr. 3, combining 2 best reviews; ed.: Pedro de Valencia. 2001. P. 353-420; Russian translation: Macarius of Egypt, Venerable Spiritual Conversations, Messages and Words. Serg. P. 19044. M., 1998. P. 345 -467); table of correspondences of Words 1-7 to type I: Desprez. 2015. pp. 978-980.

3. “Mosaic Collection” (name given by G. Durris), a collection of 24 Words, grouped thematically and made up of fragments of conversations, which are included in collections of types I and II. Represented by 3 manuscripts used in the publication of the “Great Message” by R. Staats and Berthold (Ibid. p. 842). The primary analysis was done by Desprez (by studying the RKP. Paris. gr. 915, XIV century, and collating excerpts of conversations from the collection of type IV; partially ed.: Desprez. 2015. pp. 844-858).

II. Place and time of writing. The Makarievsky corps was created by an ascetic who, in all likelihood, lived in the Greek-speaking region of the Roman Empire, between Edessa, Antioch and Pontus (based on the geographical and historical data found in the corps), and was the inspirer of a group of monastic communities and individual ascetics . His activities ranged from the 60s to the 90s. IV century The upper time limit (terminus ante quem) of the Makarievsky Corps can be the death of St. Gregory of Nyssa (c. 394), who “processed” the “Great Epistle” (probably one of the later works of the “corpus”) in the form of a treatise “On the purpose of life according to God and on true asceticism” (De instituto christiano). The lower time limit (terminus post quem) could be the accession to the throne of the imp. Elia Flacilla (383), wife of the emperor. Theodosius I the Great, researchers see an indication of this in one of the conversations (Macar. Aeg. III 25. 4. 5; see: Fitschen. 1998). To the events of the 2nd half. 4th century, perhaps also include: a mention of royal eunuchs exempted from military service (Macar. Aeg. III 4. 1. 3), which may be an allusion to the campaigns carried out by the eunuch Eutropius against the Huns in 397 and 398 .; message about the birth of the empress (Idem. I 14. 34 = II 42. 2), which probably means the birth of the emperor. Gauls Placidia (80s of the 4th century) and imp. Honoria (384) (Fitschen. 1998. P. 170); comparison with a city that fell into the power of a tyrant and then returned to the rightful ruler (Macar. Aeg. I 3. 4. 7-9; 61. 1. 3-4; Arabic homilia 30 in the RKP. TV), which is possible , is associated with the capture of Amida by King Shapur II (350) and its liberation by the emperor. Julian the Apostate (363) (however, the capture is attributed to the Indians and Saracens, and not to the Persians; cf.: Plested. 2004. P. 12), or with the activities of the usurper imp. Magna Maxima in the West. Mesopotamian bishops and monks, i.e. Pseudo-Macarius with close devotees, could be present at the Second Ecumenical Council (381) (Greg. Nyss. De deitate adv. Evagr. // GNO. T. 9. P. 336-338; in this Word a theme is developed that is close to the Macarius corpus - cf.: Macar. Aeg. I 16. 3. 1 = II 17. 12; see: Staats. 1967. S. 167-179). Indirect indications that the author of the Makarievsky corpus belongs to the 4th century. may also be: a confession of faith in the Holy Trinity, contained at the beginning of the “Great Message” and close to the Creed of the Second Ecumenical Council; mention of the feast of the Nativity of Christ (Macar. Aeg. II 52), attested in Cappadocia (Basil. Magn. In Christ. generat.; CPG, N 2913; the authorship of the homily is disputed, but J. Gribomont and M. Obino considered it genuine), in K-field (379-380; Greg. Nazianz. Or. 38 // PG. 36. Col. 313; see: Moreschini C. Introd. // SC. 358. P. 16-22) and in Antioch (386 ; Ioan. Chrysost. In diem Natalem // PG. 49. Col. 351; see: Lemarié. 1957; Jounel. 1983); Features of the Eucharistic rite and theology attested to c. 380 in the areas of Antioch (Desprez. 1990. P. 212-213, 221); The Christology of the Macarius Corpus is anti-Apollinarian and Alexandrian (Macar. Aeg. I 10.4), pre-Chalcedonian (Ibidem; see: Dörries. 1941. S. 166. Not. 1; Macar. Aeg. I 49 = II 4; cf.: Balthasar H.-U. La gloire et la croix. P., 1965. Vol. 1. P. 228; Dörries. 1978. S. 327. Not. 33).

III. Author's personality. The Makarievsky Corps was created, in all likelihood, by Ser. author, who was in close contact with the Greek. cultural world. Its religion he describes the calling as a consequence of the failure of life in the world (Macar. Aeg. II 32. 7-8; 45. 4). Use along with biblical and specifically sir. themes and concepts of some Platonic and Stoic themes indicates that he received a secular education (see: Stoffels. 1908. S. 57-71; however, according to M. Spanne, such Stoic themes as the subtle corporeality of the soul, the theory of mixtures, dispassion, interdependence of virtues, by this time had already been Christianized, and the vocabulary of the Macarius corpus is very far from the vocabulary of the Stoics - Spanneut. 1973. P. 148, 150, 170-175). Although he only quotes St. Scripture, however, mentions certain philosophers and makes allusions to the apocryphal “Acts” of the apostles; allegorical exegesis is given in line with Origen and the Cappadocians. In general, the creator of the Makarievsky Corps is more characterized by a calm and free approach. authors with little connection to the Greek. philosophy and expressed, in accordance with the Semitic tradition, poetically (for example, St. Ephraim the Syrian, whose symbolism is close to the figurative world of the Makarievsky corpus). The characteristic “spatial” imagery of the body also brings it closer to the sire. Christ lit-roy (for example, the idea that a person is “filled” with the Spirit or sin, which is also found in Aphraates - Aphr. Demonstr. 1. 14 and in the “Book of Degrees” - Stewart. 1991 . P. 223-232).

IV. Messalian context. From approximately 1920 to 1975, the author of the Makarievsky corpus was considered as one of the leaders of Messalianism, however, K. Stewart (Stewart. 1991) and other contemporary. researchers have introduced nuances to this issue (see the judgments of the Messalians in comparison with the texts of the Makarievsky corpus: Dunaev. 2015. P. 99-103). According to K. Fitschen (Fitschen. 1998), Adelphius (who expounded the teaching of the Messalians to St. Flavian I of Antioch, see: Theodoret. Hist. eccl. IV 11; Idem. Haer. fab. IV 11) read at least part of the Macarius corpus, however, he singled out and sharpened the Syro-Mesopotamian theme, close to its author (the rootedness of evil in man, the significance of prayer, spiritual experience). Thus, the founder of Messalianism was Adelphius, and the creator of the Macarius Corpus was the “forerunner” of this teaching, an involuntary inspirer, and not a theologian of the Messalians. Valerian of Iconium, the author of the “Ephesian list,” examined not the Macarius corpus, but the Asceticon, compiled by the Messalians on the basis of some texts of the corpus. Fitschen distinguishes the “prayermen” who form the group around Pseudo-Macarius from the Messalians (Fitschen. 1998. S. 238). The first united for the purpose of prayer (only in the “Great Epistle” and in the 21st and 48th Words of type I it is said about monks, in the 3rd conversation of type II - about 30 brothers living together) and were receptive to the teaching mentor. From about 375, when Adelphius presented himself as the interpreter of Pseudo-Macarius, certain “prayer books”, more radically minded, became proper Messalians. The teachings of the Makarievsky Corps no longer influenced them. Fichen, therefore, separates Pseudo-Macarius from the Messalians, although the spiritual experience of the former influenced the latter. Based on the analysis of the polemics and issues found in the corpus, its author and the Messalians were in communication with each other (Desprez. 1998. P. 333-337, 412). According to A.G. Dunaev, the teaching of the Makarievsky corps is incompatible with the teaching of the Messalians: a list of their views, known to St. John of Damascus, was established first at the K-Polish (426), then at the Ephesian (431) Councils through tendentious excerpts from the Makarievsky corpus, which was in circulation among the Messalians, as a summary of the ascetic book of the Messalians (Dunaev. 2015. pp. 99-113) . According to M. Plested (Plested. 2004), the Makarievsky corps does not depend on the Messalians and is part of the spiritual heritage of Orthodoxy.

V. Stages of formation. According to Dörries (1941), several can be distinguished. stages of the formation of the Makarievsky corps in accordance with internal references and development of themes. The oldest layer is the “Asceticon”, a catechism for the instruction of beginners (main questions: Macar. Aeg. I 2, 4-7 (cf.: II 6-7, 12, 16, 26-27); I 32-33 , 45 (cf. II 15); II 3). The development of the controversy allows us to distinguish 4 periods (Dörries. 1941, in the 2nd part of the book there is an analysis of each period; later Dörries discarded this hypothesis (Idem. 1978. S. 14) and presented the teaching of the Makarievsky corps in a synchronous form): 1) topic the evil hidden in man, the limits of external asceticism, the need for internal prayer (cf.: Macar. Aeg. I 8); 2) the author of the corpus seems to be already a revered teacher (cf. II 51), but with opposition arising; 3) denunciation of ascetics who are proud of their rules (I 4. 13 = III 14. 1), rationalist teachers (III 22), fruitless theological debates (III 25. 6. 2), superficial Pharisaic monks (I 64), followed by. why there is a controversy with Pseudo-Macarius (I 1. 1, 13) and persecution against him (I 6. 2. 1 = II 26. 22-23); 4) in the midst of the crisis, the “new Pharisees” justify themselves (I 40); the controversy centers around Baptism and church organization (I 33.2 = II 15.14-15; I 43.52).

VI. "The Great Message" Among the messages included in the Makarievsky corpus, the “Great Message” is the largest and most structured (the remaining messages are Macar. Aeg. I 40; II 51; III 28; Arabic homilia 10 in the RKP. TV). It represents the 1st Word of the collections of types I and IV and conversation 36 of the “Simeonian” Arabic. collections (TV). In collections of types II and III it is given in the form of a short fragment (II 40 = I 4. 1 = Word 4 in the Athen. Bibl. Nat. gr. 272).

The message is characterized by clearly defined references to St. Scripture (it contains 111 biblical quotations and 87 allusions). It was built according to a strict plan (see: Makarios-Symeon. Epistola Magna. 1984. S. 63-75). Following the prologue (chapter 1), the theological foundations of asceticism (chapters 2-5) are given: the goal of asceticism is liberation from passions with the help of the Holy Spirit (chapter 2), Christ. life must develop towards Christ's perfection (chapter 3) with the assistance of grace and human effort (chapter 4); the sublimity of this goal excludes all pride (chapter 5). In the main part of the message (chapters 6-11), the author explains how these foundations are implemented in life in Monaco. He talks about the discipline of the community (chapter 6), that love for God and prudence make it possible to avoid spiritual dangers (chapter 7), that there are brothers who can devote themselves completely to prayer (chapter 9) , and brothers serving and working (chapter 10), as well as the relationship between the two categories of brothers (chapter 11). This is followed by a summary, conclusion (chapter 12) and an appendix (chapter 13), possibly later (in the RKP. Marc. gr. 52, chapter 13 follows doxology), in which the author defends himself from the reproach, “as if we... trust in the impossible and in the superhuman,” setting ourselves the goals outlined in the Holy Scriptures. Scripture, and refutes the opinion that it is impossible to achieve the state to which Scripture encourages us, “whether we are talking about perfect purity and deliverance from passions or about the coexistence and fullness of the Holy Spirit” (13.1). Thus, the “Great Message” reflects the twofold constant attitude of the author of the Macarius Corpus: on the one hand, to lead his correspondents to the correct attitude towards Messalian aspirations, on the other, to induce internal effort and protect this attitude from possible superficial understanding.

Derris showed that the confession of the Trinitarian faith, with which the “Great Epistle” begins (1.3), is very close to that compiled at the Second Ecumenical Council: the author of the Macarius Corpus uncompromisingly confesses the deity of the Holy Spirit, acting in the soul of man, but not mixing with her. The proclamation of the divinity of the Holy Spirit at this Council may not have been without connection with the sir. asceticism and could explain the theoretical radicalization of Messalianism in Adelphius (Dörries. 1956; Idem. 1966. S. 130ff; Staats. 1979. S. 238-241). Probably, the author of the Macarius Corpus was forced to write the “Great Epistle” with the substantiation of his ascetic teachings by the fact that St. Amphilochius of Iconium began the fight against the Messalians in Cappadocia.

St. Gregory of Nyssa reproduced the “Great Epistle” in Op. “On the purpose of life according to God...”, perhaps with the aim of presenting the spiritual experience captured there to a wide educated audience in a more philosophical language, softening certain extremes (in particular, excluding the theme of the primacy of prayer, from Chapter 11 to the end of the “Great messages").

VII. Controversy reflected in the Makarievsky Corpus.

1. “External” devotees. In the 52nd Word from the collection of type I, the author speaks out against those who rely only on “carnal excuses” and who do not care about the inner spiritual man. The “Great Epistle” explains the need for internal achievement and, in connection with this, refutes the accusation of requiring impossible efforts from a person (Macar. Aeg. I 1. 13). Particularly deserving of censure are the “intellectuals” who deny the possibility for the spiritual man to obtain knowledge through grace and allow revelation only through rational knowledge or through meditation on Scripture and its interpretation. The most common polemics are against those who teach without spiritual experience or discuss the Holy Scriptures. Scripture, not having the Holy Spirit in itself (III 22. 1; Arabic homilies 12 and 23 in the RKP. TV). Vainglorious ascetics who pride themselves on strictly following the rules are often exposed: a truly spiritual person wants to remain hidden from people; better is less strict asceticism, but more humble (III 21. 3. 2), internal; Moreover, the result is possible only under the influence of grace.

According to the author of the Makarievsky corpus, “external” ascetics are characterized by a denial of the deep impact of evil on a person: evil, in their opinion, approaches only from the outside (I 32.3.1 = II 15.13), and a person can reject it if he wants; after baptism, evil no longer has a place in the human heart (I 4. 27. 2 = II 16. 10). “External” ascetics, the “new Pharisees,” clean only the surface of the cup and dish (cf. Mt 23:25), while spiritual people take care of the subjugation of even internal passions. These ascetics (an early variety of semi-Pelagians) assert that “the Lord requires only obvious fruits, but God Himself does the secret things” (Macar. Aeg. II 3. 3b); that it is enough to renounce property and marriage. This position brings the “external” ascetics closer to those brothers who retreat before the difficulties of prayer (I 4.4 = II 40.6).

2. "Determinists". Representatives of the opposite position deny free will. “Some heretics claim that matter is without beginning and that it is the root, the radical force, and is equivalent to God” (I 46. 1. 1 = II 16. 1). This "heresy" combines the ancient Greek belief in the eternity of matter with the Manichaean assertion of a second principle along with God; further ideas are refuted, which claim that evil is substantial (ἐνυπόστατον) (I 46. 1. 2). Perhaps this substantial evil is identical to matter - a principle hostile to God. Two other opinions are close to this: “Some... claim that “shameful passions” are natural and came from God (Rom. 1.26)” (Macar. Aeg. I 40.1.2). The “false brethren” mislead the correspondents of the author of the Makarievsky corpus, telling them that “a person cannot do anything good unless the grace of God forces him by force” (Arabic homilies 10 in RKP. TV).

Other representatives of this trend are characterized by a denial of freedom: “If a person has died spiritually, he can no longer do anything good” (III 27. 3). “The opposing force is stronger, and vice completely reigns over man.” To this view, the author of the Makarievsky corpus responds: “You accuse God of injustice, who condemns humanity” for sin (II 3. 6). “Determinists” also attribute to God an arbitrary choice between the chosen and the rejected: “Some bring injustice to God, unreasonably limiting [His] election and foreknowledge, as if He chooses the one whom he wants to save, and whom he wants to destroy, leaving him to his reckless desires” ( I 31.5.4). However, predestination is nothing more than the result of divine foreknowledge: God initially foreknew those who would love Him, so He justly chose them. These varied opinions ultimately lead to fatalism and moral permissiveness. Contrary to such misconceptions, the author of the Makarievsky corpus recalls the existence of freedom of choice and the goodness of creation.

3. Messalians. The author of the Makarievsky corpus probably communicated with certain ascetics, very similar to the Messalians, close to his students or addressees. So, according to him, some ascetics pray, emitting “inappropriate and disorderly cries” under the strong influence of repentance, internal suffering and, possibly, tension, trying to achieve the effect of grace. These people “pray with agitation and confusion, so that they lead into temptation those who hear them.” Regardless of whether their prayer is sincere or counterfeit, they compromise asceticism (II 51.3). The author of the Makarievsky corpus contrasts the words of St. Apostle with counterfeit prayer. Paul: “God is not a God of disorder, but of peace” (1 Cor 14:33).

Other “prayers” (i.e. Messalians in the proper sense of the word) denied the need for asceticism if there is no reward in the form of the experience of grace: they “seek the Kingdom by prayer and do not avoid voluptuousness” (Macar. Aeg. I 38.2.5). In their opinion, “if someone fulfills all the commandments and stands, but does not acquire grace in this age, he will not receive any benefit” (I 2.4.1). Some considered serving the brothers burdensome (I 4.30.12). A similar idea arose after. messalian premise about the possible and necessary experience of receiving grace. The author of the Makarievsky Corpus teaches those who do not see this experience in themselves not to despair.

Many ascetics believed that transformation under the influence of grace occurs suddenly and completely. Some referred to the Gospel of John (John 5.24; cf. 1 John 3.14): “After [receiving] grace, they “passed from death to life”” (Macar. Aeg. I 6.7 = II 27. 13), others - on the Epistle to the Galatians (Gal 3.27): “You have put on Christ,” and following. They argued that “he who has acquired the grace of God always remains unchanged and cannot change” (Arabic homilies 10 in the RKP. TV). Therefore, some believed that they had acquired grace and acquired dispassion. After receiving grace, in their opinion, the soul is already freed from worries (Macar. Aeg. I 16.2.3 = II 7.8); they were proud of it and expressed satisfaction by saying: “We have achieved”; “We have had enough, we have no more need” (I 7. 7. 4 = II 26. 17). The author of the Makarievsky corpus considers such people to be reckless ignoramuses (I 34. 10), ridiculing them: “You are perfect, enough is enough for you, you have already become rich, you no longer need knowledge, you are blessed” (I 7. 12. 2 = II 27. 6 ).

Other “inexperienced” brothers were surprised that evil still affected them even after receiving grace (I 46. 1. 5 = II 6. 3). They believed that “there is no longer a place for lust in Christianity” (II 38.4). Trials and temptations opened their eyes to the superficial nature of psychological “transformation”: the vice still remains; if he stops acting, it is only to make him forget about himself (I 46. 1. 5 = II 16. 3).

Finally, in the Makarievsky Corps about ascetics (sometimes after receiving great spiritual gifts). Fall includes pride and condemnation of one's neighbor (I 7. 12. 2 = II 27. 6). Separation from the fraternity also leads to great unrest. Some confessors of the faith have reached the point of sinful depravity or apostasy. Probably, speaking precisely against Messalian simplifications (grace replaces sin), the author of the Macarius Corpus speaks of the coexistence in man of evil and grace, presented as two “spirits” (I 16. 1. 8 = II 17. 4).

Miracles

People flocked from all over Egypt to the Skete desert to see Macarius the Great, hoping for his help in illness and sorrow. Macarius set up a hotel for the sick.

Every day the monk healed one sick person with holy oil, keeping the rest in the monastery in order to cleanse not only the body, but also the soul from illness.

The saint, in order to sometimes remain alone with God, made a hidden room under his cell. Here Macarius indulged in prayer and contemplation of God.

The Monk Macarius was at the repose of Saint Anthony the Great. The saint inherited a staff, on which the elder leaned when walking. It doubled his spiritual power. The saint's mercy and humility knew no bounds. Macarius offered prayers to the Lord for the righteous and sinners.

Blessed Macarius reached such spiritual heights that at the age of 40 God endowed him with the gift of miracles. Once, to prove to the heretic that the human soul is immortal, Macarius resurrected the dead. The heretic appeared in the desert and began to proclaim to the disciples of Macarius that there was no resurrection of the dead. He was witty and sarcastic, and the monastic brethren doubted the truth of the Christian faith.

Macarius did not argue with the tempter, but suggested going to the monastic cemetery and making sure of the resurrection. Together with the heretic and the monks, the monk came to the cemetery. After a long prayer, Macarius cried out to the Lord to revive the recently deceased monk. The monk called out the name of the recently buried monk, and everyone heard the answering exclamation. The monks dug up the grave and brought out their revived brother. The frightened heretic disappeared into the desert.

Twice more did the Monk Macarius perform short-term resurrections of the dead: to help an unfortunate widow repay her husband’s debt; justify the innocently convicted.

The prayers of Saint Macarius helped against witchcraft and in driving out demons. One wizard, at the request of a wicked man who wanted to persuade a beautiful married woman to cheat, cast a spell that made her seem like a horse to everyone. Three days later, Macarius the Great, at the request of her husband, freed the woman from magical deception by dousing her with holy water.

In a similar way, Macarius delivered from evil spells a girl turned into a donkey, which her parents brought to him. Another girl was sick with a terrible disease: her whole body was covered with festering wounds with worms. The monk anointed her body with oil, over which he read a prayer to the Lord, and she became healthy.

One day they brought a young man possessed by a demon to Saint Macarius. The devil who possessed him demanded a huge amount of food, which immediately came out of the possessed man’s mouth in the form of steam. The mother begged Macarius to save her son from demonic possession. The monk fasted and prayed for seven days and cast out the devil.

Prayer 1, Saint Macarius the Great

Among all the prayers, it is the morning prayer to this saint that has the greatest power. The text of the prayer in Russian must be read immediately after waking up, along with other morning prayers.

God, cleanse me, a sinner, for I have never done good before You, but deliver me from evil, and may Your will be done in me, so that I may not open my unworthy lips to condemnation and praise Your holy name, the Father, and the Son, and The Holy Spirit now, and always, and unto ages of ages. Amen.

Death and canonization

Blessed Macarius spent 60 years in the desert in prayerful service, constantly repenting of his sins, and at work. The monk lived to be 97 years old. Macarius learned about his imminent death from a dream in which messengers from the Lord, Saints Anthony and Pachomius, appeared to him.

Macarius the Great, saying goodbye, blessed his followers and like-minded people. His last words were: “Into Your hands, O Lord, I commend my spirit.” The Orthodox protected the holy relics from desecration by Muslims. Since 1754, they have been buried in a Coptic monastery founded by Macarius the Great of Egypt.

During the period of the undivided Church, canonization took place without the adoption of acts. Canonization for special services to the Church applied to patriarchs, prophets, apostles, and ascetics.

Creative heritage

The constant spiritual work of Macarius the Great was reflected in theological works. For the Orthodox world, 50 conversations, 7 instructions and 2 messages have been preserved. In his revelations, the Monk Macarius reflects on how to achieve the union of the soul with God, analyzing his own life path and the experience of other Egyptian ascetics. In conversations, Macarius the Great gives an interpretation of the Bible in allegorical form.

Saint Macarius preaches bodily asceticism and constant observance of the commandments of God for the upliftment of spiritual life.

Explanations and excerpts from the theological works of St. Macarius:

- Why is the soul a container of darkness if God created it? Because Adam, having violated God’s Covenant, allowed sin into her, where the evil one now finds himself. Only a soul that has believed in God and accepted the Holy Spirit into itself is capable of defeating the dark passions that penetrated into it as a result of original sin.

In order for the soul to be eternally close to the Lord, it must become dead to earthly life, where the evil one reigns. She must reincarnate into another entity that can access divine truths.

To destroy the sinful spirit, one must pray until the soul can receive and be filled with the Holy Spirit. Because prayer is not just words, but work done by the soul. Without the spiritual benefits that prayer gives, a person is poor in soul, and he must be in constant sadness, sorrow, and crying. One must continually turn to the Lord and ask in faith in order to gain true life.

Like the physical essence, true life for the soul, which is a cast of the Divine image, can only continue with the perception of spiritual food, drink, and clothing.

- Only God can liberate from the unclean, who has acquired dominion over the soul and body of a person. The Lord gave the Messiah, who helped throw off the shackles of slavery to the devil.

By sinning, man was transformed from being perfect to being disobedient to God's law. He is hidden from God by the devil's clothing: slander, unbelief, fearlessness, arrogant arrogance, greed, debauchery. Jesus atoned for human sin, and people can again become perfect and live forever in the Kingdom of God.

- A Christian who wants to live with God in his soul, first of all, must acquire the gift of reliably distinguishing between good and evil. There are few people who were able to remain faithful to the indivisible love for the one God and gave up everything. Temptations encountered in worldly life turn us away from heavenly love due to weakness, timidity, and excessive love for something earthly.

What is dear to a person in the world comes first for him, weakening him in the fight against temptations. This is the vicious power of sin that tests every person’s loyalty to the Lord.

Only those Christians will be able to fully accomplish the feat of serving the Lord who, of their own free will, have renounced worldly love. To pass the test, you must constantly monitor your desires in order to immediately ask God to deliver you from the desire for pleasure and participation in worldly problems.

- The main thing in turning to the Lord in prayer is to do it in silence, peace of mind, without distractions or attracting other people’s attention. The soul, cleansed from passions, will unite with the Holy Spirit and be filled with joy, love, mercy, and kindness.

To fill the soul with the Holy Spirit, a Christian must observe the divine commandments, exclude worldly concerns from his consciousness, so that the mind does not react to earthly problems. Hourly prayer addressed to the Lord is what the believer’s mind should be full of.

You can defeat sin, which is present in every person, only by constantly forcing yourself to humility:

- considering himself unworthy before any of the people;

- avoid fame;

- approval.

Good deeds and exploits can be dedicated to God alone.

Efforts of will must be aimed at overcoming character flaws. A true Christian must be merciful, generous, patient, despite insults and humiliation. If he finds it difficult to force himself to pray, he should not give up. God will see how a person curbs himself through an effort of will, and will give spiritual fruit: prayer, through which the feeling of true love, meekness, and kindness will come.

If a Christian forces himself to pray, but does not fulfill the commandments of God, does not force himself to meekness, wise humility, love for his neighbor, then he is given the grace of prayer. He will receive peace and joy in his soul, but his moral essence will not change.

Every Christian must force himself, despite his heart, both to prayer and to wise humility, love, meekness, sincerity, simplicity of heart, and patience. He must fight his pride, considering himself a beggar and the worst of people, wean him from idle conversations and thoughts, not express his feelings by shouting, and not get irritated.

Anyone who wants to truly serve God will have to fight against worldly temptations, moving away from entertainment, sinful passions, and spirits of evil. The Holy Prophets, Apostles, and Martyrs remembered and kept in their hearts the commandments of the Holy Spirit, following them not only in words, but also in deeds: renouncing wealth, fame, and pleasures. As a result of this, there was no place for irritability in their souls, but love reigned. Those who participate in this grace love all people, including evil blasphemers and persecutors, forgiving offenses and praying to God for them.

- A virtuous lifestyle leads to spiritual joy, because virtues are links in one chain, dependent on each other. Prayer comes from the heart, from love. Love arises from joy. The source of joy is meekness, which is born from humility.

Humility is cultivated during service to the Lord; service comes from hope; the source of hope is faith. Faith is impossible without obedience, and obedience is impossible without simplicity of needs.

And bad deeds are the generation and continuation of each other:

- anger - from nervousness;

- nervousness - from pride;

- pride - from love of fame;

- love of fame comes from unbelief;

- lack of faith - from hardness of heart;

- hard-heartedness - from negligence;

- negligence - from laziness;

- laziness - from despondency;

- sadness - from impatience;

- impatience is from lust.

The earthly life of a true Christian, as Macarius the Great teaches, with all the struggle against worldly temptations and moral and spiritual labors, is the preparation of the soul for the acceptance of the Kingdom of Heaven.

The spiritual heritage of the saint remained with Christian believers forever. The Holy Church included the ascetic prayers of St. Macarius in morning and evening services (1st morning prayer, 1st and 4th evening prayers).

How does the icon of St. Macarius the Great help?

Through the icons of His saints, the Lord sends us what we ask for, useful for our souls. The saints, just like us, who have walked the earthly path, know our needs. They experienced the same experiences, overcame similar earthly difficulties. When we ask a saint for intercession, we ask that he convey our prayer to God and that the saint’s prayers will be heard faster than our sincere appeal to them. The icon of St. Macarius the Great helps to establish a prayer connection with the patron saint. Having in front of us the visual image of Saint Macarius, our prayer is not dissipated into empty ideas and dreams. And according to the faith of the one who asks, the Lord, through His saints, gives us what we ask.

They pray to St. Macarius the Great:

— About strengthening faith — About help in organizing earthly affairs — About healing of bodily and spiritual infirmities.

Truly wonderful is God in His saints! Dear believers, brothers and sisters! Do not doubt the help of St. Macarius! Open your heart to him in sincere prayer and he will hear us, heal spiritual and physical infirmities, and help in the successful arrangement of earthly affairs.

Do not forget that in order for a miracle to happen, we ourselves must take care: regularly, with attention, read the prayer, do deeds of faith and love. And don’t forget to give thanks: to thank all the people sent to us by the grace of God to solve our life’s troubles, who shared our joy and sorrow. To thank the Saint, whose prayerful support our heart yearned for, because how many people pray to him for help, but he heard and helped us too. And most importantly, thank the Lord for His boundless love for mankind. He gave the world His saints and every second helps us, people who hope for His great mercies.

Everything in the world happens according to the wise providence of God. Difficulties and sorrows, success and joys. Through earthly trials the Lord strengthens us. By helping each other, praying to the heavenly saints, we are more firmly united in the One Church of Christ. And we believe that Saint Macarius will hear all our prayers and show us the boundless mercy of our Lord Jesus Christ. Thank God for everything!

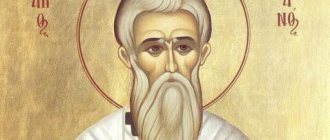

Iconography

On the icons the Monk Macarius of Egypt is depicted as an old man with a long gray beard to the waist or below, with gray hair. The gaze of large, stern eyes is fixed on those praying. The sacred halo shines above the head of the saint.

In images, a Christian hermit can be depicted naked, covered only by a beard, or in a tunic, waist-length or full-length. The image without clothes is a reminder of the ascetic lifestyle of the saint, who was so absorbed in spiritual improvement and communication with God that he forgot about the material side of earthly life.

Macarius's hands are either prayerfully folded on his chest, which means humility, or he makes a gesture with his palms turned towards the believers - as a warning against the temptations of the evil one. The images of the scroll in the hands are the spiritual instructions that the saint gave to his disciples. There are images where the Cherub stands next to Macarius, the Venerable Onuphrius, and Peter of Athos.

Creations

Published in Russian:

- Spiritual conversations. Per. priest Moses Gumilevsky. M., 1782. Ed. 2nd, M.. 1839. Ed. 3rd. M., 1851. The same (2nd lane). — “Christian reading.” 1821, 1825, 1827, 1829, 1834, 1837, 1846. The same (3rd trans.). Ed. 4th, Moscow. Theological Academy. Sergiev Posad. 1904.

- Ascetic messages. Per. and note. B. A. Turaeva. - “Christian East”, 1916, vol. IV, p. 141-154.

The teaching of St. Macarius is also stated: “Philokalia.” T. I. M., 1895, p. 155-276.

Lyrics

On the days of memory of Macarius the Great, an akathist, kontakion, and troparion are read in church. Orthodox believers turn to the icon of the saint with prayer requests.

Troparion

Desert dweller, and in the flesh an Angel, and a miracle worker appeared, Our God-bearing Father Macarius: by fasting, vigil, and prayer, we received Heavenly gifts, healing the sick and the souls of those who come to you by faith. Glory to Him who gave you strength, glory to Him who crowned you, glory to Him who heals you all.

Kontakion

Having passed away the blessed life of life with the faces of martyrdom, you worthily settled in the land of the meek, God-bearing Macarius, and having inhabited the desert like a city, you received grace from the God of miracles, with the same we honor you.

Prayer

Prayers are offered to Macarius of Egypt in the morning, during times of adversity and sadness.

First

To You, Lord Lover of Mankind, having risen from sleep, I hasten, and I take up deeds pleasing to You, according to Your mercy, and I pray to You: help me at all times, in every matter, and deliver me from all evil vicissitudes in this world and from the devil. help, and save me, and bring me into Your eternal Kingdom. For You are my Creator and Provider and Giver of all good. And in You is all my hope, and I send up glory to You, now, and always, and forever and ever. Amen.

Second

Oh, Rev. Father Macarius! We pray to you, unworthy ones, by your intercession, ask our All-Merciful God for mental and physical health, a quiet and pious life and a good answer at the Last Judgment of Christ. With your prayers, extinguish the arrows of the devil, so that sinful malice may not touch us, and having piously ended our temporary life, we may be worthy to inherit the Kingdom of Heaven and together with you glorify the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit forever and ever. Amen.

Third

Oh, sacred head, reverend father, most blessed Abvo Macarius, do not forget your poor to the end, but always remember us in your holy and auspicious prayers to God. Remember your flock, which you yourself shepherded, and do not forget to visit your children. Pray for us, holy father, for your spiritual children, as if you have boldness towards the Heavenly King, do not be silent for us to the Lord, and do not despise us, who honor you with faith and love. Remember us unworthy at the Throne of the Almighty, and do not stop praying for us to Christ God, for you have been given the grace to pray for us. We do not imagine that you are dead, even though you have passed away from us in body, but even after death you remain alive. Do not give up on us in spirit, keeping us from the arrows of the enemy and all the charms of the devil and the snares of the devil, our good shepherd. Even though your relics are always visible before our eyes, your holy soul with the angelic hosts, with the disembodied faces, with the heavenly powers, standing at the Almighty Throne, rejoices with dignity. Knowing that you are truly alive even after death, we bow down to you and pray to you: pray for us to Almighty God, for the benefit of our souls, and ask us time for repentance, so that we may pass from earth to heaven without restraint, from the bitter ordeals of the demons of the air princes and may we be delivered from eternal torment, and may we be heirs of the Heavenly Kingdom with all the righteous, who from all eternity have pleased our Lord Jesus Christ; to Him belongs all glory, honor and worship, with His Beginning Father and with His Most Holy and Good and Life-Giving Spirit, now and ever and ever. Amen.

Buy an icon of St. Macarius the Great

In the Radonezh icon painting workshop you can buy or order a handwritten icon of the Holy Venerable Macarius the Great. Call us and we will help you choose a plot, a compositional solution for the icon, its optimal size and design, or we will write an icon according to your sample.

Free delivery throughout Russia.

If desired, the icon can be consecrated in the Holy Trinity Sergius Lavra.

The image of St. Macarius the Great, made by the icon painters of the Radonezh workshop, like any handmade icon, carries within itself the living warmth of human hands and a loving heart. Each icon painted with love is unique and inimitable.

Peace and goodness to you Dear brothers and sisters, and may the holy saint of God, Macarius of Egypt, accompany you throughout your entire life’s journey.

Similar icons:

Vera Rimskaya 13000 ₽

Alexander Sevastiysky 13000 ₽

Wedding icons with engraving 46000 ₽

Icon of the Lord Pantocrator