Christians in the first centuries of ours most often ended their lives under torture or as a result of the death penalty - faith in Christ was dangerous. However, it is thanks to those sufferers that today each of us has the opportunity to attend church and grow in faith.

One of the famous martyrs of the 6th century AD. There was Maxim the Confessor, who was known not only for his theological works, but also for his active struggle against all heresy. He was one of the first to formulate and express the theory of diopheliteism - the idea of two natural wills in Jesus, and for this he accepted torture and was exiled to Colchis.

The works of this Christian theologian were subsequently used repeatedly to write the doctrines of the Orthodox faith, and his persistent faith and will inspire many Christians today.

early life

Little is known about the childhood of St. Maximus the Confessor. According to the Greek and Georgian Lives, he belonged to a noble, wealthy family. Maxim's small homeland was Constantinople. The probable time of his birth dates back to 580.

It is known that the future Confessor was baptized at an early age and, from childhood, was brought up in the spirit of strict compliance with God's law. Maxim's parents, the pious John and Anna, treated their son with love, but did not particularly spoil him (despite the wide material opportunities available for this), but kept him in pedagogical rigor, protecting him from stupidity and childish mischief.

While growing up, Maxim received a proper, comprehensive education. In the art of speech and rhetoric, he was in many ways superior to his peers, and in knowledge of philosophy it was difficult to find his equal. It is noteworthy that, as a literate Christian, Maxim accepted philosophy not blindly, but soberly, prudently, and critically.

Despite his noble origin and excellent education, Maxim was not only a very virtuous person, but also surprisingly modest. Possessing such traits of character and intelligence, it was difficult for him to remain unknown.

Emperor Heraclius, seeing in him a good potential assistant, called him to himself and appointed him to the post of first secretary in his office.

While working in this position, Maxim proved himself to be the best. He easily grasped the royal commands, knew how to quickly and balancedly summarize and write down important, meaningful information, and more than once himself gave appropriate and completely worthy advice to whomever he should. The emperor valued such employees, and Maxim soon achieved great influence at court.

Meanwhile, fame, court pomp, and honor did not captivate Maxim. More than all these excesses, he valued wisdom. By the time he had achieved a position of prominence that many of his compatriots could only dream of, a new heresy had become widespread: monothelitism. This heresy was all the more dangerous because it had external appeal and was supported by the highest church and state authorities (before the time of its condemnation at the VI Ecumenical Council, several Patriarchs, many bishops and priests joined it).

Youth and adolescence. Excellent abilities and brilliant education

History has not preserved the details of the childhood and youth of the Monk Maxim. It is known that he was born in 580 in Constantinople, into a noble family. Having an extraordinary mind and rare abilities for philosophy, he received an excellent education and chose a political career.

In 610, Emperor Heraclius appreciated Maximus's mental abilities and Christian virtues, and appointed him as his first secretary.

580

Maxim the Confessor was born this year

From his youth the monk had a great desire for monastic life. Fame, wealth and power could not deter him. After 3 years, he leaves his promising position for worldly life and becomes a monk.

Monastic life

Realizing the danger of the current situation and not wanting to participate in it due to his devotion to Orthodoxy, the Monk Maxim, unexpectedly for those around him, abandoned secular well-being and entered the Chrysopolis monastery.

In the monastery he devoted himself to prayers and deeds. Over time, the brethren began to treat him so trustingly that they decided to elect him as their abbot (this fact was repeatedly disputed by critics, due to the fact that Maxim did not have holy orders). He, who had never strived for glory and, out of humility, did not consider himself worthy of such a spiritual title, resisted, but due to tireless requests, he agreed.

Realizing that he must set an example for the brethren as an abbot, the Monk Maxim increased his exploits even more.

Notes[ | ]

- ↑ 1 2 Orlov I.A.

Works of St. Maximus the Confessor. Conclusion - John Meyendorff

. Introduction to Patristic Theology. Ch. 5. Continuation of Christological disputes. Venerable Maximus the Confessor

Sidorov A.I. Some aspects of the ecclesiology of St. Maximus the Confessor. C. 184- Catholic Doctors of the Church (unspecified)

(inaccessible link). Access date: April 16, 2022. Archived July 10, 2011. - The Sacred Congregation for the Causes of Saints ( Prot. Num. VAR.

7479/14) has not yet made changes to the list of Doctors of the Church. - ↑ 1 2 Berthold J.

Maximus the Confessor // Encyclopedia of Early Christianity / ed. E. Ferguson. - NY: Garland Publishing, 1997. - ISBN 0-8153-1663-1. - Maxim, St. Confessor // Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church / ed. F. L. Cross. - London: Oxford Press, 1958. - ISBN 0-19-211522-7.

- Catholic Encyclopedia January 12, 2007: “This great man came from a noble family of Constantinople.”

- prot.

G. Florovsky Byzantine Fathers of the V-VIII centuries. Venerable Maximus the Confessor. - Catholic Encyclopedia for March 7, 2007.

- Kartashev A.V.

Ecumenical Councils. Maxim the Confessor. - Kartashev A.V.

Ecumenical Councils. Justinian I the Great (527–565). Religious policy of Heraclius (so-called unions) - Pauline Allen, Bronwen Neil

. Maximus the Confessor and his Companions: Documents from Exile. OUP Oxford, 2003. - P.12 - Catholic Encyclopedia for January 15. 2007: “The first action of Maximus, known to us on this occasion, was a letter sent to Pyrrhus, later the abbot of Chrysopolis...”

- Kartashev A.V.

Ecumenical Councils. Rehabilitation of Rome. Pope John IV. - Philip Schaff.

History of the Christian Church, Vol.IV: Medieval Christianity. AD 590—1073 (online edition)§ 111, January 15, 2007. - "Maximus the Confessor" in The Westminster Dictionary of Church History

, ed. J. Brower (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1971) (ISBN 0-664-21285-9). This is commonly known as the First or Second Lateran Council - Eg: J. Berthold.

Maximus Confessor. // Encyclopedia of Early Christianity, (New York: Garland, 1997) (ISBN 0-8153-1663-1). - D. H. Farmer.

The Oxford Dictionary of the Saints (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987) (ISBN 0-19-869149-1) p.288. Martin is the last bishop of Rome to be celebrated as a martyr. - A.V. Kartashev notes that in the Russian Church the emperor was commemorated before the bishopric, so this argument would not have force, but on the contrary would confirm the position of the accusers

- Life of our venerable father Maximus the Confessor // Lives of the saints in Russian, set out according to the guidance of the Chetyih-Menya of St. Demetrius of Rostov: 12 books, 2 books. add. - M.: Moscow. Synod. typ., 1903-1916. — T. V: January, Day 21.

- A. V. Kartashev. Ecumenical councils. The trial of Maximus the Confessor

- The history of the discovery of the relics of St. Maximus the Confessor

- For example, from the life of St. Maxim Orthodox Church in America: “Three lights appear on Maximus’s memorial day on his grave, reminding us that he is still a lamp of Orthodoxy. Through his prayers many healings occurred.”

- Archbishop Stefan (Kalaijashvili).

The story of the discovery of the relics of St. Maximus the Confessor. //Orthodoxy.ru 02/28/2012 - Catholic Encyclopedia for March 7, 2007

- "Maximos, St., Confessor" in Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, ed. F. L. Cross (London: Oxford Press, 1958) (ISBN 0-19-211522-7). also see Maxim Mystagogy

and

Ambigva - "Maximus the Confessor" in M. O'Carroll, Trinitas: A Theological Encyclopedia of the Holy Trinity

(Delaware: Michael Glazier, Inc, 1987) (ISBN 0-8146-5595-5). - Michurina

Yu.F. Man in the philosophical and theological system of Maximus the Confessor - Lars Thunberg. Microcosm and Mediator: The Theological Anthropology of Maximus the Confessor 2nd Edition ISBN 978-0812692112 ISBN 081269211X

- Catholic Encyclopedia for March 7, 2007.

- "Maximos, St., Confessor" in Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, ed. F. L. Cross (London: Oxford Press, 1958) (ISBN 0-19-211522-7).

- Hieromonk Artemije Radosavljević, Τὸ Μυστήριον τῆς Σωτηρίας κατὰ τὸν Ἅγιον Μάξιμον Ὁμ ολογητήν. Αθήνα, 1975. English translation of part of the dissertation: Bishop Artemije Radosavljević Why Did God Become Man? The Unconditionality of the Divine Incarnation. Deification as the End and Fulfillment of Salvation According to St. Maximos the Confessor - Source: Τὸ Μυστήριον… (Athens: 1975), pp. 180-196 (The mystery of salvation according to Saint Maximus the Confessor)

- The Oxford Dictionary of the Saints

(D. H. Farmer) does not feature Maximus at all, which is an excellent example of how the West has missed Maximus for many years.

Systematic Theology

, written in the late 1990s, is an example of how Western theologians discovered Maximus.

See also Maximus the Confessor

by M. O'Carroll,

Trinitas: A Theological Encyclopedia of the Holy Trinity

(Delaware: Michael Glazier, 1987 - ISBN 0-8146-5595-5); O'Carroll called Hans Urs von Balthasar a "pioneer" in the discovery of Maxim by the West. - V. Tsypin. The confessional feat of St. Maxim and his theology. //Orthodoxy.ru, 02.16.2017

- Khosrovik Targmanich.

Dogmatic works / trans. from ancient Armenian and preface by Khachik Grigoryan. - Yerevan: Ankyunakar, 2016. - P. 53. - 144 p. — ISBN 9789939850207.

Maxim's life in the West

After some time, the Monk Maxim left the monastery, left his homeland. What exactly prompted him to take this step is difficult to say. According to some sources, one of the central motives was the growing influence of heretics (the same Monothelites). According to other sources, from the Chrysopolis monastery (from which he retired in 624 or 625, having stayed there for more than 10 years), the monk moved to the monastery of St. George (located in Cyzicus), and only then, in 626, due to the onslaught Persians and Avars, leaving this monastery, moved to the West.

It is believed that at first Maximus the Confessor stayed on the island of Crete. Here he held several debates with the Monothelite bishops. After Crete he ended up in Cyprus.

There is reason to assert that around 630 the Monk Maximus visited North Africa. Around the same period, Sophronius, the future Patriarch of Jerusalem, an outstanding fighter against the Monothelites, found himself in Africa. A warm relationship began between Sophrony and Maxim. Maxim willingly listened to the instructions and advice of the blessed elder.

Information about the detailed circumstances of his life during this period is extremely scarce. We don't even know its duration. Obviously, this stage was rich in the fruits of Maxim’s writing.

Once in Rome, he intensified his forces in the fight against monothelitism. In this regard, the monk corresponded with various persons, instructed people by spoken word, supported the activities of Pope John IV directed against heretics, and was among the main initiators of the convening of the Local Council.

After 642, Maximus the Confessor went to Africa. Here he showed himself to be a zealous, passionate, but at the same time sober and wise fighter. During his stay in Africa, he completed the formation of his doctrine of the presence in Christ, one in Hypostasis, of two natural (essential) wills: Divine and human.

Despite the fact that Maxim did not have holy orders, being a simple monk, he had extremely enormous authority in countering heretics. The laity, priests, and bishops listened to his admonitions. The Exarch of North Africa often consulted with him on various religious issues.

In 645, the famous dispute between Saint Maximus and Pir took place. Pir was publicly exposed and defeated, after which he realized and admitted that he was wrong and entered into communion with the Orthodox Church.

In 646, Maximus the Confessor again found himself in Rome, and again at the forefront of the fight against heresy.

Pope Theodore was in a trusting relationship with Maxim. Once Maximus had to intercede for the head of the Roman Church, smoothing over his careless statement regarding the procession of the Holy Spirit and from the Son. Then Maxim was able to say that since Pope Theodore recognizes the One Principle in the Most Holy Trinity exclusively with the Father, his expression should not be perceived as malicious. This intercession caused many critical exclamations against Maximus from Greek theologians.

The relationship between the Monk Maxim and Theodore’s successor, Pope Martin, also developed well. Pope Martin, like Maximus the Confessor, tried to use every opportunity and all his influence to counter the spread of monothelitism. In order to refute the heresy, he convened the Lateran Council. There is a legend that one of the initiators of the Lateran Council was St. Maximus (among the signatures on the monks’ petition to the Council, his signature appears in one of the last places).

Prologue to Elpidius

In addition to the “Sermon on the Ascetic Life,” I am sending you, honorable Father Elpidius, also the essay “On Love” in hundreds of chapters equal to the four Gospels. It may not meet your expectations, but we did our best. However, let it be known to your holiness that this work is not the fruit of my thought: I read the works of the holy fathers and collected from them what directs the mind to my subject. And I have condensed the lengthy discussions into a few short chapters, so that they are easy to understand and better remembered. Sending them to Your Reverence, I ask you to read favorably, looking for one benefit, not to pay attention to the unsophistication of the style and to pray for me, unworthy and devoid of any spiritual fruit. I also ask you not to think that [this essay] was written to bother [you]: I was only carrying out what was assigned to me. I say this because today there are many of us who bother us with speeches, but there are few of those who educate and are themselves educated by deeds. [I also ask] to delve into the [meaning] of each chapter with all diligence. For I think that not everything is understandable for everyone, but many things will require additional research from many, although it seems to be said very simply. Perhaps in these chapters you will find something useful for the soul. But, of course, this will be revealed by the grace of God to those who read them with thoughts far from excessive inquisitiveness, with the fear of God and love. And whoever turns to this or any other work not for the sake of spiritual benefit, but strives to find an [unsuccessful] expression to reproach the writer and vainly show himself wiser than him, nothing useful will ever be revealed to him anywhere.

Confessional crown

Emperor Constant, having learned about the work and definitions of the Lateran Council, was inflamed with anger and ordered Pope Martin and the monk Maximus to be brought to Constantinople.

The Monk Maximus was arrested and escorted to the capital of Byzantium around 653, at approximately the same time as St. Martin. The latter was convicted and sentenced to exile in Crimea, where he died under the weight of punishment. The trial of Maximus took place in 655. His devoted student, Anastasia, was also tried along with him.

Maxim was accused of quite high-profile, but mostly absurd crimes. In addition to inciting hatred towards the sovereign, the list of accusations included, for example, that he almost single-handedly surrendered Egypt and Africa to the Saracens, and participated in a rebellion together with the exarch of North Africa. But Maxim denied the slander.

We also touched on theological topics. The monk gave a detailed, well-reasoned answer to accusations of spreading forbidden teachings. But, alas, human truth does not always agree with God’s Truth. After the trial, Maximus was sent into exile in Visia (the territory of Thrace). Here he was left without a livelihood, suffered humiliation and deprivation.

Meanwhile, the imperial court soon made an attempt to restore relations with Maxim: they were looking for an opportunity to give the emperor and heretical bishops a chance to “prove” that they were right.

For this purpose, an embassy headed by Bishop Theodosius came to the holy sufferer. During the conversation that took place on this occasion, the monk not only did not change his convictions, but also assured those who arrived of the need to anathematize the heresy leaders. Struck by Maxim’s firmness, the ambassadors hesitated, and then, under the pressure of indisputable evidence, were forced to admit that he was right. Leaving Maxim, they no longer harbored feelings of enmity towards him.

Eight days later, one of the ambassadors, consul Paul, returned to Maxim. According to the order of the emperor, Maxim was to be escorted with great honor to the monastery of St. Theodore (according to various sources, this monastery was located either in Regia or in Constantinople), which was done.

Here the monk was visited by two imperial envoys, patricians Epiphanius and Troilus, and explained to Maxim that because of his stubbornness, many believers did not want to enter into unity with them (the Monothelites). Having expressed the demand to recognize the doctrine of one will in Christ, which he rejected, they promised that if he agreed, great honors awaited him.

Despite the obvious threat, even if slightly retouched, Maxim reaffirmed his determination to fight to the end. Then, overwhelmed by a flash of animal rage, the patricians rushed at the saint and began to beat him. Only the intervention of Bishop Theodosius, who was present at this massacre, moderated their ardor.

After yet another unsuccessful attempt to bring Maxim to a compromise convenient for the authorities, he was again sent into exile: again to Thrace, but this time to Perveris.

In 658, the last attempt to call Maxim to “humility” was made by Patriarch Peter. To do this, he sent his representatives to him. In the format of the conversation, Maxim was told that if he refused, he would face anathematization and the death penalty, but he was adamant.

In 662, another trial took place. Maximus the Confessor was subjected to severe scourging, his tongue was cut out, his right hand was cut off, he was taken out to the square and began to be led around it like a villain, shouting and mocking.

After this outrage, Maxim was sent into exile. When they reached the territory of Georgia, they stripped the sufferer and took away his last property. Then he was imprisoned in the Schimari fortress.

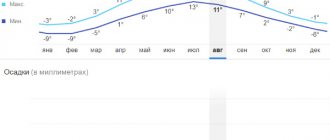

Shortly before his death, Maxim the Confessor received a vision in which it was revealed to him that he would appear before God on August 13. And so it happened: on August 13, the true warrior of Christ reposed and departed to the Kingdom of Heaven.

Further events[ | ]

Despite the Council's approval of Maximus' theological position at the Sixth Ecumenical Council, neither he nor Pope Martin were not only glorified, but also not rehabilitated. The attitude of many bishops towards them was still ambiguous, and they still remained state criminals. Maxim gained fame after his death, which was facilitated by numerous miracles at his grave[24].

Only at the VII Ecumenical Council, due to the fact that the works of the Reverend contained the most important arguments in defense of icon veneration, he was rehabilitated. Then there was a second period of iconoclasm, which lasted until the Council of Constantinople in 843, during which recognition of the holiness of Maximus the Confessor was impossible[25].

In the Roman Catholic Church, the veneration of Maximus began even before the creation of the Congregation for the Causes of Saints.

The memory of St. Maxim is celebrated on February 3 (January 21, old style) and August 26 (August 13, old style) (transfer of relics).

Creative heritage

As a church writer, St. Maximus the Confessor is known to the general reader primarily for his Christological writings. Meanwhile, the range of theological issues revealed by his work is much more extensive.

The most popular works include: Ambigvas to John (about difficulties) 1-30, On various difficult passages (aporia), Ambigvas to Thomas (about various perplexities of Saints Dionysius and Gregory), Questions and perplexities, Questions and answers to Thalassia, Chapters on theology and economy of the incarnation of the Son of God, Mystagogy, To Theopemptus the scholastic, Epistle on the being and hypostasis, Interpretation of the Lord's Prayer, Interpretation of the 59th Psalm, Four hundred chapters on love, A Word on the Soul, Letters, etc.

Reception[ | ]

The Western Church made extensive use of quotations from the works of Maximus the Confessor in John of Damascus's Accurate Exposition of the Orthodox Faith, but Maximus's works generally did not attract the attention of Western theologians (except John Scotus Eriugena) until recently[34].

In the Orthodox Eastern Church of the Byzantine tradition, on the contrary, Maximus's own works, although not all (since many were forgotten or lost during the anathematization of St. Maximus), had a strong influence throughout its history. Already John of Damascus included in his works actually quotations from the texts of Maximus the Confessor, without mentioning only his name, as at that time he had not yet been rehabilitated. Archpriest John Meyendorff called Maxim "the true father of Byzantine theology." According to the testimony of Princess Anna Comnena, her mother read Maxim’s works with enthusiasm[35].

Subsequently, late Byzantine theologians, such as Simeon the New Theologian and Gregory Palamas, became the intellectual heirs of Maximus. Moreover, many of Maximus's works are included in the Greek Philokalia, a collection of some of the most famous Greek Christian writers.

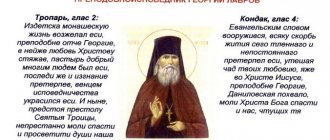

Kontakion to St. Maximus the Confessor, tone 6

The Tri-radiant Light, which has entered into your soul, / is a chosen vessel to show you, O all-blessed One, / who is the Divine end, / You speak of inconvenient understandings, O Blessed One, / and preach the Trinity to all, Maxima, clearly, // The Pre-Essential, the Beginningless.

Kontakion to St. Maximus the Confessor, tone 8

The Trinity of the zealot and the great Maxim, / teaching clearly the Divine faith, / to glorify Christ in two natures, the wills and actions of being, / in songs worthy of faith, we honor, crying out: Rejoice, preacher of the faith.

Literature[ | ]

- Benevich G.I., A Brief History of “Fire” from Plato to Maximus the Confessor

, St. Petersburg: Publishing House of the Russian Chemical Academy, 2013, 315 pp. (Byzantine Philosophy, vol. 11; Smaragdos Philocalias). - Epifanovich S. L.

St. Maximus the Confessor and Byzantine theology - Kiev, 1915. Republished: M.: Martis, 1996; Supplement to the series “Patristic Heritage”. 220 pp. - Epifanovich, S. L.

Materials for the study of the life and works of the teacher. Maximus the Confessor. - Kyiv, 1917. - Kuzenkov P.V.

Logos. World. Man: the cosmology of Saint Maximus the Confessor. - Moscow: Sretensky Monastery Publishing House, 2022. - 150 p. — 2000 copies. — ISBN 978-5-7533-1586-1. - Life of our venerable father Maximus the Confessor // Lives of the saints in Russian, set out according to the guidance of the Chetyih-Menya of St. Demetrius of Rostov: 12 books, 2 books. add. - M.: Moscow. Synod. typ., 1903-1916. — T. V: January, Day 21.

- Kuzenkov P.V.

The providence of God and the freedom of man according to the works of St. Maximus the Confessor. - Moscow: Sretensky Monastery Publishing House, 2022. - 184 p. — 2000 copies. — ISBN 978-5-7533-1673-8. - Petrov V.V.

Maxim the Confessor: ontology and method in Byzantine philosophy of the 7th century. - M.: IFRAN, 2007. - 200 p. - Sec. 4, Ch. 2. Theological synthesis of the 7th century: St. Maxim the Confessor and his era // Lurie V.

M. History of Byzantine philosophy. Formative period. - St. Petersburg, Axioma, 2006. XX + 553 p. ISBN 5-901410-13-0

foreign language

- von Balthasar, Hans Urs. Cosmic Liturgy: The Universe According to Maximus the Confessor

. — Ignatius Press, 2003. ISBN 0-89870-758-7. - Bathrellos, Demetrios. The Byzantine Christ: Person, Nature, and Will in the Christology of Saint Maximus the Confessor

. - Oxford University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-19-925864-3. - Louth, Andrew. Maximus the Confessor

. — Routledge, 1996. ISBN 0-203-99127-3 - Nichols, Aiden. Byzantine Gospel: Maximus the Confessor in Modern Scholarship

. - T. & T. Clark Publishers, 1994. ISBN 0-567-09651-3. - Hieromonk Artemije Radosavljević

ολογητήν. — Αθήνα, 1975. English translation of part of the dissertation: Bishop Artemije Radosavljević Why Did God Become Man? The Unconditionality of the Divine Incarnation. Deification as the End and Fulfillment of Salvation According to St. Maximos the Confessor - Source: Τὸ Μυστήριον… (Athens: 1975), pp. 180-196 (The mystery of salvation according to Saint Maximus the Confessor) - Toronen, Melchisdec

.

Union and Distinction in the Thought of St Maximus the Confessor.

- Oxford University Press, 2007. ISBN 0-19-929611-1.