Church Slavonic language

Under the name of the Church Slavonic language

or the Old Church Slavonic language is usually understood as the language in which in the century. a translation of the Holy Scriptures and liturgical books was made by the first teachers of the Slavs, St. Cyril and Methodius. The term Church Slavonic language itself is inaccurate, because it can equally refer to both the later types of this language used in Orthodox worship among various Slavs and Romanians, and to the language of such ancient monuments as the Zograf Gospel, etc. The definition of “ancient” -Church Slavonic language” the language also adds little accuracy, for it can refer either to the language of the Ostromir Gospel, or to the language of the Zograf Gospel or Savina’s Book. The term "Old Church Slavonic" is even less precise and can mean any old Slavic language: Russian, Polish, Czech, etc. Therefore, many scholars prefer the term "Old Bulgarian" language.

The Church Slavonic language, as a literary and liturgical language, received in the century. widespread use among all Slavic peoples baptized by their first teachers or their disciples: Bulgarians, Serbs, Croats, Czechs, Moravans, Russians, perhaps even Poles and Slovinians. It has been preserved in a number of monuments of Church Slavonic writing, which hardly go back further than the century. and in most cases being in more or less close connection with the above-mentioned translation, which has not reached us.

Church Slavonic has never been a spoken language. As a book language, it was opposed to living national languages. As a literary language, it was a standardized language, and the norm was determined not only by the place where the text was rewritten, but also by the nature and purpose of the text itself. Elements of living spoken language (Russian, Serbian, Bulgarian) could penetrate Church Slavonic texts in varying quantities. The norm of each specific text was determined by the relationship between the elements of book and living spoken language. The more important the text was in the eyes of the medieval Christian scribe, the more archaic and strict the language norm. Elements of spoken language almost did not penetrate into liturgical texts. The scribes followed tradition and were guided by the most ancient texts. In parallel with the texts, there was also business writing and private correspondence. The language of business and private documents combines elements of a living national language (Russian, Serbian, Bulgarian, etc.) and individual Church Slavonic forms.

The active interaction of book cultures and the migration of manuscripts led to the fact that the same text was rewritten and read in different editions. By the 14th century I realized that the texts contain errors. The existence of different editions did not make it possible to resolve the question of which text is older, and therefore better. At the same time, the traditions of other peoples seemed more perfect. If the South Slavic scribes were guided by Russian manuscripts, then the Russian scribes, on the contrary, believed that the South Slavic tradition was more authoritative, since it was the South Slavs who preserved the features of the ancient language. They valued Bulgarian and Serbian manuscripts and imitated their spelling.

Along with spelling norms, the first grammars also came from the southern Slavs. The first grammar of the Church Slavonic language, in the modern sense of the word, is the grammar of Laurentius Zizanius (1596). In 1619, the Church Slavonic grammar of Meletius Smotritsky appeared, which determined the later language norm. In their work, scribes sought to correct the language and text of the books they copied. At the same time, the idea of what correct text is has changed over time. Therefore, in different eras, books were corrected either from manuscripts that the editors considered ancient, or from books brought from other Slavic regions, or from Greek originals. As a result of the constant correction of liturgical books, the Church Slavonic language acquired its modern appearance. Basically, this process ended at the end of the 17th century, when, on the initiative of Patriarch Nikon, the liturgical books were corrected. Since Russia supplied other Slavic countries with liturgical books, the post-Nikon form of the Church Slavonic language became the common norm for all Orthodox Slavs.

In Russia, Church Slavonic was the language of the church and culture until the 18th century. After the emergence of a new type of Russian literary language, Church Slavonic remains only the language of Orthodox worship. The corpus of Church Slavonic texts is constantly being updated: new church services, akathists and prayers are being compiled.

The vernacular basis of the Church Slavonic language

Carrying out his first translations, which served as a model for subsequent Slavic translations and original works, Kirill undoubtedly focused on some living Slavic dialect. If Cyril began translating Greek texts even before his trip to Moravia, then, obviously, he should have been guided by the Slavic dialect known to him. And this was the dialect of the Solunsky Slavs, which, one might think, is the basis of the first translations. Slavic languages in the middle century. were very close to each other and differed in very few features. And these few features indicate the Bulgarian-Macedonian basis of the Church Slavonic language [1]. The belonging of the Church Slavonic language to the Bulgarian-Macedonian group is also indicated by the composition of folk (not bookish) Greek borrowings, which could only characterize the language of the Slavs, who constantly communicated with the Greeks.

What unexpected meaning did the word “indifferent” once have?

Two people meet. One says to the other:

- How indifferent you are!

And he answers him:

- Thanks for the compliment!

Such a conversation may seem strange, or you may think that the other interlocutor is boasting about negative qualities. But everything could be simpler: both interlocutors used the word in a meaning that is unusual for us. Read more

Church Slavonic language and Russian language

The Church Slavonic language played a big role in the development of the Russian literary language [2].

The official adoption of Christianity by Kievan Rus (988) entailed the recognition of the Cyrillic alphabet as the only alphabet approved by secular and ecclesiastical authorities. Therefore, Russian people learned to read and write from books written in Church Slavonic. In the same language, with the addition of some ancient Russian elements, they began to write church-literary works. Subsequently, Church Slavonic elements penetrated into fiction, journalism, and even government acts. Church Slavonic language until the 17th century. used by Russians as one of the varieties of the Russian literary language. Since the 18th century, when the Russian literary language mainly began to be built on the basis of living speech, Old Slavonic elements began to be used as a stylistic means in poetry and journalism.

The modern Russian literary language contains a significant number of different elements of the Church Slavonic language, which have undergone to one degree or another certain changes in the history of the development of the Russian language. So many words from the Church Slavonic language have entered the Russian language and they are used so often that some of them, having lost their bookish connotation, penetrated into the spoken language, and words parallel to them of original Russian origin fell out of use.

All this shows how organically Church Slavonic elements have grown into the Russian language. This is why it is impossible to thoroughly study the modern Russian language without knowing the Church Slavonic language, and this is why many phenomena of modern grammar become understandable only in the light of studying the history of the language. Getting to know the Church Slavonic language makes it possible to see how linguistic facts reflect the development of thinking, the movement from the concrete to the abstract, i.e. to reflect the connections and patterns of the surrounding world. The Church Slavonic language helps to better and more fully understand the modern Russian language. (see article Russian language)

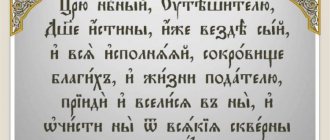

How to learn to read Church Slavonic

Despite its apparent complexity, Church Slavonic is our native language. Many words have not changed their meaning and are perceived intuitively. But if you want to learn to read correctly, then you need to remember the following:

- As it is written, so it is read. Words are not shortened, they do not “eat up” endings.

- Some words are written in abbreviation. A special sign (title) is placed above such words. You need to remember these words.

- the accents often do not coincide with modern ones.

- Some letters are read differently depending on their position in the word.

ABC of the Church Slavonic language

The alphabet used in modern Church Slavonic is called Cyrillic after its author, Kirill. But at the beginning of Slavic writing, another alphabet was also used - Glagolitic. The phonetic system of both alphabets is equally well developed and almost coincides. The Cyrillic alphabet later formed the basis of the Russian, Ukrainian, Belarusian, Macedonian, Bulgarian and Serbian alphabet, the alphabet of the peoples of the former USSR and Mongolia. The Glagolitic alphabet fell out of use and was preserved only in Croatia in church use.

Excerpts from the Church Slavonic language

Church Slavonic was the literary (book) language of the peoples inhabiting a vast territory.

Since it was, first of all, the language of church culture, the same texts were read and copied throughout this territory. Monuments of the Church Slavonic language were influenced by local dialects (this was most strongly reflected in spelling), but the structure of the language did not change. It is customary to talk about adaptations of the Church Slavonic language. Due to the diversity of monuments of the Church Slavonic language, it is difficult and even impossible to restore it in all its original purity. No review can be given unconditional preference over a wider range of phenomena. Relative preference should be given to Pannonian monuments, as they are more ancient and least influenced by living languages. But they are not free from this influence, and some features of the church language appear in a purer form in Russian monuments, the oldest of which should be placed after the Pannonian ones. Thus, we do not have one Church Slavonic language, but only its various, as it were, dialectical modifications, more or less removed from the primary type. This primary, normal type of Church Slavonic language can only be restored in a purely eclectic way, which, however, presents great difficulties and a high probability of error. The difficulty of restoration is further increased by the significant chronological distance separating the oldest Church Slavonic monuments from the translation of the first-teacher brothers.

- Pannonian translation (from the supposed “Pannonian” Slavs, into whose language the Holy Scripture was translated: a name created by the “Pannonists-Slovinists” and for “Bulgarians” having only a conditional meaning), representing the Church Slavonic language as the purest and freest from the influence of any there were no living Slavic languages. The oldest monuments of the Church Slavonic language, written in Glagolitic and Cyrillic alphabet, belong here.

- The Bulgarian version was especially widely used in the century, under Tsar Simeon, in the so-called golden age of Bulgarian literature. Around the half of the 12th century, a stronger influence of the well-known group of folk Bulgarian dialects is noticeable, giving the language of this era the name “Middle Bulgarian”. In this modified form, it continues to serve as the language of Bulgarian spiritual and secular literature until the 17th century, when it is replaced by the Central Symbolism of Russian liturgical books printed in Russia, and the living folk language (for example, in the so-called Ljubljana collection).

- The Serbian edition is colored by the influence of the living Serbian language; it served as a literary language both in the golden age of Serbian writing (XIV century) and after. Even at the beginning of the 19th century. (even before the reform of Vuk Karadzic, who created the literary Serbian language), TsSL (with an admixture of Russian coloring) served as the basis of the Serbian book language, the so-called “Slavic-Serbian”.

- The Old Russian version also appeared very early. The papal bull of 967 already mentions Slavic worship in Rus', which, of course, was performed in Church Slavonic. After Russia adopted Christianity, it acquired the meaning of a literary and church language and, colored by the increasingly strong influence of the living Russian language, continued to remain in the first of the above-mentioned uses until the half of the 18th century, and in exceptional cases - longer, having, in turn, proved , a strong influence on the book and literary Russian language.

Among other Slavs, the matter did not go beyond a few isolated cases of use.

Theology as a church science reveals to the modern secularized world the intellectual treasures accumulated over centuries of Christian spiritual culture. Moreover, in the consciousness that cognizes Christian theology, the experience of human intellectual efforts and Divine Revelation are firmly united in the intelligible world of the tradition of Orthodox speculation.

Patristic theology and Orthodox dogmatics were formed by the ascetic feat of intelligent work of holy Christian ascetics, who were representatives of a variety of countries and peoples. In Christianity, as is known, “there is neither Jew nor Greek... for you are all one in Christ Jesus” (Gal. 3:28), and this supra-ethnic, non-national vector of the Christian attitude to the world of national cultures indicates the direction of the conciliar unity of believers of different nationalities, speaking and praying in different languages. But so that believers can avoid the temptation of the “Babylonian pandemonium,” God has given people the language of worship - the sacred language of the Divine Liturgy, which embodies the speculative theology of the Church.

It is clear that in the historical path of Orthodox Christianity, the ancient classical languages had exceptional significance not only as the sacred languages of Christian worship, but also much more broadly - as forms of actual expression of Christian meanings and ideas, and therefore as a means of thought and theology.

This work makes an attempt to understand the linguistics of ancient classical languages as the basis of Orthodox Christian theology.

Unfortunately, the processes of secularization mentioned above have now embraced not only social and cultural life, but also had a powerful influence on church science and theology, which are perceived by the modern man in the street as unnecessary and fruitless intellectual entertainment. Protopresbyter Alexander Schmemann noted that the times are long gone when Gregory the Theologian “could not enter a bathhouse or a shop to buy bread without being grabbed by someone by the sleeve and asked: “Tell me, which is more correct - homoousios or omiousios?” 1]. In the famous course of lectures on dogmatic theology, Fr. Alexander o[2]. Therefore, for modern church life, an urgent need is the restoration and revival of the educational mission in the field of Orthodox theology - based on the intellectual heritage of Russian Theological schools.

It is important to restore and actualize in the minds of Orthodox believers the living connection between theology and the life of the Christian soul, the Logos-Word-Christ and the believing heart. The sacred language should not be dead in our minds, but the living language of church prayer, become a true kirigma - the language of preaching about Christ and the language of theology. At the same time, we must remember that “before we begin to engage in theology, we need to take a vow not to utter words outside of their exact meaning, for with what blood did the Church pay for finding words expressing the mysterious things contained in it, and how “divinely appropriate” they were? “(Basily the Great) words!”[3].

Indeed, in the history of Christianity, theology was formed essentially as an experimental science: in the fight against pagan cults, heresies and schisms, Orthodox dogma was established, expressed in the plastically strict and clear forms of the Greek language - in the Creed, in the oros of the Seven Ecumenical Councils, in the works of St. Fathers of the Church.

The very word “theology” in the first centuries of Christianity had a negative meaning for Christians. Thus, the ancient Greek poets who described pagan cosmogony and mythology in their writings were called theologians, and in Ancient Rome theology affirmed the cult of the emperor and imperial power. However, from the 4th century A.D., this term entered the Christian lexicon as a designation of a special teaching about Christ as God incarnate.

The era of early Christianity began to theology, of course, in Greek: “Christianity was expounded in the language of Greek philosophy. The whole miracle of the ancient Church was that Hellenism was churched. Paradoxically, the entire Jewish Old Testament heritage - with stories about the tribes of Israel, about the battles, victories and defeats of the Israeli people, with stories about how God acted in them - found expression in the language of Hellenic culture. The combination of these two reasons of different nature created early Christian theology”[4]. The Greek linguocultural basis made it possible to connect the highest potential of ancient Greek philosophical thought and dialectics as a resource of Eastern Christian theology. Although, of course, the process of Christianization of ancient Greek philosophy was long, controversial and very complex.

A specific understanding of theology also developed among Western Christians: the form of thinking about God was clothed here in the linguistic veil of the Latin language, which initially gave Western Christian theology a rationalized character and structurally formed analyticism inherent in its linguistic source. Several centuries after the adoption of Orthodox Christianity in Rus', Latin influence in the spiritual, educational and theological sphere will also be experienced by Russian Orthodoxy (both in a negative and, of course, in a constructive-positive sense). However, before we focus on the cultural and historical specifics of the theological language of Russian Orthodoxy, it is necessary to give a more detailed description of the historical stages of the formation of Christian theology in general and the language of theological science - in the sequence of their development.

Christian theology was originally a fundamentally scriptural and exegetical theology, i.e. it had its basis in Holy Scripture. And the Holy Tradition, dogmatically no less important in Orthodoxy, is sanctified and imbued with the biblical spirit of inspired writings.

The books of the Old and New Testaments, as the canonical text of the Bible, were formed gradually. As you know, the Old Testament books were originally written in Hebrew and Aramaic - from the 13th century. to the 1st century BC

An interesting fact (which philologists are well aware of) is that the Old Testament is the first book in world history to be translated into a foreign language (and into a language of a fundamentally different language family). Translation into ancient Greek was carried out in Alexandria in the 3rd – 2nd centuries. BC ("Septuagint" - "translation of the seventy", LXX), was adopted by the first Christians, played an important role in the formation of the Christian canon of the Old Testament, became the canonical text of Byzantine Christianity and the basis of the ancient Slavic and modern liturgical Bible of the Russian Orthodox Church. (From the ancient Greek text of the Septuagint, a translation of the text of the Old Testament into the Slavic language was made, which has both theological and liturgical significance). It is to the Septuagint that St. will appeal. fathers and teachers of the Church in their theological writings.

The Septuagint has a whole complex of fragments in which there are discrepancies with the so-called Masoretic text, one of the variants of the Hebrew text of the Tanakh (Old Testament). These discrepancies have become the subject of heated theological discussions in the history of Christianity. For example, in the history of Russian biblical studies of the 19th century, active polemics between Hebraic scholars on the topic of biblical translations are known. Some scholars clearly overestimated the meaning of the original Hebrew text (the Masoretic text) and interpreted discrepancies with it in the Septuagint as misunderstandings and distortions of the Greek translators. This point of view was shared by the professor of the Moscow Theological Academy P. I. Gorsky-Platonov[5]. Others defended the exclusivity of the Greek text, pointing to the facts of tendentious distortions of the original source made by the Masoretes. This position was held by Saint Theophan the Recluse[6]. A balanced line in this debate was represented by Saint Philaret (Drozdov), who proposed turning to the Masoretic text as one of the main sources, checking it with the text of the Septuagint, and giving preference to the Greek text in case of those discrepancies that are reliably attested in the Tradition of the Christian Church[7 ].

The outstanding Russian biblical scholar N. N. Glubokovsky already in the twentieth century argued that the Septuagint clearly expressed the idea of universal messianism as opposed to the nationalistic-messianic idea of the Masoretic text. The meaning of the Septuagint, in his opinion, consisted “in the personalistic-messianic character of the prophecies, which then quite logically and normally received Christian application in relation to the person of the Lord the Redeemer”[8]. N. N. Glubokovsky, characterizing the specific time of this translation - “in Alexandria during the time from Ptolemy Philadelphus to Ptolemy III Euergetes between 285 and 221 BC.” – notes that during this period “of course, there was no Christianity even in more or less clear foresight and there were no special messianic tensions in the supposed producing circles”[9]. And then the scientist makes a conceptually important conclusion: “a comparison of the Hebrew Masoretic Bible and the Greek translation of the LXX in objective historical coverage and impartial interpretation scientifically forces me to formulate in the end that the Greek interpretation reproduces a Jewish textual type independent of the Masoretic”[10].

In the mid-twentieth century, after the discovery of paleographically more ancient original Jewish texts (“Dead Sea Scrolls” / “Qumran Scrolls”), many problems of biblical textual criticism were resolved[11], and the theoretical arguments of N. N. Glubokovsky received additional confirmation[12]. It became obvious that the ancient Greek language of translation of the Old Testament texts updated the philosophical aspects and theological meaning of the Holy Scriptures.

So, for example, if the Hebrew meaning of the Old Testament Name of God Yahweh, revealed to Moses in Revelation at the burning bush (Ex. 3:14-15), is “Helper and Patron,” that is, the One who is actively present in the life of a believer and helps him in an unpredictable, miraculous way; then the Greek translation in the Septuagint, without canceling the original meaning of the Name, translates It sublimely and philosophically (in accordance with the spirit of the ancient Greek language) as “Existence,” that is, the One who exists initially and supports the existence of the created Universe[13].

The Greek translation of the fragment of Exodus 3:14 is: “Ego eyimi ho on” (subject - copula - nominal part of the predicate in the participle form of the verb to be). In the Slavic and Russian Bibles, this fragment is translated quite accurately: “I am the One” and “I am the One.”

Thus, in the Greek (and Slavic) translation, in comparison with the Hebrew text, a completely new meaning is born. If in the Hebrew text the Name of God has an extremely specific and vital promise of Presence here and now, then in the Septuagint translation the Name of God is introduced to the world of Greek wisdom through the philosophically based combination “ho he” (the Being), meaning the eternal and absolute existence of God.

The ancient Hebrew language was not characterized by the abstract categories inherent in the ancient Greek language and culture. Thanks to the Greek translation, it became possible to unite two fundamentally different types of cultures: the Middle Eastern (Jewish), with its characteristic existential experience of the relationship to the One God, and the ancient Greek, with its characteristic experience of abstract philosophical thinking. The combination of these two semantic plans, of course, reflects a single truth and foreshadows the Good News of Christ.

The main antinomy of the future Christian theology is born: the transcendence of the Absolute and His Presence, i.e. apophatics and cataphatics of the Incarnation. God is a transcendent Being. However, remaining an eternal, unknowable, self-sufficient source of life in His existence, He reveals Himself, comes to the one whom He Himself chose and with whom He entered into a Covenant - in order to always be present.

This vivid and illustrative example of the linguistic roots of theological science testifies to the utmost importance of the study of ancient classical languages for the revival of the traditions of theological schools in Russia. The Bible should be fruitfully studied in the context of all church writing, existing in different languages - ancient and modern.

The early Christian community did not have a canonically approved Holy Scripture for several decades, but Christians from the very beginning had their own tradition - an oral tradition, including an extensive collection of stories and testimonies about the life and death on the cross of Jesus Christ, his Resurrection and Ascension, his teaching and ethics. These oral narratives begin to be recorded on parchments and papyri, and so their own Holy Scripture arises - the New Testament, the text of which is also written in Greek - in the Alexandrian dialect of the ancient Greek language (Koine).

So, theology in the first centuries of Christianity arises as a scriptural and exegetical (based on Scripture) experience of understanding the divine-human nature of Jesus Christ, as an experience of the Revelation of this mystery and a form of expression of this Revelation. The Church lived in that era without a developed system of scientific theology (in apostolic times, even such familiar categories of theological thought as the Trinity or the God-Man were absent). However, the first apologetic works and treatises were created in Greek and then Latin (the language of the Roman Empire), in which the authors attempted to substantiate the Christian faith and express the hope of Salvation in Christ.

However, apologetic works of the era of early Christianity often contained a radical rejection of the pagan philosophy of ancient Greek thinkers.

For example, the Christian thinker Quintus Septimius Florence Tertullian (c. 160 - after 220) demanded a categorical rejection of the ancient heritage: “So, what does Athens have to do with Jerusalem? What is the Academy – the Church?”[14].

Tertullian denied the significance of the sophisticated philosophy and dialectics of Plato and Aristotle. From his point of view, a simple, uneducated and uneducated soul is “Christian” by nature, and only a person with such a soul has the opportunity to enter the Kingdom of God. It is not pagan “theology”, but Christian faith that opens the path to Salvation for man.

In his treatise “On the Testimony of the Soul” (“De testimonio animae”, 197), Tertullian proves that the human soul is characterized by Christian virtues and pre-given knowledge of the Creator, the idea of the Last Judgment and the Kingdom of God. The human soul, Tertullian claims, is older than the letter, and “man himself is older than the philosopher and the poet”[15].

However, in the same era, Christian thinkers appeared who emphasized the utmost importance of ancient Greek culture and language for Christian theology. Titus Flavius Clement of Alexandria (150 – 216) was the head of the theological school in Alexandria, which was part of the Roman Empire at that time. Clement of Alexandria was engaged in the “catechumen” of converts before receiving baptism and, thanks to the experience of the catechumenate, he created his own theological system, which was based on a fundamentally different foundation. According to Clement's views, all ancient education was a preparation for the Christian faith. Before Jerusalem on the way to the Kingdom of God is Athens.

Thus, Clement of Alexandria, long before the Cappadocian fathers, defended the concept of the complementarity of culture and cult. It is in his works that the principle is first encountered that philosophy should be the handmaiden of theology. (Accordingly, ancient geometry, astronomy and music should be the “handmaidens” of philosophy).

The study of the patristic heritage of the Church - Christian authors of the East and West - is carried out by such an ecclesiastical scientific discipline as patristics. These church writers had professional philological training, and their works, written in the classical languages of antiquity - Greek and Latin, determined the development of not only Christian theology, but also European and even world science and culture in general.

Presbyter Origen (c. 185 - 253/4), another major representative of the Alexandrian school, despite the existing persecutions in church history, is recognized by church science as the founder of scientific biblical textology: “He studied the Hebrew and Greek texts of the Bible, compared various translations of the Old and New Testaments , using six columns of translations, collected in Alexandria a large number of manuscripts and versions of the texts of the entire Old Testament. Origen left many different interpretations of Holy Scripture to subsequent generations of theologians. In this way he set the tone for further study of Scripture and the very nature of theology. Origen’s main statement is the following: the entire content of Holy Scripture – both the New and Old Testaments – is Christ Himself.”[16]

The theological lexical apparatus and terminology of the Church were initially formed in Greek, which has long been the language of culture - in Italy, Gaul, and Africa. Many authors considered themselves Romans and wrote in Greek (Emperor Marcus Aurelius, Apuleius, etc.). The need for Christian literature in Latin was determined by the increasing number of proselytes outside the Jewish communities. Among them there were many people who did not know Greek. This is how Christian literature in Latin arose (Tertullian, Minucius Felix, Clement of Rome, etc.): “The Latin language of the Christian world is, first of all, the language of the Holy Scriptures and the Church. This means the language of the Vulgate, the language of the Liturgy, the Fathers of the Church before its division - Augustine, Jerome; church writers of the same period - Tertullian, Lactantius, Orosius, Sulpicius. This also includes the language of scholasticism of the first centuries of Christianity and theology of later centuries, the language of the fathers of the Catholic Church, the language of canon law, the language of the decrees of the papal throne from the time of Gregory the Great to Benedict XVI”[17].

Under these conditions, the importance of the work of translators has increased immeasurably. Extremely important translation activities were carried out by Blessed Jerome of Stridon (342–420); he became the creator of the canonical text of the Bible in Latin ("Vulgata" / "Vulgate"). There were other authoritative Latin translations of the Bible, for example, those made in the 2nd century in Africa (Versio Afra) and Italy (Vetus Itala). The version of the Latin translation, owned by Jerome, was verified with the Hebrew text (even the word order of the original was preserved) and is rightfully considered the best.

The greatest Christian thinker and theologian St. Augustine (354–430) wrote in Latin, who created the fundamental theological works of the Church, had a strong influence on the form and style of Western Christian theology and became the founder of the “confessional genre” in the Latin Christian tradition, describing the history own conversion and life in Christ (“Confessionum libri tredecim”, c. 400).

The patristic period of Christian theology covered both Western and Eastern Christian traditions and lasted from the 4th to the 12th centuries. During this era, fundamental theological treatises were created in both Greek and Latin, and the theology of the Ecumenical Councils crystallized.

In the works of such St. Fathers of the Church, such as Saints Athanasius the Great (298–373), Basil the Great (c. 330–379), Gregory the Theologian (329–389), Gregory of Nyssa (c. 335–394), church dogma takes shape, the highest intellectualism develops in combination with revelations of mystical experience and the depth of contemplative sacred silence of mental-heart prayer. And, of course, the essence of the theological disputes of the patristic period was rooted in the problem of expressing authentic Christian teaching in formulas, i.e. had a linguistic nature: “The question of verbal expression is not idle; - emphasized the largest expert on Christian literature S.S. Averintsev, - the stable status of a term may lag behind the awareness of the problem, but the struggle for the term begins with this awareness. Let us remember with what tension, breaking semantic inertia, transforming the previous meaning of the word, Christian dogmatic thought of the 4th century created the term to convey the concept of “hypostasis” it needed. As in general in ancient everyday and philosophical usage, so in the Septuagint (for example, Wis. 16:21), the word “ipostasis” is still extremely far from its future Christian doctrinal meaning. The term “person” in its “personalistic”, philosophical and theological sense is also alien to biblical usage - phrases like “in front of the face” or “face to face” mean something completely, completely different. “Personalist” terminology in Trinitarian disputes (“One God in Three Persons”) has long presented difficulties - that’s why the term “hypostasis” was required.”[18].

The next, Byzantine, period of Christian theology was also full of doctrinal disputes, which, of course, went beyond simply linguistic issues, but also had their roots in the issues of philosophy and theology of language. Theology of Patriarch Photius, dispute of St. Gregory Palamas and Barlaam of Calabria are essentially rooted in the problems of expressibility/inexpressibility of a symbol, utterability/ineffability of language, which has a philosophical and linguistic nature.

Even before the death of Byzantium (XV century), the great heritage of Christian theology and Christian culture through the efforts of the Thessalonica brothers, St. Cyril and Methodius, through the zeal of their followers and disciples, was transferred to the Slavs - through Moravia and Bulgaria - to Rus'. With the adoption of Christianity from Byzantium, Rus' entered into theological, cultural-historical, creative and intellectual interaction with ancient linguocultural traditions and dogmatic concepts. O. Georgy Florovsky in his outstanding book “Ways of Russian Theology” (1937) emphasized the immutable significance of the Cyril and Methodius work: “This was the formation and formation of the “Slavic” language itself, its internal Christianization and churching, the transformation of the very elements of Slavic thought and word, Slavic “logos”, the very soul of the people. The “Slavic” language was formed and strengthened precisely in the Christian school and under the strong influence of the Greek church language, and this was not only a verbal process, but precisely the composition of thought. The influence of Christianity is felt much further and deeper than the actual religious themes, it is felt in the very manner of thought... - So at the beginning of the 11th century in Rus', a whole literature suddenly appeared in circulation in a close and completely accessible language. In essence, the entire written stock of Simeonov’s Bulgaria became and was available to the Russian scribe”[19].

Historians argue about the degree of indirectness of the Greek-Byzantine influence on ancient Russian culture, which was carried out primarily through the South Slavic written tradition, i.e. via Bulgaria. And, indeed, the direct spiritual and cultural meeting with Byzantium and the “Greek element” (Archpriest Georgiy Florovsky) was secondary - after the perception of Bulgarian Christian writing. However, “Bulgarian writing, however, did not overshadow Greek, at least in the 11th century. Under Yaroslav, in any case, in Kyiv (and, it seems, at the St. Sophia Cathedral), a whole circle of translators from Greek was working, and the work of this circle was associated with the entry into Slavic circulation of a long series of monuments unknown in Simeon’s Bulgaria.”[20]

However, in the pre-Mongol period, a theological system did not have time to form in ancient Russian culture, but liturgical, liturgical, and iconographic traditions, firmly connected with translated Greek writing, received powerful development in Russian Orthodoxy of that time. And the main wealth that Russian Orthodoxy, Russian culture as a whole, received in this era was, of course, the Church Slavonic language: “The Church Slavonic language,” noted V.V. Veidle, “raised Russian and eventually merged with it in the new Russian literary language, in its cultural vocabulary, word formation, syntax, stylistic possibilities, there is an exact fragment from the Greek language, much closer to it (not genetically, but in its internal form) than the Romance languages are to Latin”[21].

Since the 17th century in the history of Ancient Rus' there has been a theological encounter with the Western Christian tradition. The need to protect the Orthodox tradition from Catholic and Protestant influences (moreover, highly intellectual and powerful influences: scholasticism, sophisticated theology of the Jesuits, sharply critical rationalism of the ideas of the Reformation) led to the emergence and gradual strengthening of the Russian theological school. The Kiev Academy and the theology developed in it by Peter Mogila were based on the Latin language. The “Slavic-Greek-Latin Academy” that arose in Moscow also based the educational process in Latin and used an experimentally proven scholastic approach. “And yet, finding ourselves on Russian Orthodox soil,” emphasizes Fr. Alexander Schmemann, “the methods of Western theology remained alien to the spirit of Orthodoxy, even if they were perceived by the mind”[22].

Thus, Byzantine and (more broadly, Greek) Christian culture fully passed on their heritage to their closest relatives to the Latin (European) and Slavic peoples. The significance of the Greek language of the Christian Church for Russian Orthodox culture lies in the idea of Logos, perceived by Christianity as the gift of the incarnation of God the Word. The Greek basis of the Russian Word-Logos - evidence and guarantee of its church-dogmatic continuity from Byzantine Orthodoxy - is combined in the history of Russian Orthodox theology with the Latin roots of scholastic theology, which can definitely be considered as a fruitful source of interaction enriching Russian church culture. And the ancient classical languages - the languages of Christian theology - became the cultural soil for the formation and growth of the Slavic peoples, being not just a linguistic compendium of borrowings and influences, but a living embodiment of the traditions of Christian verbal culture - the traditions of the languages of the Holy Scriptures and Holy Tradition, the works of the holy fathers and teachers of the Church .

Bibliography

1. Averintsev S.S. Collected Works / Ed. N. P. Averintseva and K. B. Sigov. Connection of times. – K.: SPIRIT I LITERA, 2005. – 448 p.

2. Veidle V.V. The task of Russia / [with the blessing of Metropolitan of Minsk and Slutsk, Patriarchal Exarch of All Belarus Philaret]. – Minsk: Publishing House of the Belarusian Exarchate, 2011. – 512 p.

3. Glubokovsky N.N. Slavic Bible // Collection in honor of prof. L. Miletich: seven years after birth (1863-1933). – Sofia: Edition at the Macedonian Scientific Institute, 1933, – pp. 333 – 349. https://azbyka.ru/library/slavjanskaja-biblija.shtml

4. Glubokovsky N. N. Russian theological science in its historical development and the latest state. M., 2002. – 192 p.

5. Gorsky-Platonov P.I. A few words about the bishop’s article. Feofan “On the editions of the sacred books of the Old Testament in Russian translation”, M., 1875.

6. Gorsky-Platonov P.I. About Hebrew. manuscripts of the Pentateuch in the 12th century. Slavic Psalter of the 18th century, translated from Hebrew. St. Petersburg, 1880.

7. Gorsky-Platonov P.I. About the perplexities caused by the Russian translation of the sacred books of the Old Testament, art. 1 – 3, M., 1877.

Latin language of the Christian world: textbook. manual / abbot Agafangel (Gagua), L. A. Samutkina, S. V. Pronkina. – Ivanovo: Ivan. state University, 2011.

9. Tertullian K.S.F. Selected works. – M., 1994.

10. Theophan the Recluse (Govorov), St. Regarding the publication of the sacred books of the Old Testament in Russian translation // Soulful Reading, 1875, III. pp. 342-352.

11. Filaret (Drozdov), St. On the dogmatic dignity and protective use of the Greek Seventy Interpreters and the Slavic translations of the Holy Scriptures. 1845. https://orthodox.ru/philaret/nasl_014.php

12. Florovsky, Georgy, archpriest. Paths of Russian theology. – Paris, 1983.

13. Schmemann, Alexander, protopresbyter. Introduction to Theology. Course of lectures on dogmatic theology. Klin: Christian Life Foundation, 2001. – 63 p.

14. Yurevich D. Yu. Prophecies about Christ in the Dead Sea Manuscripts / Priest Dimitri Yurevich. – St. Petersburg: Aksion estin, 2004. – 254 p.

15. Yurevich D.Yu. The Greek translation of the Old Testament by the Seventy Interpreters in the light of the biblical Dead Sea manuscripts. Appendix 1 // Yurevich D. Yu. Prophecies about Christ in the Dead Sea Manuscripts / Priest Dimitry Yurevich. – St. Petersburg: Aksion estin, 2004. pp. 228 – 235.

[1] Schmemann, Alexander, protopresbyter. Introduction to Theology. Course of lectures on dogmatic theology. Klin: Christian Life Foundation, 2001. P. 3.

[2] Ibid. S. 3.

[3] Schmeman, A. Decree. op. pp. 5-6.

[4] Ibid. P. 22.

[5] Gorsky-Platonov P.I. About the perplexities caused by the Russian translation of the sacred books of the Old Testament, Art. 1 – 3, M., 1877; A few words about the bishop’s article. Feofan “On the publication of the sacred books of the Old Testament in Russian translation”, M., 1875; About ev. Manuscripts of the Pentateuch in the 12th century. Slavic Psalter of the 18th century, translated from Hebrew. St. Petersburg, 1880.

[6] Theophan the Recluse (Govorov), St. Regarding the publication of the sacred books of the Old Testament in Russian translation // Soulful Reading, 1875, III. pp. 342-352.

[7] Filaret (Drozdov), St. On the dogmatic dignity and protective use of the Greek Seven Network of interpreters and Slavic translations of the Holy Scriptures. 1845. https://orthodox.ru/philaret/nasl_014.php

[8] Glubokovsky N.N. Slavic Bible // Collection in honor of prof. L. Miletich: seven years after birth (1863-1933). – Sofia: Publication at the Macedonian Scientific Institute, 1933, – pp. 333-349. https://azbyka.ru/library/slavjanskaja-biblija.shtml

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] See: Yurevich D. Yu. Prophecies about Christ in the Dead Sea Manuscripts / Priest Dimitri Yurevich. – St. Petersburg: Aksion estin, 2004. – 254 p.

[12] Yurevich D.Yu. The Greek translation of the Old Testament by the Seventy Interpreters in the light of the biblical Dead Sea manuscripts. Appendix 1 // Yurevich D. Yu. Prophecies about Christ in the Dead Sea Manuscripts / Priest Dimitry Yurevich. – St. Petersburg: Aksion estin, 2004. P. 230.

[13] Ibid. P. 228.

[14] Tertullian K.S.F. Selected works. M., 1994. P. 109.

[15] Ibid. P. 88.

[16] Schmemann, Alexander, protopresbyter. Introduction to Theology. Course of lectures on dogmatic theology. Klin: Christian Life Foundation, 2001. P. 28.

[17] Latin language of the Christian world: textbook. Manual / abbot Agafangel (Gagua), L. A. Samutkina, S. V. Pronkina. – Ivanovo: Ivan. state Univ., 2011. P. 4.

[18] Averintsev S.S. Collected Works / Ed. N. P. Avernitseva and K. B. Sigov. Connection of times. – K.: SPIRIT I LITERA, 2005. P. 16.

[19] Florovsky, Georgy, archpriest. Paths of Russian theology. – Paris, 1983. P. 6.

[20] Ibid. P. 7.

[21] Veidle V.V. The task of Russia / [with the blessing of Metropolitan of Minsk and Slutsk, Patriarchal Exarch of All Belarus Philaret]. – Minsk: Publishing House of the Belarusian Exarchate, 2011. P. 13.

[22] Schmemann, Alexander, protopresbyter. Introduction to theology... P. 47.

Monuments of the Church Slavonic language

The Church Slavonic language has reached us in quite numerous written monuments, but not one of them dates back to the era of the Slavic first teachers, i.e. The oldest of these monuments (except for the recently found tombstone inscription of 993), dated and undated, belong to the century, which means, in any case, separated from the era of the first teachers by at least a whole century and even more, otherwise two. This circumstance, as well as the fact that these monuments, with the exception of a few, bear more or less strong traces of the influence of various living Slavic languages, makes it impossible to imagine the Church Slavonic language in the form in which it appeared in the century. We are already dealing with a later phase of its development, often with very noticeable deviations from the primary state, and it is not always possible to decide whether these deviations depend on the independent development of the Church Slavonic language, or on outside influence. In accordance with the various living languages, traces of whose influence can be indicated in the monuments of the Church Slavonic language, these latter are usually divided into editions.

Pannonian version

The most ancient monuments written in Glagolitic and Cyrillic alphabet belong here:

- Glagolitic monuments

- Kyiv leaflets in.

- Zograf Gospel, beginning c., maybe end c.

- Mariinsky Gospel (from the same time, with some traces of Serbian influence)

- Gospel of Assemani (c., also not without Serbisms)

- Sinai psalter (c.) and prayer book, or Euchologium (c.)

- Collection of Count Claude, or Griagolita Clozianus (c.)

- several small passages (Ohrid Gospel, Macedonian leaflet, etc.;

- Savvin's book, (not without Serbianisms)

- Suprasl manuscript

- Hilandar leaflets or Catechism of Cyril of Jerusalem

- Gospel of Undolsky

- Slutsk Psalter (one sheet)

Bulgarian version

Represents the influence features of the Middle and Modern Bulgarian languages. This includes later monuments of the 12th, 13th, 14th centuries, such as

- Bologna Psalter, late 12th century.

- Ohrid and Slepce apostles, 12th century.

- Pogodinskaya Psalter, XII century.

- Grigorovichev Paremeinik and Triodion, XII - XIII centuries.

- Trnovo Gospel, late 13th century.

- Paterik of Mikhanovich, XIII century.

- Strumitsky Apostle, XIII century.

- Bulgarian nomocanon

- Strumitsky oktoich

- Octoekh Mihanovich, XIII century.

- many other monuments.

Serbian version

Represents the influence of the living Serbian language

- Miroslav's Gospel, late 12th century.

- Volcano Gospel, late 12th century.

- Helmsman Mihanovich, 1282

- Apostle of Sishatovac, 1324

- Explanatory psalter by Branka Mladenovic, 1346

- Khvalov's manuscript, beginning c.

- St. Nicholas Gospel, beginning c.

- The helmsman of the 13th - 14th centuries, described by Sreznevsky,

- many other monuments

Croatian version

written in angular, “Croatian” Glagolitic alphabet; their oldest examples are no older than the 13th - 14th centuries. Their homeland is Dalmatia and mainly the Dalmatian archipelago.

Czech or Moravian version

The monuments are very few in number and small in size. Reflect the influence of the Czech or Moravian living dialect

- Kyiv passages in., Glagolitic

- Prague excerpts - 12th century, Glagolitic

- Reims Gospel of the 14th century, its Glagolitic part

Old Russian translation of the Church Slavonic language

The richest in the number of monuments (all Cyrillic) with obvious traces of the influence of the living Russian language (zh, ch instead of sht, zhd: candle, mezhu; o and e vm. ъ and ь; “polnoglasie”, third person singular and plural . on -t, etc.).

- V.

- Ostromir Gospel 1056 - 1057 (copied, obviously, from a very ancient original)

- 13 words of Gregory the Theologian

- Turov Gospel

- Izborniki Svyatoslav 1073 and 1076

- Pandect Antiochov

- Archangel Gospel 1092

- Evgenievskaya Psalter

- Novgorod menaions 1096 and 1097

- Mstislav Gospel 1125 - 1132

- St. George's Gospel

- Dobrilovo Gospel 1164

- The long series of these monuments ends with printed books of the 16th century, among which the main place is occupied by the Ostrog Bible, which represents almost entirely the modern Church Slavonic language of our liturgical and church books

Slovinsky version

- The Freisingen passages are written in Latin alphabet and originate, according to some, from c. Their language does not have a close connection with the Church Slavonic language and could most likely receive the name “Old Slavonic”.

Finally, we can also point out the Romanian variety of the Church Slavonic language, which arose among Orthodox Romanians.

Who is called an angel? (not to be confused with an angel!)

In Church Slavonic texts you can find the word “aggel”. It is written like an angel, only without a title - a special icon indicating the importance and divinity of the concept. Read more…

New releases - once a week! Follow the updates on our YouTube channel. Upcoming releases:

The series of videos “I love Church Slavonic” was produced within the framework of the project of the ANO “Sheremetev - with the support of the international open pomegranate competition “Orthodox Initiative”.

Literature

- Nevostruev K.I., Mstislav Gospel of the 12th century. Research. M. 1997

- Likhachev Dmitry Sergeevich, Selected works: In 3 volumes. T. 1.3 L.: Artist. lit., 1987

- Meshchersky Nikita Aleksandrovich, History of the Russian literary language,

- Meshchersky Nikita Aleksandrovich, Sources and composition of ancient Slavic-Russian translated writing of the 9th-15th centuries

- Vereshchagin E.M., From the history of the emergence of the first literary language of the Slavs. Translation technique of Cyril and Methodius. M., 1971.

- Lvov A.S., Essays on the vocabulary of monuments of Old Slavonic writing. M., “Science”, 1966

- Zhukovskaya L.P., Textology and the language of the most ancient Slavic monuments. M., “Science”, 1976.

- Khaburgaev Georgy Alexandrovich, Old Church Slavonic language. M., “Enlightenment”, 1974.

- Khaburgaev Georgy Aleksandrovich, The first centuries of Slavic written culture: The origins of ancient Russian literature M., 1994.

- Elkina N. M. Old Church Slavonic language. M., 1960.

- Hieromonk Alipy (Gamanovich), Grammar of the Church Slavonic language. M., 1991

- Hieromonk Alipiy (Gamanovich), A manual on the Church Slavonic language

- Popov M. B., Introduction to the Old Church Slavonic language. St. Petersburg, 1997

- Tseitlin R. M., Vocabulary of the Old Church Slavonic language (Experience in the analysis of motivated words based on data from ancient Bulgarian manuscripts of the X-XI centuries). M., 1977

- Vostokov A. Kh., Grammar of the Church Slovenian language. LEIPZIG 1980.

- Sobolevsky A.I., Slavic-Russian paleography.

- Kulbakina S.M., Hilandar sheets - an excerpt of Cyrillic writing of the 11th century. St. Petersburg 1900 // Monuments of the Old Church Slavonic language, I. Issue. I. St. Petersburg, 1900.

- Kulbakina S. M., Ancient Church Slavic language. I. Introduction. Phonetics. Kharkov, 1911

- Karinsky N., Reader on the Old Church Slavonic and Russian languages. Part one. The most ancient monuments. St. Petersburg 1904

- Kolesov V.V., Historical phonetics of the Russian language. M.: 1980. 215 p.

- Ivanova T. A., Old Church Slavonic: Textbook. SPb.: Publishing house St. Petersburg. Univ., 1998. 224 p.

- Alekseev A. A., Textology of the Slavic Bible. St. Petersburg. 1999.

- Alekseev A. A., Song of Songs in Slavic-Russian writing. St. Petersburg. 2002.

- Birnbaum H., Proto-Slavic language Achievements and problems in its reconstruction. M.: Progress, 1986. - 512 p.

General articles and books

- Church Slavonic language in the worship of the Russian Orthodox Church. Collection / Comp. N. Kaverin. - M.: "Russian Chronograph", 2012. - 288 p.

- A. Kh. Vostokov, “Discourse on the Slavic language” (“Proceedings of Moscow. General Amateur Russian Words.”, Part XVII, 1820, reprinted in “Philological Observations of A. Kh. Vostokov”, St. Petersburg, 1865 )

- Zelenetsky, “On the Church Slavonic language, its beginnings, educators and historical destinies” (Odessa, 1846)

- Schleicher, “Ist das Altkirchenslavische slovenisch?” (“Kuhn und Schleichers Beitra ge zur vergleich. Sprachforschung”, vol. ?, 1858)

- V.I. Lamansky, “The Unresolved Question” (“Journal of Min. Nar. Prosv.,” 1869, parts 143 and 144);

- Polivka, “Kterym jazykem psany jsou nejstar si pamatky cirkevniho jazyka slovanskeho, starobulharsky, ci staroslovansky” (“Slovansky Sbornik”, published by Elinkom, 1883)

- Oblak, “Zur Wurdigung, des Altslovenischen” (Jagic, “Archiv fu r slav. Philologie”, vol. XV)

- P. A. Lavrov, review citations. above Jagic's research, “Zur Entstehungsgeschichte der kirchensl. Sprache" (“News of the department of Russian languages and words. Imperial Academic Sciences”, 1901, book 1)

Grammarians

- Natalia Afanasyeva. Textbook of Church Slavonic language

- Dobrovsky, “Institution es linguae slavicae dialecti veteris” (Vienna, 1822; Russian translation by Pogodin and Shevyrev: “Grammar of the Slavic language according to the ancient dialect”, St. Petersburg, 1833 - 34)

- Miklosic, “Lautlehre” and “Formenlehre der altslovenischen Sprache” (1850), later included in the 1st and 3rd volumes, will compare it. grammar of glory. languages (first edition 1852 and 1856; second edition 1879 and 1876)

- Schleicher, "Die Formenlehre der Kirchenslavischen Sprache" (Bonn, 1852)

- Vostokov, “Grammar of the Church Slavic language, presented according to the oldest written monuments thereof” (St. Petersburg, 1863)

- his “Philological. observations" (St. Petersburg, 1865)

- Leskin, “Handbuch der altbulgarischen Sprache” (Weimar, 1871, 1886, 1898

- rus. translation by Shakhmatov and Shchepkin: “Grammar of the Old Church Slavonic language”, Moscow, 1890)

- Greitler, “Starobulharsk a fonologie se stalym zr etelem k jazyku litevske mu” (Prague, 1873)

- Miklosic, “Altslovenische Formenlehre in Paradigmen mit Texten aus glagolitischen Quellen” (Vienna, 1874)

- Budilovich, “Inscriptions of Ts. grammar, in relation to the general theory of Russian and other kinships. languages" (Warsaw, 1883); N. P. Nekrasov, “Essay on the comparative doctrine of the sounds and forms of the ancient Church Slavs. language" (St. Petersburg, 1889)

- A. I. Sobolevsky, “Ancient Church Slav. language. Phonetics" (Moscow, 1891)

Dictionaries

- Vostokov, “Dictionary of the Central Language” (St. Petersburg, 2 vols., 1858, 1861)

- Miklosic, “Lexicon palaeosloveuico-graeco-latinum emendatum auctum...” (Vienna, 1862 - 65). For etymology, see title. Miklosic's dictionary and in his “Etymologisches Worterbuch der slavisc hen Sprachen” (Vienna, 1886).

Used materials

- Brockhaus and Efron, article Church Slavonic language

- Encyclopedia "Around the World", article "Church Slavonic language"

- A.Yu. Musorin, Church Slavonic language and Church Slavonicisms, Science. University. 2000. Materials of the First Scientific Conference. - Novosibirsk, 2000. - P. 82-86

- Larisa Marsheva, PRASLAVIAN, CHURCH SLAVIC, RUSSIAN...,

[1] Khaburgaev G.A. Old Slavonic language. Textbook for pedagogical students. Institute, specialty No. 2101 “Russian language and literature”. M., "Enlightenment", 1974

[2] N.M. Elkina, Old Church Slavonic language, textbook for students of philological faculties of pedagogical institutes and universities, M., 1960