Throughout its two centuries of existence, the Christian Church has proven its faithfulness to God. The best proof is human life. Neither theological works, nor beautiful sermons, nothing proves the truth of religion more than a person who is ready to give his life for its sake.

Living in the modern world, where everyone can freely profess their faith and express their opinion, it is difficult to imagine that just a hundred years ago this could lead to execution. The 20th century left a bloody trail in the history of Russia and the Russian Church that will never be forgotten and will forever remain an example of what the state’s attempt to gain total control over society can lead to. Thousands of people were killed simply because their faith was not acceptable to the authorities.

Who are the New Martyrs and Confessors of Russia

The main Christian denomination of the Russian Empire is Orthodoxy. After the 1917 revolution, members of the faith were among those subjected to communist repression. It was from these people that the host of saints subsequently came, which is a treasure for the Orthodox Church.

Origin of words

The word "martyr" is of ancient Greek origin (μάρτυς, μάρτῠρος) and is translated as "witness". Martyrs have been revered as saints since the beginning of Christianity. These people were firm in their faith and did not want to renounce it even at the cost of their own lives. The first Christian martyr was killed around 33-36 (First Martyr Stephen).

Confessors (Greek: ὁμολογητής) are those people who openly confess, that is, testify to their faith even in the most difficult times, when this faith is prohibited by the state or does not correspond to the religious belief of the majority. They are also revered as saints.

Meaning of the concept

Those Christians who were killed in the 20th century during political repression are called new martyrs and confessors of Russia.

The martyrdom is divided into several categories:

- Martyrs are Christians who gave their lives for Christ.

- New martyrs (new martyrs) are people who suffered for their faith relatively recently.

- Hieromartyr - a person in the priestly rank who accepted martyrdom.

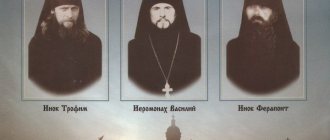

- A venerable martyr is a monk who accepted martyrdom.

- A great martyr is a martyr of high birth or rank who has endured great torment.

For Christians, accepting martyrdom is a joy, because by dying, they are resurrected for eternal life.

Theory and practice

If the New Martyrs had been engaged in “practice” and not theory, that is, if they had been told: stop serving the Services, go work for the common good, then they would have rolled up their sleeves and built a new life, working as an agronomist or accountant. They would not have built a new life, but they would have preserved the temporary one, for a long time or for a short time. However, Vera’s theoretical reasoning: “I am a priest, I swore an oath to the Invisible God to serve Him until death - and therefore I do not dare agree” - did not allow the priest to practically, that is, insanely, take this path of betrayal of Faith and grace.

So, all the New Martyrs were theorists - and this is what cost them their lives.

Before they were arrested and shot, they mentally decided to do this. They decided when they had not yet been shot at.

That is, in a theory that is obligatory for them. In abstract speculation applied to oneself as an individual.

That is, theoretically, not practically. For “practically” the person does not exist.

In practice – as Lenin said, “in sensations” – matter exists. But she is seen only as a verbal personality, capable of seeing with her mind, which Lenin does not know about.

The personality itself is the mind. This is how it was created by God, this is how the Church teaches about it.

To think using innate concepts is to theorize.

A Christian, applying in his thinking not only innate concepts, but also the revealed dogmas of Faith, is a gracious judge of both nature and time. Unpractical and disinterested - and therefore not subject to their control.

Those former Christians who in our time propagate the false theory: “Christianity is not a theory, but a practice” - provide a theoretical basis for retreat. In fact, what prevents them, having left the Service, to organize gala concerts or do business. Practice doesn't hurt. Practice, that is, fallen nature, wordlessly says: this is the same, because you are the same. Your nature is the same. You love everyone the same way, “stay with everyone.” Your existence does not change because you are developing and moving.

Theory gets in the way. It doesn't allow you to move. She is chained to the chopping block.

Those who are tolerant of Konanos and Fedosov will not pray to the martyred for refusing to be defrocked.

New Martyrs of Russia

After the Bolsheviks came to power, their main goal was to preserve it and eliminate their enemies. They considered enemies not only to structures directly aimed at overthrowing Soviet power (the White Army, popular uprisings, etc.), but also to people who did not share their ideology. Since Marxism-Leninism presupposed atheism and materialism, the Orthodox Church, as the largest, immediately became their opponent.

Historical reference

Since the clergy had authority among the people, they could, as the Bolsheviks thought, incite the people to overthrow the government, and therefore pose a threat to them. Immediately after the October uprising, persecution began. Since the Bolsheviks were not completely strengthened and did not want their government to look totalitarian, the elimination of representatives of the Church was not determined by their religious beliefs, but was presented as punishment for “counter-revolutionary activities” or for other fictitious violations. The wording was sometimes absurd, for example: “he delayed the church service in order to disrupt field work on the collective farm” or “he deliberately kept small silver coins in his possession, with the goal of undermining the correct circulation of money.”

The rage and cruelty with which innocent people were killed sometimes exceeded that of the Roman persecutors in the first centuries.

Here are just a few such examples:

- Bishop Feofan of Solikamsk was stripped in front of the people in the bitter cold, tied a stick to his hair and lowered into an ice hole until he was covered with ice;

- Bishop Isidore Mikhailovsky was impaled;

- Bishop Ambrose of Serapul was tied to the tail of a horse and allowed to gallop.

But most often, mass execution was used, and the dead were buried in mass graves. Such graves are still being discovered today.

One of the places for execution was the Butovo training ground. 20,765 people were killed there, 940 of them were clergy and laity of the Russian Church.

List

It is impossible to list the entire council of new martyrs and confessors of the Russian Church. According to some estimates, by 1941, about 130 thousand clergy were killed. By 2006, 1,701 people had been canonized.

This is just a small list of martyrs who suffered for the Orthodox faith:

- Hieromartyr Ivan (Kochurov) - the first of the murdered priests. Born July 13, 1871. He served in the USA and conducted missionary activities. In 1907 he moved back to Russia. In 1916 he was appointed to serve in the Catherine Cathedral of Tsarskoye Selo. On November 8, 1917, he died after prolonged beatings and dragging along railroad sleepers.

- Hieromartyr Vladimir (Epiphany) - the first of the murdered bishops. Born January 1, 1848. Was Metropolitan of Kyiv. On January 29, 1928, while in his quarters, he was taken out by sailors and killed.

- Hieromartyr Pavel (Felitsyn) was born in 1894. He served in the village of Leonovo, Rostokinsky district. He was arrested on November 15, 1937. Accused of anti-Soviet agitation. On December 5, he was sentenced to 10 years of work in a forced labor camp, where he died on January 17, 1941.

- Reverend Martyr Theodosius (Bobkov) was born on February 7, 1874. His last place of service was the Church of the Nativity of the Virgin Mary in the village of Vikhorna, Mikhnevsky district. On January 29, 1938 he was arrested and executed on February 17.

- Hieromartyr Alexy (Zinoviev) was born on March 1, 1879. On August 24, 1937, Father Alexy was arrested and imprisoned in the Taganskaya prison in Moscow. He was accused of holding services in people's homes and conducting anti-Soviet conversations. On September 15, 1937 he was shot.

It should be noted that during interrogations they often did not admit to what they did not do. They usually said that they were not involved in any anti-Soviet activities, but this did not matter because the interrogations were purely formal.

Speaking about the martyrs of the 20th century, one cannot fail to mention St. Tikhon, Patriarch of Moscow (January 19, 1865 - March 23, 1925). He is not glorified among the martyrs, but his life was a martyr because the patriarchal service fell on his shoulders in these difficult and bloody years. His life was full of difficulties and suffering, the greatest of which was knowing that the Church entrusted to you was being destroyed.

The family of Emperor Nicholas is also not canonized as martyrs, but for their faith and dignified acceptance of death, the Church honors them as holy passion-bearers.

The revolution is within us

However, this is the deep leaven of the revolution: when people begin to consider themselves masters on earth, creators and authors of their own and others’ destinies. And this is not only the similarity between the Bolsheviks and the new Russians, between the renovationists of the 1920s and modern modernists.

We ourselves have the undestroyed leaven of faith in ourselves, faith in people, faith in the future. Faith in ideals, determination. Striving for the “goal” instead of standing still in faith and incessantly thirsting for salvation.

This romantic belief in earthly things did not begin with us. Already Tyutchev said: “You can only believe in Russia.” Tsar-Martyr Nicholas II did not say this, and even less so Alexei Mikhailovich, the Quiet Tsar. He did not believe in Russia, he believed in the Lord God. The Tsar loved Russia and sacrificed himself for it. And that's enough. Likewise, it is enough to love your neighbors: your father and mother, and your neighbors. And to believe only in the Lord God. And when people begin to believe in themselves, in other people, in the people, in earthly goodness, in ideals - and we are fermented with this from childhood - then “feats and achievements” begin. Starting with sporting successes and victories, when “we firmly believe in the heroes of sports, we need victory like air” - and ending with the achievement of goals in a career, in business, in politics, in our own destiny.

Quote from Maxim Gorky at the clinic of the Blokhin Russian Cancer Research Center. Moscow, 2021.

And the worst thing is that under this consciousness the Christian Faith is made up in our minds. That she, too, becomes, alas and alas, a support for these earthly accomplishments, these goals and objectives - personal and social. In this we are children of the revolution.

“Trust in God in trials, be patient in suffering,” we hear in the stichera to the Martyr Tsar.

What does optimism, self-confidence, struggle with difficulties, and the pursuit of goals have to do with it?

- Nothing.

The prayer to the New Martyrs would be effective if we followed their path - the path of conflict with the same Revolution. But freedom, equality, fraternity, democracy, human rights, faith in a bright future, the doctrine of the fundamental equality of people of all faiths and religions, the equality of faith and unbelief, the doctrine of universal suffrage - equal rights of men and women, fathers and children, evil and good - we consider all this today to be our property, although this is the teaching of the French and Russian revolutions. The doctrine of universal fundamental values is the totalitarian doctrine of modern civilization. It is present not only in popular revolutionaries: priest Gapon, archpriest Vinarsky.

Archpriest Andrei Vinarsky at a rally in support of Sergei Furgal. Khabarovsk, 2021.

It is present in us, and the modern world does not forgive us for abandoning it.

Day of Remembrance of the New Martyrs and Confessors of Russia

Even at the bishops' council of 1817-1818. decided to commemorate all the deceased who suffered in persecution. But at that time they could not canonize anyone.

The Russian Orthodox Church Abroad was the first to take a step towards their glorification on November 1, 1981, and set the date of celebration on February 7, if this day coincides with a resurrection, if not, then on the next Sunday. In Russia, their glorification took place at the Council of Bishops in 2000.

Celebration traditions

The Orthodox Church celebrates all its holidays with the Holy Liturgy. On the day of the celebration of St. This is especially symbolic of martyrs because during the Liturgy the sacrifice of Christ is experienced, and at the same time the sacrifice of the martyrs who gave their lives for Him and for the holy Orthodox faith is remembered.

On this day, Orthodox Christians remember with bitterness those tragic events when the Russian land was soaked in blood. But the consolation for them is that the 20th century left the Russian Church with thousands of holy prayer books and intercessors. And when they are asked who the new martyrs are, they can simply show old photographs of their relatives who died in persecution.

The revolution continues

The time with which the currently celebrated saints entered into contradiction and insoluble conflict has not gone away. It continues. This is all the same, the so-called New Time - the time of revolution, the time of reformation, the time of the Enlightenment, the time of that ideological totalitarianism that will lead to the Antichrist. It began in the 16th century, when man became liberated and became an independent entity on earth instead of standing before the Lord God. If we say that our time is completely different, safe for the Church, then we are moving with this time in its general flow and direction and therefore do not feel discomfort.

Yes, that is right.

We did not break with the Revolution, with its earthly faith: the desire for progress, with faith in the future, in ourselves, in people. With a faith in which there is nothing Christian.

The ideals of the New Age, the ideals of the Reformation and Enlightenment: personal freedom, democracy, the human right to sin - in a word: the global values of modern civilization - are present in us. It was these ideals of both the French and Russian Revolutions that brought the Christians who rejected them to the chopping block.

The non-condemnation by the church authorities of the ideology of Sergianism, that is, the fundamentally approved “co-laboration” with any available state power is not, therefore, the exclusive reason for the disrespect of the New Martyrs. The reason is broader. It is in our inner union with time, in that union that the New Martyrs rejected. Not only those who rejected the Declaration, but everyone who came into conflict with the era, costing them their lives.

These Christians, who never turned the tide of time, seem too weak to modern people.

Or, on the contrary, proud people who were afraid to get dirty by keeping up with the times and missed the opportunity - as many believe and think deep down - to influence this time. Instead of, even if sinning over time, “doing a lot” and thereby transforming the situation around you and the time itself. Achieve noticeable results.

Left with nothing?

If we really give up these sprouts and even the fruits of revolution in our souls, then what will we be left with? In fact, with nothing, it’s as if we are abandoning ourselves. Let's stop believing in ourselves, in our life goals, believing in success and striving for it. We will stop believing in progress, in science, in the future. We will stop believing in people, in the nation, in Russia. What will be left of us then?

What will remain - if it exists - is what our pious ancestors, the old Russians, had. They had no trace of any of this, they didn’t believe in any success, they didn’t believe in any future. They did not believe in any people. They didn’t believe in Russia either. No one like God! This is their faith. On the contrary, they knew that all the good things were in the past; they only wanted to save the soul. They loved their people, but they did not create illusions. And they did not consider themselves the architects of their own happiness.

Who did not spare his own Son, but gave him up for us all, how then should he not also give us all things with him? (Rom. 8:32) - this is what they hoped for when they got married, when they raised children, when they built temples and decorated them. When they went to die for the Tsar.

For this internal order, for this complete dedication and humility, the Lord gave earthly beauty, earthly wealth and earthly victory in battles.

Report by A.L. Beglova, Ph.D. n., at the VI International Theological Conference of the Russian Orthodox Church on the topic “Life in Christ: Christian morality, the ascetic tradition of the Church and the challenges of the modern era.”

The Russian Church has been enriched by a large number of martyrs and confessors during the long-suffering twentieth century. Their feat, without a doubt, is worthy of becoming one of the central themes of theological understanding of modern religious and philosophical thought. The author of the report reflects on the possible directions of this vector of comprehension.

The twentieth century became a time of martyrdom and confessional feat of the Russian Church. The scale of the martyrdom - as many contemporaries noted - is comparable to the era of martyrdom in the first centuries of the Christian era. The image and experience of the martyrs of this period, the new martyrs and confessors of Russia should have become (but has not yet become) one of the central themes of theological understanding of today's Russian theological and religious-philosophical thought. In this report we want to offer some reflections from a historian about the direction in which this understanding might move.

“Victims” or “heroes”: understanding the feat of the new martyrs in modern literature

As we said, the comparison of Russian new martyrs and martyrs of the first centuries is quite common. Along with this, attention was drawn to the significant difference between these phenomena. The martyrs of the first centuries were and were preserved in church tradition as witnesses of faith and resurrection, who, being faced with a choice - faith in Christ and death or renunciation of Him and preserving life - chose faith and being with the Savior and thereby testified to the truth of His resurrection. In contrast, the martyrs of the twentieth century were often deprived of any possibility of choice. As representatives of groups subject to social segregation, they were doomed to be deprived of their civil rights and then their lives. In the overwhelming majority of cases, no one offered them to save their lives at the cost of renouncing their faith[1]. They turned out to be not witnesses, but victims. In this regard, one can recall the aphorism of Varlam Shalamov, who said that in Stalin’s camps there are no heroes, but only victims.

If this is so, then what was the feat of the new martyrs? Do we really only honor them as victims, like the innocent (and unconscious) infant martyrs of Bethlehem, “who were killed only because God became man”? The literature suggested understanding the inevitable martyrdom of the Soviet period as evidence not of the resurrection, but of Golgotha, i.e. evidence of the human nature of Christ, which was reflected in His death, in contrast to the Divine nature, expressed in His resurrection, to which early Christian martyrs testified[2]. In this interpretation, the new martyrs turn out to be a small part of the innocent victims during the years of political repression, separated from this countless host, so to speak, on a confessional basis. Meanwhile, upon closer examination, such a reading of the feat of the new martyrs raises questions: by the beginning of the Soviet experiment, the entire country had been baptized, and why not then glorify, at least as passion-bearers, all the dispossessed and exiled peasants. Obviously, the victim paradigm blurs the understanding of martyrdom.

On the other hand, in literature there is a tendency to understand the martyrdom of the Soviet period precisely as heroism, as a feat of resistance to Soviet power[3]. But in order to fill such an understanding of the martyrdom of the twentieth century. specific content, we have to make a certain intellectual and historical reduction. First of all, the focus of this interpretation is on church movements and personalities that quite clearly demonstrated their political opposition to the existing regime, primarily the so-called “catacomb” movements. If such opposition did not manifest itself clearly enough, church opposition to the hierarchy of the Russian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate was taken as a sign of resistance to the regime. In this interpretation of martyrdom, church phenomena are systematized within the framework of a binary opposition: resistance vs. collaborationism. Church oppositionists turned out to be heroes of resistance, and clergy and laity who remained faithful to the clergy, regardless of their position in life and death, found themselves under suspicion of conniving with the regime.

Meanwhile, the historical reality is more complex. Even the oppositionists were not always disloyal to the existing regime. In addition, adhering to this paradigm, we ignore the martyrdom of the rest, the non-opposition part of the Patriarchal Church, which numerically, in terms of the number of parishes, exceeded the opposition movements. Qualifying her position as collaborationism is about the same as accusing dispossessed peasants driven into collective farms of collaboration. In addition, it is necessary to take into account the conciliar decision of the Church, which, in glorifying the new martyrs, considered it right not to separate the martyrs who were faithful to the hierarchy and the moderate oppositionists who maintained prayerful unity with Metropolitan. Peter (Polyansky).

Thus, the paradigm of new martyrs as victims blurs the understanding of martyrdom, and the paradigm of martyrs as oppositionists, dissidents narrows, and most importantly distorts, our understanding of this phenomenon, overly emphasizing the church-political aspect of church history of the twentieth century. Both of these approaches cannot satisfy us. It seems that we can find the key to a different understanding of the phenomenon of the new martyrs by turning to the consideration of the features of Soviet repressive policy.

The feat of the new martyrs in the light of the peculiarities of Soviet repressive policy

Mass repressions of the 1920s–1950s with their arrests, camps and executions, were only the tip of the iceberg of Soviet repressive policies, which were based on mass social segregation.

Segregation by class was the official policy of Soviet Russia from 1918 to 1936, enshrined in the first constitutions. Then entire categories of residents of the Soviet republic were deprived of civil rights, primarily passive and active suffrage. Among these categories were former nobles, former large property owners, clergy, representatives of the army and police of the old order, and from the beginning of the 1930s. - and dispossessed peasants. Deprivation of civil rights, inclusion in the category of “disenfranchised” for these people was only the beginning of the trials, since it was they who fell under the skating rink of increased taxation, it was they who were primarily subject to eviction from large cities during their “cleansings”, their children were deprived of the right to higher education, they were deprived of access to a centralized food supply during the existence of the rationing system, which actually meant doomed to starvation; they, in the end, were primarily among the politically unreliable and, therefore, candidates for political repression.

Since 1936, the category of deprived people was formally abolished, but social segregation actually continued to be the norm of Soviet policy in subsequent decades. Along with the openly declared class segregation, there was a secret, but generally known to all residents of the country, segregation on other grounds. Among them were: religious affiliation, membership in what was considered an unreliable national (Poles, Latvians, Germans, etc.) or local group (“Harbin people”[4]), membership in socially marked and deviant groups (previously convicted, homeless, prostitutes...) .

Moreover, all this was precisely social segregation, since a person was classified into one or another disadvantaged category not on the basis of his proven criminal acts, but on the basis of “registration” (profile) data or characteristic features of his behavior (going to church, begging... ). Only formal membership in one or another group of the population, which was currently qualified as enemy, was sufficient grounds for execution during numerous “mass operations” of the OGPU-NKVD (kulak, officer, various national, etc.).

What can a look at Soviet repressive policies as a policy of mass social segregation give us to understand the feat of the new martyrs? Quite a lot, I think. Believers were one of the main categories of the population subjected to various oppressions. Of course, the main blow of the segregation policy of the Soviet government fell on the clergy and monastics, but ordinary believers also found themselves under constant pressure. An obvious church position was fraught with serious complications at work and at home, especially in communal apartments; it certainly resulted in obstacles to career growth; believers could be subject to pressure from the Komsomol, social activists or other organizations engaged in anti-religious propaganda. Changes in the work schedule at production (five-day and ten-day) made it impossible to visit churches on Sundays. Ultimately, contacts with the clergy could become a reason for accusing ordinary believers of participating in “anti-Soviet organizations” and making them the target of repression.

In this situation, the continuation of ordinary, everyday religious life became a feat and meant that those who continued to live church life made a conscious and very difficult choice in those conditions. This choice meant making a small or a more significant sacrifice, and - importantly - a willingness to make an even greater sacrifice. If the clergy, monastics, and often members of the parish administration were doomed, then many ordinary parishioners really chose between faith, which promised danger, and silent, unspoken, but still renunciation. The everyday choice in favor of faith, made by the masses of believers, supported the clergy and hierarchy, gave life to the Church, and thanks to it, despite all the efforts of the authorities, the country continued to belong to Christian civilization.

In other words, if hundreds of thousands of hierarchs, priests and believers accepted death, then millions were ready to do so. Life in Christ became the main value for them. For the sake of its preservation, they were ready to endure minor and major oppression, to expose themselves to minor and significant dangers. Thus, when comprehending the feat of the new martyrs, we must shift attention from execution and death to the circumstances of their lives, to that ordinary, everyday feat of them and their loved ones that preceded their arrest. The arrest in this case turned out to be the logical conclusion of their life.

The suffering and glorified new martyrs and confessors of Russia in this case turn out to be a kind of vanguard of many, many believers who, in their place and by virtue of their calling, remained faithful to the Church and the Savior in their daily lives. The life experience of the new martyrs turns out to be the quintessence of the experience of all the faithful of the Russian Church of this period. This means that by honoring the new martyrs, we honor the feat of all Russian Christians of the twentieth century, who were not afraid to continue to live in Christ in militantly anti-Christian conditions.

Moreover, such a view does not mean a new erosion of the understanding of martyrdom, as was the case with the “victim paradigm,” but it means finding new boundaries of this phenomenon. These boundaries are determined by the discovery of real Christian practices in the life of the believer, whom we venerate in the guise of the new martyrs and confessors of Russia. His actions, preserved by documents and church tradition, distinguish him from the ranks of his contemporaries. In addition, in our reading of the phenomenon of new martyrdom, the perception of martyrdom as heroic behavior is preserved, only this heroism is not political at all, but ordinary, everyday [5].

Thus, understanding the feat of the new martyrs as a feat of continuing life in Christ, we must pay closer attention to the characteristics of this life, to its real circumstances. And it turns out that we find ourselves in front of a wide field in which there are the most diverse manifestations of everyday Christian achievement. It seems that these forms of Christian life, characteristic of the era of new martyrdom, can be divided into three categories. Firstly, we can talk about new forms of social and church structure created by this era. Secondly, about the new life practices of Christians, updated by persecution. Finally, thirdly, about the intellectual response given by the generation of martyrs and confessors to the challenges of their time. All this can be understood as the experience of the new martyrs and confessors of Russia. Let us try to briefly characterize each of these categories in the light of the achievements of recent historiography.

Church and social activity

The turn of the 1910–1920s. became a time of rapid growth of church and public associations (brotherhoods, various circles and parish unions, unions of parishes). All this happened against the backdrop of an upsurge in parish life itself, intensified work with young people, charitable activities of parishes, etc. Moreover, this growth of church-social movements occurred at different levels: not only, for example, parish and inter-parish brotherhoods arose, but also unions of brotherhoods and parishes, which coordinated their activities, usually within the city or diocese[6].

The reason for the emergence of such an unusual phenomenon in those conditions - as it seems at first glance -, as it seems to us, was a combination of three factors: the disappearance of bureaucratic control over church life with the fall of the synodal system, the beginning of persecution by the Soviet authorities, which caused a lively rebuff from the believers, who stood up to defend church property, support for this movement from below from the hierarchy and personally from Patriarch Tikhon. (Interestingly, the parish council legislation of 1917–1918 had virtually no influence on this process.)

The largest and fairly well described among such associations was the Alexander Nevsky Brotherhood in Petrograd, which arose in 1918 and existed in one form or another until the early 1930s. It began its activities by protecting the Petrograd Lavra from encroachments by the new government, but soon expanded its activities to church education, work with children and disadvantaged sections of the urban population, and charitable activities. Within the framework of the Alexander Nevsky Brotherhood, several theological circles operated, and even two secret monastic communities were formed within it. In Moscow at the beginning of 1918, on the initiative of the priest Roman Medved, the St. Alexeevsky Brotherhood arose, which set as its task the training of “preachers from among the laity” to protect “the faith and church shrines.” There were many others (in Petrograd alone by the early 1920s there were about 20 of them) in various parts of the country, most of whom we know only by name.

The activities of these associations are striking in their versatility: education, charity, preservation of ascetic tradition (monastic communities). A noticeable feature of this movement was not purely lay (although it was laymen who made up the majority of members and active figures of the fraternities), but its church character, since their main leaders and inspirers were representatives of both the white and monastic clergy. Many church and public associations maintained close contact with the hierarchy and large spiritual centers, not only the Alexander Nevsky Lavra, but also, for example, with the New Jerusalem Resurrection Monastery, with the elders of the St. Smolensk Zosimova Monastery, etc.

It seems that the mentioned church-public associations demonstrate a new nature of the combination of individualism and community. Their growth took place primarily in large cities, i.e. out of connection with the traditional rural community environment, which was at the same time a parish environment, and it was the rural community that was then the main “social base” of the Russian Church. Here church and social movements successfully and very intensively mastered the new social environment. And this happened - let us remind you - precisely in response to the persecution that had begun. Church and social movements at the turn of the 1910s–1920s. were the embryo of a new parish life, which was not destined to develop due to repression.

The experience of the life of the new martyrs in terms of church and social order is the experience of self-sacrifice for the sake of protecting church property, the experience of the broadest mutual assistance (both material and intellectual, expressed in circle self-education, etc.), the experience of this help going beyond the boundaries of their communities (in education and in working with vulnerable social groups)[7].

Daily Life Practices

In recent years, the life practices of twentieth-century Christians have been studied quite intensively. And in the light of our understanding of the feat of the new martyrs, this line of research is extremely important. After all, it is the study of life practices that will help us answer the questions: what exactly was done to preserve church life, what was considered especially important in light of this, and what was less important?

However, we should make one significant caveat here. Before we begin to analyze the behavior and daily practices of the new martyrs, it is necessary to make sure that we are actually dealing with practices determined by religious, and not other social, economic or political motives. Historians of the Soviet period have made quite a lot of observations that resistance to Soviet power on the part of the peasants - either during the Civil War or during collectivization - acquired religious forms, or religious justifications. S. Fitzpatrick also pointed out that the close attention of collectivized peasants in the 30s. to the celebration of even the most insignificant church holidays (of which in some areas there were up to 180 per year) “represented a form of resistance (sabotage of work) rather than a testimony of piety”[8]. Therefore, each time it is necessary to examine a specific case of manifestation of religiosity, and only after research by historians will it be possible to give a theological qualification of this or that phenomenon. To avoid falling into such a trap, I will mention only those practices whose motivation has been sufficiently studied.

Using the example of several monastic and mixed (consisting of monks and laymen) communities (both faithful to the hierarchy of the Russian Church and moderately oppositional), we can identify the following behavioral strategies[9]. First of all, we should mention the everyday disguise of one’s own monasticism or even churchliness. It could include a wide variety of components: from avoiding some features in clothing (everything that would indicate monasticism, black scarves, too long skirts, etc.) to a deliberate silence about everything that could indicate churchliness, or avoidance of the cross signs in public places.

Another important point was the attitude towards secular (Soviet) work. Within the framework of this behavioral paradigm, mentors demanded from monastics or lay people an exceptionally thorough, conscientious attitude to their work. The motive for this attitude was either Christian conscientiousness itself, or the perception of Soviet work as monastic obedience (for monks), i.e. as work performed for God and for one’s monastic community.

In this choice of work itself, and in any relationship with Soviet everyday life in general, there was a principle at work that we could designate as the principle of ascetic pragmatics. According to him, what is permissible is what allows one to maintain the correct spiritual attitude or the purity of the Christian conscience. For example, one of the spiritual leaders of the 1930s, now glorified as a new martyr, advised his students to avoid working in factories or large enterprises, since the atmosphere there could harm the spiritual mood of his charges.

The consequence of this behavioral strategy was a paradoxical phenomenon. Its bearers faced favorable prospects for socialization in Soviet society. In fact, it was about enculturation, the entry of members of these communities into the social and cultural environment around them. Of course, this process - in addition to ascetic pragmatics - had other limitations. It is clear, for example, that Christians could not be members of the Communist Party or Komsomol, which limited their chances of a successful career. But this did not change their own position regarding the social environment. It was possible to preserve spiritual life, life in Christ, only by continuing to live and in conditions that were in no way intended for it. The noted strategies of everyday behavior worked to achieve this super task.

The strategy of inculturation of the new martyrs, entering into the social and cultural environment reveals to us another important feature of their experience. The environment of the Soviet city had too little in common with the traditional Orthodox way of life, so characteristic of pre-revolutionary Russia. However, as we have seen, this did not deter the new martyrs. They entered this non-Christian and churchless environment as if into a “cave burning with fire” and continued to remain Christians in it, transforming it from the inside. The forms of life receded into the background, and it was remembered that Christianity can remain alive and active in any form. This is another aspect of the feat of the new martyrs, showing that they keenly experienced the universality of the Good News. The Russian Church has been much accused of adhering to national forms of Christianity, but the experience of the new martyrs and confessors of Russia shows that for them it was the universality of Christianity that became extremely relevant.

Such a life position can be a model for today's Christians; the path of the new martyrs can be our path.

Intellectual heritage of the new martyrs

Finally, something must be said about the intellectual heritage of the new martyrs. The main source here is church samizdat, which has been extremely little studied. Let us note its diversity: the thematic range of church samizdat varies from ascetic collections to apologetic works and works on pastoral psychology. It is not possible to talk about all these works, so I will dwell on only one such monument[10].

A prominent place among the heritage of church samizdat of the Soviet era is occupied by the book of Fr. Gleb Kaleda’s “Home Church,” which appeared as a complete text in the 1970s. “Home Church” is essentially the first book on family asceticism, that is, on spiritual life in marriage in the Russian Orthodox tradition. Traditionally, Orthodox ascetic writing was of a monastic nature, since the vast majority of authors followed the monastic path and were primarily interested in the laws and rules of the spiritual life of the monastic ascetic. And although many observations and recommendations of classical ascetic authors are universal in nature and relate to the spiritual life of any Christian - both monk and layman - at the same time, important specific issues of spiritual life in marriage either completely fell out of sight of ascetic writers, or were covered insufficiently, casually, sometimes exclusively from monastic positions.

In the book “The Home Church,” its author examined, from the point of view of their spiritual growth, a variety of aspects of the family life of Orthodox Christians. Moreover, this book was neither a collection of quotes from the Holy Fathers or spiritual writers, nor a scientific and theological work with a rationally constructed system of argumentation. It was an expression of the deep experience of the author - the head of the family, teacher, priest, experience, of course, personal, but rooted in Church Tradition, verified by him. In this sense, “Home Church” is in line with Orthodox ascetic writing, the best examples of which are an expression of the spiritual experience of their creators, the experience of meeting God and life in the Church. We can say that Father Gleb’s book is an expression of the experience of meeting God in a home church - in a family.

I would like to note one important feature of this work. Its author attaches exceptional importance to home Christian upbringing and education, the transfer from parents to children of their values and knowledge of their faith, which he calls nothing less than a home apostle. As the author writes, everyone who has a family and children is called to such apostolic service for their loved ones. At the same time, he carefully developed issues related to home education: its principles, stages, content, methods, the problem of combining it with general education.

All this absorbed the experience of the author himself, who already in the 1960s. While still a layman, he conducted Christian educational classes with children at his home, the participants of which were his children and the children of his relatives. But besides this - the experience of many home circles - children's, youth and adults - pre- and post-war times. In fact, these recommendations summarized the experience of the new martyrs in the field of Christian education. This experience was characterized by an exceptionally caring attitude towards the everyday life that surrounded the believer, towards the family and its organic - in spite of everything - development. And the high assessment of home Christian education as a home apostolate shows that the older contemporaries of the author of the “Home Church” and he himself understood the family as a field on which the modest everyday efforts of believing parents could defeat the full power of the soulless state machine.

conclusions

The experience of the new martyrs testifies to life in Christ. It was perceived as the main, enduring value, for the sake of which it was worth sacrificing a lot. She created new forms of church associations that realized themselves in Christian mutual assistance and in the extension of this assistance beyond the boundaries of communities. Despite everything, it entered into contemporary culture, testifying to the universality of Christianity. She was the treasure that only needed to be passed on to her children through the “home apostolate.” It seems that such an axiology of the generation of Russian martyrs and confessors is their main testament to us, requiring our full attention and comprehension[11].

[1] Exceptions to this rule include several examples of executions of clergy during the Civil War and the 1930s campaign to force clergy to publicly declare defrocking in exchange for restoration of civil rights and employment. In both cases we are talking about exceptions to the general rule. Moreover, although it is now difficult to assess the scale of the renunciations of the 30s, it is known that very often the renunciations did not achieve their goal, because former priests continued to be discriminated against because they were “historically” classified as an unreliable category of citizens. This issue was even considered by the All-Russian Central Executive Committee commission on religious affairs. See, for example, the Draft Circular of the Presidium of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee on distortions and violations of the legislation on cults. June 10, 1932 // Russian Orthodox Church and the communist state. 1917–1941. Documents and photographic materials. M., 1996. pp. 294–295.

[2] Shmaina-Velikanova A.I. About new martyrs // Pages: Theology. Culture. Education. 1998. T. 3. Issue. 4. pp. 504–509; Semenenko-Basin I.V. Holiness in Russian Orthodox culture of the twentieth century. History of personification. M., 2010. pp. 214–217.

[3] Alekseeva L. History of dissent in the USSR. New York, 1984; Vilnius, Moscow, 1992. Shkarovsky M.V. Josephlanism: a movement in the Russian Orthodox Church. St. Petersburg, 1999, etc.

[4] Harbin residents are employees of the Chinese Eastern Railway (CER), built before the revolution on territory leased by Russia from China. The city of Harbin was the center of this territory. After the USSR sold the Chinese Eastern Railway to Japan in 1935, many “Harbin residents” returned to their homeland, where they were assigned a place of residence in Siberia.

[5] See, for example, Beglov A., Chakovskaya L. Ordinary heroism // Tatyana’s Day. Edition of the home church of St. mts. Tatiana at Moscow State University. M.V. Lomonosov. October 1, 2010: https://www.taday.ru/text/651147.html.

[6] Antonov V.V. Parish Orthodox brotherhoods in Petrograd (1920s) // The Past: Historical Almanac. Vol. 15. M.–SPb., 1993. pp. 424–445; Antonov V.V. Alexander Nevsky Brotherhood and secret monastic communities in Petrograd // St. Petersburg Diocesan Gazette. 2000. Vol. 23. pp. 103–112; Shkarovsky M.V. Alexander Nevsky Brotherhood. 1918–1932. St. Petersburg, 2003; Beglov A.L. Church and social movements at the turn of the 1910s–1920s // XIX Annual Theological Conference of the Orthodox St. Tikhon's Humanitarian University: Materials. T. 1; Zegzhda S.A. Alexander Nevsky Brotherhood. St. Petersburg, 2009.

[7] This suggests a direct parallel with the early Christian communities, which by the end of the 3rd century. took on the broadest social functions in the ancient polis - they buried the dead during epidemics, took care of widows (and not only those belonging to the Christian community), fed orphans, etc. Wed. Brown P. The World of Late Antiquity. Thames and Hudson, 1971.

[8] Fitzpatrick S. Stalin’s peasants. Social history of Soviet Russia in the 30s: village. M., 2008. pp. 231–233.

[9] Beglov A.L. Church underground in the USSR in the 1920–1940s: strategies for survival // Odyssey. Man in history. 2003. M., 2003. S. 78–104; Beglov A.L. In search of “sinless catacombs”. Church underground in the USSR. M., 2008. P. 78–85; Beglov A. Il monachesimo clandestino in URSS e il suo rapporto con la cultura secolare // La nuova Europa. Rivista internationale di cultura. 2010, Gennaio. No. 1. Pp. 136–145.

[10] Beglov A.L. Home education as an apostolic ministry. The concept of church education of Archpriest Gleb Kaleda // Journal of the Moscow Patriarchate. 2009. No. 11. P. 77–83; Beglov A.L. Orthodox education underground: traditions and innovations. The experience of priest Gleb Kaleda // Menevskie readings. 2007. Scientific conference “Orthodox pedagogy”. Sergiev Posad, 2008. pp. 90–100; Beglov A.L. Orthodox education in the underground: pages of history // Alpha and Omega. 2007. No. 3(50). pp. 153–172.

[11] Another possible conclusion from our proposed understanding of the feat of the new martyrs as a continuation of life in Christ concerns the specific practice of glorification in this rank of saints.

It seems that when preparing materials for the canonization of the new martyrs, attention should be transferred from “documents about death,” that is, investigative files that today underlie the canonization process, to “documents about the lives” of these people, first of all, to church tradition and other evidence about their position in life. www.bogoslov.ru