Tsar Peter I influenced the history of the Russian Orthodox Church. It was with Peter's reform that the so-called Synodal period began in the development of the church, which lasted more than two centuries.

Some historians, for example, Archpriest Vladislav Tsypin, consider the beginning of the synodal period to be 1700, when, after the death of Patriarch Adrian, Peter violated the previously established order and did not convene the Local Council to choose a new patriarch, but appointed the guardian of the patriarchal throne - Metropolitan Stefan Yavorsky.

The second part of the researchers identifies the beginning of the Synodal period in 1721 - the abolition of the patriarchate and the creation of the Spiritual College, which was later called the Holy Governing Synod.

At the end of the period there are no disputes or discrepancies - 1917, the proclamation of the power of the Soviets and the persecution of faith and the church.

Buildings of the Senate and Synod in St. Petersburg. Members of the Holy Synod made decisions here, instead of the usual Local Councils

What is the Synodal period?

This is what historians call the era from February 1721 to November 1917—almost 200 years. All this time, the highest authority of the Russian Orthodox Church was the Holy Synod, established by Peter I. It was a meeting of the most influential hierarchs of the Russian Church, heading the largest Russian departments - St. Petersburg, Moscow, Kazan, Kyiv. At first, the Synod included not only bishops, but also abbots of large monasteries, and representatives of the white clergy (that is, married priests), and even secular officials.

Peter I establishes the Holy Synod. Painting by Ivan Tupylev. 1801

Under Peter, the Synod was conceived as a church government. He dealt with matters of a spiritual order, was called the Governing One and had the emperor himself as the “ultimate judge” (like the Senate, also created by Peter and responsible for civil affairs). Later it turned into a kind of ministry. Ministries as such were created only at the beginning of the 19th century under Alexander I for Church affairs. In official documents of the 19th century, the Synod was called the “department of the Orthodox confession,” by analogy with the departments of military, financial, internal affairs, etc.

But, no matter what status the Synod had in different years, the essence remained the same: all this time, church power remained firmly integrated into the system of government. This corresponded to Peter’s worldview: he was a sincere and religious person, but he believed that the Church was called upon first of all to serve the state and society.

Sources of church law of the synodal era.

In 1776, on behalf of the Holy Synod, the “Book on the Positions of Parish Elders,” compiled somewhat earlier by Bishops George (Konissky) and Parthenius (Sopkovsky), was published. Subsequently, it was reprinted many times. This is a practical guide for pastors with extracts from the “Helmsman,” “Spiritual Regulations,” the most important synodal decrees, as well as from the writings of the Fathers. The book also contains such instructions that cannot be found in other authoritative sources of Russian church law. For example, permission to allow non-Orthodox people to be the baptismal parents of Orthodox children with the only condition that they read the Niceno-Tsaregrad symbol without filioque.

The Synod more than once ordered that this book be followed when imposing penances by confessors and church courts. Its study was included in the programs of theological schools until the middle of the 19th century; many generations of Russian priests used it to prepare themselves for pastoral parish service.

The Helmsman's Book was reprinted many times by the Holy Synod; in principle, it was recognized as the most authoritative collection of church law, since in the “Spiritual Regulations” the canons were recognized as having binding force. But in “The Helmsman” the rules were given in an abbreviated form (according to the “Synopsis”); their translation into Slavic is in many places inaccurate and difficult to understand. The disadvantage of “The Helmsman” as a practical guide to church law was also that some of the documents contained in it (and these were mainly legislative acts of the Byzantine emperors) were outdated and fell out of use.

Therefore, in 1839, instead of the “Helmsman’s Book,” the publication of the “Book of Rules” was undertaken, where, along with the Greek text, a parallel translation of the canons into Church Slavonic, close to the Russian language, was given. Later, when the “Book of Rules” was republished, only the translation was included (without the original text).

The main advantage of the “Book of Rules” was that, firstly, the canons were reproduced in full, and secondly, only the main canonical corpus was included in the “Book”. The rules were here separated from the heterogeneous legal material, either of lesser authority or completely lost force, with which “The Helmsman” is overloaded.

At the same time, the “Book of Rules” is not without textual shortcomings: the translation is not always satisfactory. Canonists also noted direct errors in the translation of individual Greek terms. Probably due to the translator’s vague understanding of the state-administrative division of the Roman Empire and the territorial division of the Ancient Church, the words “παροικια” and “επαρχια” are not always translated correctly.

In the rules, the first word “παροικια” in almost all cases designates a bishopric, in our opinion, a diocese, and the second word “επαρχια” means a metropolitan district. In the Book of Rules, the first word is often translated as “parish,” and the second as “diocese.”

In the synodal editions of the “Book of Rules” there are no interpretations of these rules. But at the end of the 19th century they were published in several editions by the “Society of Lovers of Spiritual Enlightenment” with the blessing of the Synod with interpretations of Aristin, Zonara and Balsamon and with a brief summary of the rules according to the “Helmsman’s Book.”

In 1841, the “Charter of Spiritual Consistories,” approved by the Synod, was first published, thoroughly revised in 1883. This is a kind of “Spiritual Regulation” of diocesan administration. It consists of 364 articles organized into four sections. The first section deals with the significance of consistories and the legal basis of diocesan administration and court, the second - with the responsibilities of consistories for the protection and dissemination of the Orthodox faith, for worship, for the construction and improvement of churches, and for church housekeeping. The third section is devoted to the diocesan court, and the fourth - to the states of the consistories themselves and the regulations of their office work.

The “Charter” was based on the “Spiritual Regulations” and individual previously issued decrees on diocesan administration, which were brought together in this collection.

Many of the decrees of the Synod and other legal acts of the Office of Orthodox Confession were not codified. They were scattered across various official periodicals: they were published in “Church Gazette,” “Church Bulletin,” “Spiritual Conversation.” Some of the legislative acts, although not codified in the strict sense, were systematized, being published in the form of separate books and brochures. These are the Statutes of religious educational institutions, Instructions for church elders, deans of parish churches and monasteries, and Rules on local means of maintaining the clergy.

Since 1879, the publication of the “Complete Collection of Decrees and Orders for the Department of the Orthodox Confession of the Russian Empire” began in St. Petersburg. The ten volumes of the “Collection” cover church legislation from Peter I to Elizabeth.

From 1868 to 1917 eleven volumes of another fundamental collection were published: “Description of documents and files stored in the archives of the Holy Synod.” As the title suggests, this publication does not publish the documents themselves, but only contains their descriptions.

Decrees on the Office of the Orthodox Confession are also placed in the “Complete Collection of Laws of the Russian Empire” in chronological order. In the codified collection - the “Code of Laws of the Russian Empire” - laws and decrees concerning the Church are placed in Volume I (the basic laws in which the emperor’s confession of Orthodoxy is proclaimed); “Charter on Civil Service,” which also talks about clergy in connection with general rules on awards, salaries and pensions - in Volume III; “The Charter on Duties,” individual articles of which relate to the clergy, their property and church property, are in Volume IV; “Forest Charter” - about forests owned by church institutions, and “Accounting Charter” - about control under the Holy Synod - in Volume VIII; Volume IX (“Laws on State”) sets out the laws on the class rights of the white and monastic clergy; Volume XIII (“Charter of Public Charity and Medical Charter”) contains laws relating to diocesan care for the poor of the clergy; Volume XIV (“Charter on detention and statute on the prevention and suppression of crimes”) includes laws on prison churches, crimes against faith and the Church; Volume XVI (“Charters of Legal Proceedings”) contains laws on legal proceedings in cases of crimes against the Church and in civil cases of church institutions.

In 1905, the political system of the Russian Empire underwent radical transformations. The highest legislative bodies, in addition to the emperor, were the State Council and the State Duma. Naturally, they included not only Orthodox individuals. However, laws concerning the Orthodox Church, such as those concerning the financial estimates of the Synod, were considered by the State Council and the Duma.

In the church environment, as well as in government spheres, the question of convening a Local Council was raised. Preparations for it continued intermittently until August 1917. Documents related to the preparation of the Council, although they never had mandatory significance, nevertheless represent important church-historical and, in a sense, church-legal monuments, since they reflect the canonical consciousness episcopate, clergy and laity. Particularly interesting are the “Reviews of diocesan bishops on the issue of church reform,” published in 1906, and “Journals and minutes of meetings of the Pre-Conciliar Presence,” published in the “Church Gazette” in 1906-1907, as well as in a separate publication in 1906-1909 gg.

What about the Patriarch? Isn't he the head of the Church?

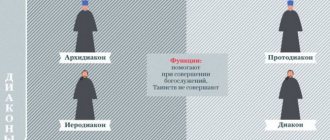

During this period, the Russian Church simply did not have a patriarch. It was he who was replaced by the Synod. But before we talk about this, let's figure out who has what power in the Church.

The head of the Church has always been and remains the Lord Jesus Christ Himself , Who created it about 2000 years ago from the community of His closest disciples - the twelve apostles. All power in the Church belongs to Christ. For Christians, there is no doubt that the One who said to the apostles: Behold, I am with you always, even to the end of the age (Matthew 28:20 ), and today is really present with us, governing all aspects of the life of His Church, which the Apostle Paul called the body of Christ, composed of many members - individual believers (cf. 1 Cor 12 : 12-14).

But Christ wants this power to be exercised through people in the daily life of the Church. After all, the Church is not a purely spiritual community of people united with Christ by faith alone. This is also an earthly community structured in a certain way, in which the spiritual unity of Christians is realized practically (through prayer, sacraments, works of mercy, etc.).

This ecclesiastical authority, delegated by Christ to the people, was conciliar from the very beginning . Both the dogmas of faith and the specific rules of church life have always been approved not by some hierarch, even the most authoritative one, but by a council of bishops. This is how Christ’s commandment about the unity of believers was fulfilled: That they may all be one, just as You, Father, are in Me, and I in You, that they also may be one in Us, so that the world may believe that You sent Me (John 17:21 ) . It was in the conciliar unity of bishops - representatives of individual church communities, together forming the fullness of the Church - that the Holy Spirit revealed Himself.

Church judgment was also carried out at councils - for example, over heretics.

But issues of daily management of church communities have always been dealt with by bishops - the heirs of the apostles . After all, decisions need to be made every day, and you cannot hold a Council every time. At the same time, since apostolic times, there has been a rule: “it is fitting for the bishops of every nation to know the first in them, and recognize him as the head, and not do anything that exceeds their authority without his reasoning.” The Patriarch became such a bishop - the first among equals. In the ancient local Churches, the title of Patriarch appeared from the end of the 4th - 5th centuries. In the Russian Church, the Patriarch was first elected by the Council of Bishops in 1589.

Trial of heretics

The patriarchs resolved issues related to the management of Local Churches as a whole, expressed the views of Christians to the outside world, and built cooperation between the Church and secular authorities. An important part of the Patriarch's ministry was to oversee the regular convening of Councils, which were supposed to approve all key decisions affecting the life of the Local Church. This is how it works to this day. In the Russian Orthodox Church, all the most important decisions made by the Holy Synod under the chairmanship of the Patriarch are then approved by the Council of Bishops.

The Patriarch has never been the head of the Local Church in the literal sense of the word. He was her face and enjoyed the “primacy of honor” among her bishops. In Russia, the Patriarch, in addition to this, is also the ruling bishop of the capital diocese - the city of Moscow.

Sources of church law of the newest era.

Local Council of the Russian Orthodox Church 1917-1918. and the restoration of the Patriarchate opened a new period in the history of our Church. Local Councils re-entered the life of the Church as its highest canonical body. The cathedral continued its work for more than a year. All important issues of church life were discussed at it: about the structure of the highest church authority and diocesan administration, about the relationship between the Church and the state, about preaching, about theological schools, monasteries. Due to the circumstances of that time, the program of the Council was not fully implemented.

Nevertheless, the Council issued a number of definitions, which were published in the church press and were published in 1918 as a separate publication in 4 issues entitled “Definitions.” The most important of these definitions are the following: “On the rights and duties of His Holiness the Patriarch of Moscow and All Russia,” “On the Holy Synod and the Supreme Church Council,” “On the range of affairs subject to the jurisdiction of the bodies of the highest church government,” “On the procedure for electing His Holiness the Patriarch,” “ About the Locum Tenens of the Patriarchal Throne,” “On diocesan administration,” “On vicar bishops,” “On the Orthodox parish” (Parish Charter), “On monasteries and monastics,” “On reasons for divorce,” “On the legal status of the Church in the state ,” “On attracting women to active participation in various fields of church service.”

These definitions constituted the real code of the Russian Orthodox Church, which replaced the “Spiritual Regulations,” the “Charter of Spiritual Consistories” and a whole series of more specific legislative acts of the synodal era.

In resolving issues of all church life on the basis of strict fidelity to Orthodox dogma, on the basis of canonical truth, the Local Council revealed the uncloudedness of the conciliar mind of the Church. The canonical definitions of the Council served for the Russian Church on its arduous path as a firm support and an unmistakable spiritual guide in solving extremely difficult problems that life subsequently presented to it in abundance.

In 1945, a new Local Council was held, at which Metropolitan Alexy (Simansky) of Leningrad was elected Patriarch. The Council issued a brief “Regulations on the Russian Orthodox Church,” which replaced the “Definitions” of the Council of 1917-1918. There is an undoubted continuity between the legislative acts of the two Local Councils, but the changes made, due to the circumstances of the time, based on the invaluable experience experienced by the Church, consisted, in general, in emphasizing the hierarchy of the church system. The “regulations” of the 1945 Council expanded the competence of the Patriarch, diocesan bishop, and parish rector.

The Council of Bishops, held in 1961, revised the “Regulations on the Russian Orthodox Church” in terms of parish administration; clergy were removed from the management of the material resources of the parishes, which was now entrusted exclusively to parish meetings and parish councils, headed by their chairmen-elders.

The Local Council of 1971, at which Metropolitan Pimen (Izvekov) of Krutitsa and Kolomna was elected Patriarch of Moscow and All Rus', approved the changes made to the “Regulations on the Russian Orthodox Church” by the Council of Bishops in 1961. The Local Council also issued a resolution on the abolition of the Greater oaths Moscow Council of 1667 on old rites.

The Local Council, held in 1988 - in the year of the millennium of the Baptism of Rus', - issued the "Charter of the Russian Orthodox Church" - the main current law of our local Church, which regulates the structure of the highest , diocesan and parish administration, activities of theological schools and monasteries. The “Charter” incorporated the principles of the church system that have stood the test of life, which formed the basis of the “Definitions” of the Local Council of 1917-1918. and the “Regulations,” issued by the Council in 1945.

The Journal of the Moscow Patriarchate regularly publishes definitions of the Holy Synod and decrees of His Holiness the Patriarch, including those that are normative in nature.

The external law of our Church is determined by state laws and regulations, which are published in official periodicals and separate collections. Particularly complete in the selection of legal acts relating to religious associations, in particular the Russian Orthodox Church, is the collection of Professor P. V. Gidulyanov “Separation of the Church from the State,” published in the third and last edition in 1926. This collection, naturally, includes legal acts relating to the first decade of the history of the Soviet state.

Why was there no Patriarch during the Synodal period?

The position of Patriarch was abolished by the “Spiritual Regulations” - a special legislative act drawn up in 1720 at the direction of Peter I by his closest associate in church affairs, Archbishop Feofan (Prokopovich). The “Spiritual Regulations” declared the patriarchal management system to be ineffective, bureaucratic, potentially competing with royal power and even gravitating towards papism. And the Synod is a collegial body, it will come to the truth sooner than an individual hierarch-autocrat, wrote Feofan (Prokopovich).

Many of these arguments were obvious stretches. The Orthodox Patriarch, unlike the Pope, was never perceived as the bearer of absolute power in the Church, and all his decisions were approved by the Councils. What motives really motivated Peter?

Of course, his interest in the way of life in the countries of Western Europe, where Protestantism and the ethics of the public good had dominated for two centuries, played a significant role. But first of all, Peter was guided by considerations of imperial logic: in the empire, absolutely everything serves the interests of the state, and there simply cannot be any other center of public life.

Peter wanted to put an end to the dispute started by his father, Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich, and Patriarch Nikon: what is higher - the kingdom or the priesthood? This dispute became the cause of a protracted conflict between the sovereign and the Patriarch. Moreover, for Nikon the matter ended in deposition and exile, and for the entire Church - in a very difficult (and still not overcome) schism on the basis of “Nikonian” liturgical reforms.

The Russian Church emerged from this schism in a greatly weakened state. Russian hierarchs, taught by the bitter experience of Patriarch Nikon and Archpriest Avvakum, tried not to show unnecessary initiative. The situation was aggravated, as a rule, by the low level of education of the Russian clergy: it met less and less the expectations of Peter, who was carried away by the ideas of progress and enlightenment during his European trips.

Patriarch Adrian

Peter’s personal experience of relationships with church authorities was also not the most successful. The Tsar did not get along well with Patriarch Adrian, who headed the Russian Church in the last decade of the 17th century. Peter was especially angry when he began to petition him for pardon for the Streltsy, who had committed a riot in Moscow while Peter was traveling around Europe. When Adrian died, Peter did not convene a Council to elect a successor. For twenty years the Russian Church was ruled not by the Patriarch, but by the Locum Tenens of the Patriarchal Throne, Metropolitan Stefan (Yavorsky) of Ryazan and Murom, and the tsar’s relationship with him was also tense. All this strengthened Peter in his idea to completely abolish the Patriarchate. This is what was done in February 1721, with the establishment of the Synod. Even the title “Holiness,” formerly held by the Patriarch, passed to him. The patriarchy is a thing of the past.

And what did this change for the Church in essence?

The absence of the Patriarch, of course, did not call into question the very existence of the Church in Russia. The conciliar form of government of the Church was preserved, and the Eastern Patriarchs readily agreed to consider the Russian Synod their “brother in Christ.”

Another thing is that the figure authorized to conduct a dialogue with state authorities on behalf of the Church, express the views of the Church, and inspire Christians to live according to the Gospel has disappeared. The Russian Church has literally lost face.

All this led to the fact that the Russian Church was integrated into the state administrative apparatus.

On paper, everything looked smooth: the Church, as before, was governed by a council of bishops, because the Holy Synod was truly a collegial body. But they stopped convening real Local Councils. And the decisions of the Synod, like all church life in Russia, began to be increasingly determined by the will of secular officials and, ultimately, the emperor or empress. The composition of the Synod was approved by the emperor personally; all synodal resolutions up to 1917 were issued with the stamp “By order of His Imperial Majesty.” This could be explained by continuity in relation to Byzantium (in its church hierarchy, the emperor, as the anointed of God, really occupied a special place, was perceived as the “bishop of external affairs,” an intercessor before God for all the laity), if not for the much closer example of Protestant countries, the rulers who did not hesitate to declare themselves the heads of the local churches. But Peter took his example from them.

During the Synodal era, the Church was subordinated to the state. In their relationship, once harmonious, there was a sharp imbalance. This was a natural result of violating the rule of the holy apostles about the “first bishop.”

What exactly did the state put pressure on the Church?

The Synodal period lasted almost two centuries, and at different times, state intervention in church affairs led to different consequences.

On the one hand, sometimes the emperor’s personal participation even helped. This happened, for example, in 1903, when Nicholas II gave up on the endless disagreements among the members of the Synod and ordered the canonization of St. Seraphim of Sarov.

Nicholas II and the Grand Dukes carry the coffin with the relics of St. Seraphim of Sarov to a new burial place. July 18, 1903

On the other hand, by the voluntaristic decision of the tsar, completely odious figures could penetrate into the Synod (as, for example, during the reign of Anna Ioannovna - 1730–1740), and worthy archpastors, such as Metropolitan Philaret (Drozdov) of Moscow, could, on the contrary, be removed from the Synod. exclude ill-wishers from entering the palace based on slander.

Already in the 19th century, the figure of the chief prosecutor - a secular official with the rank of minister - acquired enormous weight. According to his job description, he was supposed to only oversee the work of the Synod as an observer, but in reality he often used, as we would say today, administrative resources and imposed his personal decisions and views on the Church. Among the chief prosecutors there were people worthy and devoted to the Church. Such were, with all the ambiguity of their views, Alexander Nikolaevich Golitsyn (1803–1816), a friend of his youth and associate of Alexander I, and later Konstantin Petrovich Pobedonostsev (1880–1905). But there were also rude, arrogant and even non-church people, such as Count Dmitry Andreevich Tolstoy (1865–1880), the author of one of the most unsuccessful reforms of religious education in Russia.

Konstantin Petrovich Pobedonostsev

During the Synodal era, the Russian Church was under unprecedented control and pressure from the state. And this is the main feature of this period.

Three hundred years ago the Russian Church was subordinated to the state

The single complex of buildings of the Senate and Synod symbolized the harmony of civil and ecclesiastical principles in the imperial hierarchy. Karl Beggrov. View of the Senate and Synod buildings. 1830s Hermitage

Emperor Peter the Great opened a new page in the history of the Russian Orthodox Church. On January 25 (February 5, new style), 1721, the “Regulations or Charter of the Spiritual College” was approved, and on February 14 this very college began to work, which received the name of the Holy Governing Synod.

They often talk about the unfreedom of the church in those two centuries when it was not led by patriarchs. But there is no need to exaggerate the severity of lack of freedom, in particular the dictates of the bureaucracy. Being incorporated into the state apparatus as an organization, the church remained independent as a mystical association of believers.

Moreover, state confession had privileges. Throughout the Synodal era, the authorities performed a protective function. Pashkovites, Doukhobors, Old Believers - all opponents of the official church experienced the weight of the imperial hand. The Church willingly resorted to the help of the state to suppress dissidents and other believers.

Synodal orders made it possible to develop spiritual education and missionary work. In the 19th – early 20th centuries, the monasteries became stronger financially. The church influenced secular culture. We can talk about relative financial transparency: the relevant reports of church structures were published in the press. There was a certain freedom of expression. The priest John Bellustin, while actively criticizing the church system in the press, was never banned from serving; there was no talk of defrocking at all. The spiritual consistories and their secretaries were a counterweight to bishop's despotism. The Synod has more than once defended ordinary clergy from oppression by hierarchs.

And yet, Peter’s reform was received ambiguously in church circles. There were both defenders of the synodal order and ardent opponents.

Sovereign Church

An official under the Chief Prosecutor, Vasily Skvortsov, wrote: “There have always been... among diocesan bishops those who prefer the synodal system of governing the patriarchate.” Defenders of the synodal order called not to exaggerate the lack of freedom of the clergy. Fellow Chief Prosecutor Nikolai Zhevakhov explained: “The hierarchs of the Church, not excluding the most sincere opponents of the synodal system, of course, knew very well that references to shackles and slavery, in which the Church was for 200 years... all these are just current phrases invented by ambitious people.”

Among those who accepted the synodal system was Bishop Ignatius (Brianchaninov). Some of his words about the Synod sound almost tender. In one of the hierarch’s letters (1852) we find: “The members of the Holy Synod are all very kind elders, and Count Protasov (Chief Prosecutor - NGR) has the kindest heart.” While other hierarchs shuddered at the mere mention of Protasov’s name.

Pragmatically minded bishops, for example, Metropolitan Filaret (Drozdov), agreeing with the synodal system, only wanted greater self-government for the church. Drozdov developed the doctrine of the divine nature of the Russian autocracy. He preached the supremacy of royal power and the importance of submission to it. In the 20th century, church officialdom assessed the views of its predecessors as “fanatical devotion of a part of the pre-revolutionary Orthodox clergy... to the idea of Russian statehood, expressed by the formula “Orthodoxy and autocracy” (Journal of the Moscow Patriarchate. 1968, No. 5).

According to Vasily Rozanov, Filaret “honored the Synod, there was a conscious synod” (“Apocalypse of Our Time”). Here is what Archbishop Leonid (Krasnopevkov) said about Drozdov in 1860: “Vladyka developed the idea that with prudence one can live among the circumstances that surround bishops. Through the predominance of secular power, everything essential can be defended, as long as one does not irritate with trifles, untimely and harsh actions” (From the notes of the Right Reverend Leonid. M., 1907).

Perhaps the highest assessment of the Synod was given by Bishop Arseny (Zhadanovsky): “The Holy Synod constitutes the soul of our... Church... The Synod is an institution given to us by the Providence of God... It is impossible to call... the Synod an institution without grace... The Holy Church, even in the Synodal era, is filled with grace and power!.. A faithful son of the Church would probably be touched and bowed down before the activities of the Holy Synod.”

Protopresbyter Alexander Schmemann discussed the positive aspects of the system: “The Synodal period, contrary to a very widespread belief, cannot in any way be considered a time of decline, impoverishment of spiritual strength, or some kind of degeneration.” “The Orthodox consciousness “did not notice” ... Peter’s reform,” Schmemann also said. In a 1980 publication of the Moscow Patriarchate, Peter’s reform was called “a beneficial suffering for the Russian Church, which stimulated its creative powers.” Even its opponents spoke about the positive aspects of the system, for example, Patriarch Alexy II (Ridiger): Orthodoxy under the Synod “revealed the greatest spiritual achievements in those areas where the state bureaucracy was not omnipotent.” Among the modern clergy there are also adherents of the synodal system, for example Archpriest Valentin Asmus.

Church enslaved

Bishop Nikodim (Kazantsev), a bishop of the 19th century, believed: the appointment of the chief prosecutor “at one time enslaved the Synod to the tsar’s politics, deprived it of freedom of consultation and freedom to decide church affairs... the fathers of the Synod, enslaved to the prosecutor, are forced to servile to the dreams of the prosecutor” (On His Holiness Synod. Sergiev Posad, 1905).

Sometimes things got funny. One day, while waiting for Chief Prosecutor Nikolai Protasov, members of the presence “began... heatedly discussing the election of a rector for Solovki. Voitsekhovich (synodal official - “NGR”) could not resist, came up and interrupted their meeting with the words: “Count Nikolai Alexandrovich has already elected.” Everything fell silent... The arriving count confirmed the news” (From the notes of His Eminence Leonid. M., 1907).

| With the creation of the synodal system of governance, Peter I gave rise to a special era in the history of the Russian Orthodox Church. Ivan Tupylev. Peter the Great and the Holy Synod. 1801 |

In 1723, the legitimacy of the Synod was recognized by the Eastern patriarchs, which not everyone liked.

Kazantsev argued: “The approval of the charter ... of the Synod by the Eastern Patriarchs carries within itself signs of destruction.” Most of the hierarchs nevertheless came to terms with the synodal order. The demarche of Metropolitan Arseny (Matseevich), who declared anathema to Catherine II, is an exception to the rule. Matseevich’s note “On Church Deanery” became the first major speech against the synodal system. The leading member of the Synod, Archbishop Ambrose (Yushkevich), also put his name under the “Note.” Matseevich was an ardent adherent of spiritual authority and its right to independent government and judiciary.

There were other cases of open resistance to the synodal orders. In 1813, the Georgian Metropolitan Arseny refused to carry out the order of the Synod. “There is no other way to force him... than if they order him to be put on guard by force,” he said about himself in the third person.

Church luminaries also took part in the discussion on this topic. Archbishop Innokenty (Borisov) stated (after 1840): “Of all the institutions of the Russian Empire, there is not a single one that, in its inadequacy and disorder, could equal the present situation ... of the Synod. Regret and horror are overwhelming when you realize what he should be, what he is intended for... and what he really is, if his unfortunate situation threatens the Fatherland and the Church... Put anyone in it, even a policeman, no one will say a word" ( OR RNL, f. 313. Item 15. L. 3, 3 vol.).

Archbishop Filaret (Amphitheaters) allowed himself a more harsh description: “The reformers of the Church... are impostors and deceivers...” (OR RNL. F. 313. Item 40. L. 80). Nikodim (Kazantsev) wrote: “The members of the Synod have lost almost all their authority... With sadness I must say that the fathers of the Synod... cowardly tolerate the dominance of worldly power over themselves... the members of the Synod are like birds without wings.”

In the second half of the 19th century, when the social movement became more active, Metropolitan Arseny (Moskvin) criticized the synodal system. In turn, Metropolitan Grigory (Postnikov) in 1860, in a letter to Filaret (Drozdov), wished, in particular, to “destroy what was done by the late chief prosecutor” (Nikolai Protasov). Bishop Agafangel (Soloviev), a supporter of unlimited episcopal power over the parish clergy and a tough hierarch, did not hide his rejection of the synodal system. He is the author of the essay “The Captivity of the Russian Church.”

Protest sentiments grew, but most hierarchs waited, dreaming of a return to the pre-Petrine system. Bishop Porfiry (Uspensky) considered it necessary to “wait patiently... in the hope of a change in circumstances... for state legislation.” “What is our Synod? - asked Porfiry. “This is a beggar who is given grains from the chief prosecutor’s table, and not all of them.”

Metropolitan Palladius (Raev) also complained: “We (members of the synodal presence - NGR) cannot interrogate them (the synodal officials - NGR) so that we can be given a list of cases that are reported to us even on the eve of the meeting; they want us to decide impromptu. But for other matters a certificate is required.”

Members of the synodal presence, including the leader, were usually constrained in their actions. Arseny (Stadnitsky) noted in 1897 that even the Metropolitan of Moscow “is not ... able to do anything.” Stadnitsky had no doubt that the existing system of relations between church and state “is long overdue... it’s time to screw it up.”

“They think that those sitting in the Synod are partly equal to the patriarch,” said Bishop Anthony (Khrapovitsky), “and we are equal to half of any secretary and no more ... a fifth of the director of the office (Synod. - “NGR”)” (RGIA. F. 796. Op. 205. D. 697. L. 99 vol.). Khrapovitsky was categorical: “The Summer Synod is half deaf and half headless” (Ibid. L. 109 vol.).

At the beginning of the 20th century, in order to quickly liberate the church from the “synodal shackles,” 32 St. Petersburg priests compiled an appeal “On the need for changes in Russian church administration.” The first Russian revolution further activated the clergy and updated church issues.

Bishop Evdokim (Meshchersky) wondered: “Isn’t it timely to eliminate or at least somewhat weaken that constant guardianship and that too vigilant control of secular power over church life, which deprives the Church of independence... and, limiting the power of its conduct almost exclusively to worship and the correction of requirements, makes her voice completely inaudible?

Arseny (Stadnitsky) admitted: “The abundance of secular officials (in the Synod - NGR) ... amazed me.” Another time he was already indignant: “Are the metropolitans really dependent on the Vladimir Karlovichs (chief prosecutors - NGR)?.. And the Vladimir Karlovichs... secretly do whatever they want in the Church.” He said: “It pains me very much that we, the spiritual ones, are not being disposed of by those who should.”

According to Eulogius (Georgievsky), “the humiliation of the Church, the subordination of its state power was felt very strongly in the Synod... The Synod had no face, could not cast a voice... The state principle drowned out everything... This long forced silence and subordination to the state created skills in the Synod itself... decide matters in the spirit of external, formal church authority.”

The leading member of the Synod, Metropolitan Anthony (Vadkovsky), was not silent either. In 1905, he addressed a “Note” to the monarch, outlining his vision of the problems of the church. In particular, he expressed the wish “that the voice of the Church be heard in government administration.”

In 1905, with the participation of churchmen, a Special Meeting was created to prepare a draft of church reforms. And it issued a new “Note”, which sharply criticized the synodal system and proposed decentralization of church government. It calls the Synod a “bureaucratic institution” that has “non-canonical features of conciliarity”; a new concept is proposed: “The Church needs an alliance with the state... so as not to weaken the independent activity of either the church or the state body.”

In response, the chief prosecutor of the Synod, Konstantin Pobedonostsev, tried to prove the canonicity of the synodal structure as a result of the original life of the Russian Church. Expecting the support of the diocesan bishops, he got them to speak out whether changes were needed.

The majority opinions were against the synodal system. Bishop Dimitri (Sperovsky) stated: “The only salvation of Russia... lies in granting... the Church freedom from the dominion of officials and bureaucrats.” In turn, the parish clergy, wary of the patriarchate and not wanting episcopal omnipotence, advocated the election of the episcopate. In the mentioned reviews, the hierarchs stood up for church freedom, meaning their own freedom by it.

According to Protopresbyter Georgy Shavelsky, “there was no owner in the Synod, there was no responsible person,” his role was “somehow reduced, half-hearted.” And the Synod often dealt with the “little things” of church life. Once he reminded me of the importance of maintaining silence in churches during worship. The hierarchs were even in charge of purchasing firewood. As a member of the synodal presence, Protopresbyter Vasily Bazhanov was indignant: “We can only talk about drunken sextons.” Such minor issues as divorce cases or discussions of parish boundaries were conducted not in the dioceses, but in the Synod. Here is what Bishop Tikhon (Bellavin) wrote about his work at the beginning of the 20th century: “There were no particularly important matters during this time in the Synod; marriage cases were heard (and more signed)” (RGIA. F. 796. Op. 205. D. 752. L. 99 vol.).

A pessimistic view still prevailed. “The state will never agree to leave the Church without its control,” Bellavin argued in 1905 (RGIA. F. 796. Op. 205. D. 752. L. 148–148 vol.). It is interesting that it was Tikhon who was destined to complete the synodal period. In 1918, he was elected All-Russian Patriarch by the Local Council.

What specific problems and difficulties did this create for the Church?

One of the striking examples is the story of the translation of the Bible into Russian . Work on a modern (by the standards of the 19th century) translation of the Bible began back in 1815 on the initiative of Alexander I and proceeded under the leadership of Prince Alexander Golitsyn and St. Philaret (Drozdov). But in 1825 Nicholas I ascended the throne, and a year later he stopped this work. This decision was suggested to the emperor by a group of “zealots” who were convinced that the Bible should be read only in Church Slavonic. As a result, the first edition of the Bible in Russian (we now call this translation the Synodal) was published only in 1876.

The habit of looking back to authority in everything, developed among the members of the Synod by the middle of the 19th century, became the reason for the very slow canonization of saints . Only under Nicholas II did the glorification of God’s saints begin to gain momentum: during his reign, more ascetics were canonized as saints than in the previous 200 years!

The imposition of unusual functions on the Church over the lives of parishioners . Peter I entrusted especially many functions to priests. The most blatant requirement was to inform on people who came to confession and confessed to certain seditious acts, thoughts, or even such “crimes” as divulging false rumors about miracles, visions or prophecies ( Peter fought very energetically against superstitions, often considering innocent folk traditions as such). Later, the secret of confession was restored, but the state charged the priests with a lot of other duties: registering marriages, monitoring the regularity of communion for people who were listed as parishioners of their churches... All this, of course, did not increase trust in the Church.

By the way, it was during the Synodal period that the notorious tradition of taking communion once a year arose. It was born from the same attempt by the authorities to regulate the spiritual life of their citizens. Back in 1716, Peter issued a decree on compulsory annual communion for all Orthodox Christians. And until the beginning of the 20th century, civil servants were required to annually provide at their place of service a certificate of completion of the sacraments of Confession and Communion. All these requirements were introduced with a good purpose - to motivate Christians to take communion at least once a year. But the people quickly reinterpreted this as a norm prescribed by the state. They came to church once a year (most often during Lent), confessed, took the Chalice, took the coveted certificate from the priest - and disappeared until the next year, continuing to be considered Orthodox Christians.

But the flourishing of the Church is also associated with the Synodal period?

This is the paradox: this era, so controversial, became a time of unprecedented growth for the Church. True, the rise began already in the 19th century under such emperors as Alexander I and Nicholas I.

It was during this period that a coherent system of theological education arose in Russia: theological schools, seminaries and academies were established. A network of parochial schools developed throughout the country, in which almost half of the peasant children studied by the beginning of the 20th century. Theological science flourished, associated with the names of Metropolitans Platon (Levshin) and Philaret (Drozdov), Archbishop Philaret (Chernigov) and Metropolitan Macarius (Bulgakov), many outstanding professors of the Moscow, St. Petersburg, Kiev Theological Academies, as well as such laymen as Alexey Khomyakov and Ivan Kireevsky. Brilliant spiritual writers appeared - Saints Ignatius (Brianchaninov) and Theophan the Recluse, daring ascetic shepherds - John of Kronstadt, Alexy Mechev, Joseph Fudel.

A group of students from the Moscow Theological Seminary with Fr. Rector Archimandrite Sergius

Monasticism and monasteries flourished. The best spiritual traditions associated with the names of Saints Paisius Velichkovsky, Seraphim of Sarov, Ambrose of Optina, and Father Valentin Amfitheatrov were revived.

Russian missionaries reached the Far East, Korea and Japan, reached the shores of the Arctic Ocean, founded Christian communities in the Aleutian Islands, Central Asia, and established the Russian Spiritual Mission in Palestine...

19th century - rulers understood the importance of the Church as the spiritual support of the state

In the 19th century, the government of the Russian Empire changed its attitude towards the church and monasteries.

There comes an understanding of the need for solid spiritual supports of the state, and it is precisely this support that Emperor Alexander I sees in monasticism, his favorable attitude towards monasteries is continued by Nicholas I, Alexander III, but the string of pious emperors is crowned by Nicholas II, glorified as a saint.

Throughout the 19th century, monastic monasteries were created and restored.

Their financial situation is significantly improved thanks to donations from benefactors of various classes. Growing prosperity allows monasteries to build schools for peasants, open shelters and hospitals.

And all this happened thanks to the active participation of the state in the life of the Church?

No, not all. Although the Church really owed the revival of some traditions to the state. Without the support of the emperors and Chief Prosecutor Alexander Golitsyn, the formation of Russian religious education would have been impossible. Even at the beginning of the 19th century, nobles often looked down on the clergy, considering them a backward and poorly educated class. But already in the 1820s the situation began to change before our eyes. Thanks to the development of spiritual education, the smartest people paid attention to the Church, communication began between the intelligentsia and the clergy (let us just remember Pushkin’s correspondence with Metropolitan Philaret), and by the end of the 19th century, representatives of the aristocracy began to integrate into the ranks of the clergy (a typical example is Metropolitan Seraphim (Chichagov)) .

Metropolitan Seraphim (Chichagov)

With the advent of theological academies, the flowering of theological thought was not long in coming.

Many statesmen (including members of the royal family) and aristocrats actively participated in supporting missionary activities and charity. The example of Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich Romanov and his wife Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna, who were members of the boards of trustees of many dozens of charitable organizations and stood at the origins of the Imperial Palestine Society, is indicative.

Public education is also almost entirely the merit of the synodal system of power: Chief Prosecutor Konstantin Petrovich Pobedonostsev personally played a huge role in the development of parish schools.

But much in the life of the Church sprouted and sprouted not thanks to, but in spite of state policy. And above all, this concerns the revival of the living monastic tradition, clergy and eldership. During the reign of Catherine II (1762–1796), the monasteries fell into decay: having taken away land estates from the monasteries, the empress deprived them of any economic basis for existence, and government salaries were allocated extremely irregularly and on a residual basis. The favorable attitude of the emperors returned to the monasteries only in the 19th century. And yet, already from the end of the 18th century, a revival of monasticism began; pilgrims came here in search of spiritual mentors. And such mentors appeared.

Probably the most balanced answer to the question about the significance of the Synodal period for the Russian Church was given by Metropolitan Philaret of Moscow, who said: “The spiritual college, which Peter took over from the Protestant... God’s providence and the church spirit turned into the Holy Synod.” It is not so important who exactly governs the Church - the Patriarch or the Synod; it is not so important what powers are vested in the chief prosecutor, St. Philaret believed. Only one thing is important: how state power relates to the Church.

"Spiritual regulations."

The most important church-legal monument of the era, on which the foundations of the synodal system of church governance are based, is the “Spiritual Regulations,” compiled by Bishop Feofan (Prokopovich) in 1719, signed by the Consecrated Council and approved by Peter I in December 1720, and printed for the first time later, after the establishment of the Synod. The exact name of the document is “Regulations or Charter of the Theological College,” although, as is known, the board provided for in the “Regulations” was renamed at its first meeting into the “Holy Synod.”

The Regulations consist of three parts. In the first part, entitled “What is a spiritual college and what are the important faults of such a government?” gives a general idea of the collegial form of government and explains its advantages in comparison with individual power. The main argument here is the danger of dual power in the state.

The second part, entitled “Affairs of Administration Subject to This,” describes the range of affairs subordinate to the newly established church government. It also speaks in general terms about the duties of bishops, priests, monks and laity.

In the third part, “The stewards themselves, the position and power,” the composition of the Spiritual College and the duties of its members are determined.

According to A. S. Pavlov, “in its form and partly in its content, the “Spiritual Regulations” are not only a purely legislative act, but at the same time a literary monument. It is filled, like the famous “Order” of Catherine II, with general theoretical considerations, ... contains various projects, for example, on the establishment of Academies in Russia, and often falls into the tone of satire. Such, for example, are passages about episcopal power and honor, about episcopal visits, that is, bishops touring their dioceses, about church preachers, about popular superstitions shared by the clergy.”

In 1722, as an addition to the “Spiritual Regulations”, an “Addition on the Rules of the Church Clergy and the Order of Monasticism” was compiled, which contains entire statutes on the parish clergy and monasticism.

In addition to the “Regulations”, in 1722 an Imperial order was also issued on the selection of “a good man from among the officers” to occupy the position of chief prosecutor. In the same year, “Instructions to the Chief Prosecutor” were added to this order.

To evaluate the “Regulations” from the point of view of the consequences of its introduction into Russian church life means to make a judgment about the Synodal era itself. During the synodal period, as the most important church legal document, it received almost exclusively apologetic assessment in the literature. With the fall of this system, the reasons for such an attitude towards him disappeared. All the negative features of the era itself, and therefore of the “Regulations,” which formed the foundation of the legal structure of the Church, are completely obvious.

What was the reason for the restoration of the Patriarchate in 1917?

Ideas about the revival of the Patriarchate have been in the air since the beginning of the 20th century, but even at the opening of the Local Council of the Russian Orthodox Church in August 1917, few of its participants seriously discussed this possibility. The idea of restoring the Patriarchate became relevant only in the fall, when it became obvious that the Provisional Government was no longer in control of the situation in the country. Russia began to plunge into chaos before our eyes, power was increasingly clearly concentrated in the hands of the most radical forces with aggressive atheistic views and a willingness to shed blood.

At the local council in 1917

In this critical situation for the entire country, the Church, which had already lost a significant part of its powers (for example, the Provisional Government banned teaching the Law of God in schools), could not continue to remain faceless, controlled only by the Synod, over which even the emperor now did not stand. The general mood of the participants in the Local Council was well expressed by Bishop Mitrofan (Krasnopolsky) of Astrakhan. “In all the dangerous moments of Russian life, when the helm of the church began to tilt, the thought of the Patriarch was resurrected with special force,” he said. “The time imperatively demands feat, boldness, and the people want to see a living personality at the head of the life of the Church, who would gather the living forces of the people.”

The argument turned out to be convincing, and on November 5 (18), 1917, members of the Local Council elected St. Tikhon (Bellavin), at that time Metropolitan of Moscow and Kolomna, to the Patriarchal Throne.