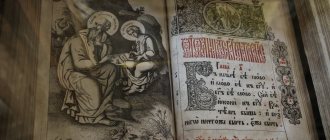

| St. Elena of Serbia, icon |

Helena of Serbia, Anjou

, monastic

Elizabeth

(+ 1314), Serbian queen, blessed saint Memory October 30

Born in the second quarter of the 13th century, the year and place of birth of St. Helena are unknown. She came from a noble French family, apparently living in Italy, the Byzantine possessions of the Crusaders or in Hungary and, perhaps, being in an unknown degree of kinship with the Angevin royal dynasty in Naples (its representatives, Kings Charles I and Charles II, referred to Helena in correspondence as " sister"), more specific information about her family is not available [1]. Nickname Anjou

in relation to Elena, it has been used in scientific literature since the late 1950s, starting with an article by G. Subotic.

She received a good education and spoke several languages. Between 1250 and 1255 was married to Stefan Urosh I in Serbia, gave birth to 5 children: Dragutin and Milutin, Stefan (grave in the Studenica monastery) and 2 daughters (one died in infancy, the fate of the other, Brnči (Prnči), unknown).

Throughout most of her life, she remained committed to the Roman Catholic Church and was a supporter of church union, to which she persuaded not only her husband and sons, but also her matchmaker (father-in-law Milutin), the Bulgarian Tsar George I Terter [2]. She was in correspondence with the Popes of Rome, and in 1303 she transferred her possessions to the tutelage of the Papal Throne [3]. She founded Franciscan monasteries near Bar and Kotor, gave (together with her sons) grants to the Benedictine monasteries of St. Mary on Cape Ratac (northwest of Bar), St. Nicholas and Saints Sergius and Bacchus on the river. Boyans (there are preserved Latin inscriptions with the names of Elena, Dragutin and Milutin) and Catholic. Cathedrals of Our Lady in Ulcinj and St. Stefan in Skadar (now Shkodra, Albania) [4].

Around 1291, she took part in the reorganization of bishops within the Bar Catholic diocese.

She placed Orthodox icons in the Cathedral of St. ap. Peter's in Rome and the Church of St. Nicholas, bishop Myra, in Bari (Italy).

She maintained close ties with the Catholic patriciate of cities in Dalmatia. In correspondence with one of the heads (“knez”) of the administration of Dubrovnik, she called the addressee Marin Buduari “beloved son and godfather of the kingdom,” and the bonds of “sisterhood according to St. John the Baptist" since 1285, she was associated with a representative of the Dubrovnik aristocratic family of Busignolo [5].

Together with her husband, she gave a letter of grant (later confirmed by Milutin) to the noble family of Zharetich, several. whose representatives were local Catholics. archbishops. Later, together with her son Milutin, she granted the nearby town of Grbalj to the city of Kotor. The ruler of her office and envoy to the papal court was a Catholic archdeacon. Peter Zharetich from Bar (Archbishop of Bar in 1301-1307) [6].

At the same time, the queen patronized the Orthodox Church and was on good terms with the primates of the Serbian Church, Archbishop. St. Ioannikiy I and especially with Daniel II (when the latter was a monk and bishop). According to the Life, she corresponded with hermits on Mount Athos, Sinai, Jerusalem and Raifa.

Having received power in 1276, Elena's eldest son, King Dragutin, allocated her a vast inheritance, which included Zeta, Trebinje, lands from Dubrovnik to Skadar (Elena's residence at that time was the city of Skadar).

After his death in 1279, Archbishop. Joannikia Elena participated in the transfer of his relics to the Sopočani monastery.

Around 1284 (?) she took monastic vows with the name Elizabeth in the church of St. Nicholas in Skadar.

In 1309, Elena's youngest son, King Milutin, took away his mother's inheritance in Primorye and in return gave land in the mainland. Elena's new courtyard was located in Brnjak, on the river. Ibar. According to the life, books were actively copied here, and a school-orphanage was created for girls from poor families and orphans, whom the queen provided with a rich dowry.

Saint Helena was the first woman in medieval Serbia to build herself a “zadushbina” - the Gradac Monastery. The Western masters she invited (probably from Provence) erected the monastery cathedral in a transitional style from Romanesque to Gothic, therefore the spread of the influence of French Gothic in Serbian church architecture (primarily in architectural decoration) is associated with the name of Elena. The monasteries she built and renovated were removed from the authority of the diocesan bishops; she appointed abbots to them, and after her death her descendants did this.

She died on February 8, 1314 in Brnjak (Kosovo). She was buried in the Gradack Monastery, the funeral service for her was performed by the archbishop. Savva III with the participation of Bishop. Daniel of Banski (later Archbishop of Pecs and biographer of St. Helena) and Pavel of Rash, cor. Milutin, Dragutin's envoys and numerous pupils of the orphanage she founded.

Reverence

According to the Life written by Archbishop. Daniel, three years after the death of St. Helena appeared in a dream to a certain monk of the Gradac monastery and ordered her body to be removed from the ground and opened for those coming to the temple. The abbot of the monastery notified in writing about the appearance of the bishop. Rashsky Paul, who arrived at the monastery and after the cathedral all-night singing and prayer, opened the tomb and discovered the body of the saint, “as if lying in the dew, whole (clean) uncorrupted” [7].

The relics, with the singing of prayers and psalms, were placed in a shrine and placed in front of the icon of the Savior (the current location of the shrine is unknown). Until the 18th century the relics were in a tomb, where they were probably placed during Turkish rule, on the right side of the naos of the cathedral in Gradac under the clergy composition. After the destruction of the sarcophagus, they were kept under the vault of the chapel on the left side of the temple naos, and then on the throne of the temporary altar [8].

With the name of St. Helena is associated with a miraculous cross, which she placed in the Sopočani monastery. It is assumed that the cross was in the monastery until the 1430s, and then was transferred by Despot George (Gurg) Brankovich to Hungary, from where it came to Vienna, where it was kept among the palace relics of the Habsburgs. In the 18th century particles of this cross were given to newborn princes and princesses, who wore them in silk bags around their necks [9].

Center for the veneration of St. Helen of Serbia is the Gradac Monastery, where the celebration takes place on the day of memory of St. Equal-to-the-Apostles Constantine and Helen (May 21) [10]. Nearby residents often call the monastery and its cathedral “Sveta Ela”.

Memory of St. Helena is celebrated on October 30 along with the memory of her children, St. Milutina and Dragutina.

Separate service of St. Elena is missing. She is mentioned in the service to King Milutin (October 30), written in the end. XIV - beginning V. Serbian Patriarch Daniel III, in the first stichera at Great Vespers as the mother of two saints, in the 3rd and 4th troparions of the 6th canon of the canon and in the 2nd troparion of the 8th canon as the “beautiful” and “glorious” mother of saints kings [11].

Until recently, there was no evidence of the veneration of St. Helena of Serbia outside Serbia and the dedication of temples to her was unknown.

On October 3, 2016, in the Sergius Cathedral of the Trinity-Sergius Varnitsa Monastery, the consecration of the chapel in honor of St. Elena Serbskaya [12].

Recommendations

- Margaret Eagar, Six Years at the Russian Court,

alexanderpalace.org - Peter Kurth, Anastasia: The Mystery of Anna Anderson,

1983. - Robert K. Massey, Nicholas and Alexandra,

1967 - Rappaport, H. (2008) Ekaterinburg: The Last Days of the Romanovs

, St. Martin's Press: New York. ISBN 978-0-099-52009-2. - Zeepwat, K. (2000) Romanov's Autumn

: Sutton Publishing: Stroud, UK. ISBN 0750944188. - Zeepwat, K. (2004) Camera and Tsars: The Romanov Family Album

, Sutton Publishing: Stroud, UK. ISBN 075094210X.

Hagiography

Life of St. Helena, written around 1317 by Archbishop. Pechsky Daniel II, and documentary sources paint two images that are only partially in contact with each other. The Life of Daniel is included in his collection of Lives of the Kings and Archbishops of Serbia (in which it is the only life of a woman). The same text, as an independent life, is contained in the Hilandar collection No. 482, rewritten in 1536 [13].

The author of the life, who knew St. Helena and treated her with undisguised sympathy (his work dates back to the period of the reign of her son Milutin), wrote lengthy praise of the queen’s Christian virtues, passing over the question of her religious affiliation in silence.

A number of information about Helen of Serbia is also contained in the lives of her husband and sons, written by the same author. Prose Life of the Blessed Monk. Helena" accompanies the service of Milutin in the list of the 16th-17th centuries. [14]. Brief life of St. Helen, “the wonderworker, the mistress of the Srbsk ezik,” placed under February 8. in the verse Prologue of the library of the Trinity Monastery near Plevlia, was rewritten in 1663/64 on Mount Athos [15].

early years

Strong, determined Helen, whose mother died when she was a small child, was born in Cetinje, Montenegro, and was raised primarily under the tutelage of her aunts Stana and Milica. She was educated in Russia at the Smolny Institute, a school in St. Petersburg for born girls. “She was a very sweet but simple girl, with beautiful dark eyes, a very quiet and amiable manner,” wrote Margaretta Eagar, governess to the daughters of Tsar Nicholas II. Eagar wrote that Helen, then seventeen, often came to tea with her other aunt. Princess Viera of Montenegro, and cousins. The young Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna of Russia loved her very much.[2]

Iconography

Lifetime and posthumous images of St. Helena are quite numerous. Together with her sons Dragutin and Milutin, she is represented on the icon “Apostles Peter and Paul” con. XIII century, embedded in the cathedral of St. Peter in Rome and now located in the Vatican [16], and together with Milutin - on an image of St. dating from approximately the same time. Nicholas, kept in the cathedral in Bari [17]. Images of St. Helena in monastic vestments, together with Urosh and the ktitor of the temple Dragutin, can be seen on the paintings of the Dragutin Chapel in the monastery of Djurdjevi Stupovi (1282/83) and the cathedrals in Arilje (c. 1295), Gradac (not preserved), Sopocani and Gracanica; in the last 2 cases, in the accompanying inscription it is called “St. nun." In the paintings of the Gradiste Monastery (1620) St. Helen is depicted with a crown in rich vestments.

The history of Helen Equal to the Apostles and the appearance of the icon

The saint comes from Bethany, a relatively small city in Asia Minor that was under Roman rule. Thanks to this, the girl at a young age managed to fall in love with a Roman soldier (named Costanzo Chloro) and gave birth to a son, Constantine.

Over time, his wife was offered the important post of ruler of the Roman lands, but for this he had to leave his current marriage and become engaged to the emperor’s daughter. Constantius agreed and eventually became the ruler of the western territories of the Roman Empire. This title was inherited by his son Constantine, who also became a warrior.

As a result, Constantine comes into conflict with the ruler of the eastern lands, Maximilian, and becomes the ruler of the entire empire. Christianity was legalized by his decree.

In the future, she turns to her mother to become an empress. That is why the icon of St. Helena and the icon of St. Constantine are often combined. They are also honored on the Feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross.

The icon often depicts Queen Helena with the acquired cross, which has been on earth for more than three hundred years. It is thanks to this merit that the queen is revered in many ways.

Literature

- Danilo II, Archbishop. Lives of the region and the Archbishop of Srpsky. Beograd, 1988. pp. 79-107

- Mijatoviě Ch. Ko je kraљitsa Jelena. Novi Sad, 1902;

- Hilarion (Ruvarats), archimandrite. Kraljitsa and Tsarina Srpska // Zb. Hilarion Ruvartsa: Odabrani ist. rejoice. Beograd, 1934. St. 1. pp. 8-12;

- Subotiћ G. Krajitsa Jelena Anzhujska - ktitor of the church spenik in Primorju // Historical Glasnik. Beograd, 1958. Br. 1-2. pp. 131-148;

- Pavloviě L. Kultovi faces code of Srb and Macedonian: (Historical-ethnogr. massacre). Smeredevo, 1965. P. 85-88:

- Kashanin M. Srpska kizhevnost in the Middle Ages. Beograd, 1975 (by decree);

- Naumov E. P. The ruling class and the state. power in Serbia XIII-XV centuries. M., 1976 (by decree);

- Jirechek J. K. History of Srba / Prev. J. Radonih. Beograd, 19782. Kњ. 1, 2 (as indicated);

- McDaniel Gordon L. On Hungarn-Serbian Relations in the XIII Century: John Angelos and Queen Jelena // Ungarn Jb. Münch., 1982/1983. Bd. 12. P. 43-50:

- Florya B.N. Research on the history of the Church: Old Russian. and glory Middle Ages. M., 2007. pp. 168-171.

- Dominika Gapska. “Dni pamięci świętych władczyń w kalendarzu serbskiej Cerkwi prawosławnej” // Latopisy Akademii Supraskiej, red. M. Kulczycka, U. Pawluczuk, Białystok 2013, vol. 4, s. 52-53:

Notes

- Robert K. Massey, Nicholas and Alexandra, 1967, p. 198

- Eagar, Margaret (1906). "Six years at the Russian court." alexanderpalace.org

. Retrieved January 3, 2007. - ^ a b

Zeepvat, page 56. - Alexander Bokhanov, Dr. Manfred Knodt, Vladimir Ustimenko, Zinaida Peregudova and Lyubov Tyutyunnik, translator Lyudmila Ksenofontova, The Romanovs: Love, Strength and Tragedy,

1993, p. 127. - ^ a b

Helen Rappaport, page 34 - Peter Kurth, Anastasia: The Mystery of Anna Anderson,

1983, p. 43. - Charlotte Zeepwat, Camera and Tsars: The Romanov Family Album,

2004, p. 213.

Prayers

Troparion to Venerable Helen of Serbia, Queen, tone 4

From the western country/ the holy vine of Serbia, having united,/ a well-grown branch appeared,/ the faithful princess Elena./ The red fruit of the holy son of the duo/ brought to God and the to the Serbian, / finally left all the vanity of the world / and you were joined to the venerable: / with boldness to the Lord Pray for everyone/ to grant universal peace// and for the Slovenian sons to be saved.

Translation: From a western country, grafted onto the holy Serbian vine, you have become a beautifully grown branch, blessed princess Elena. Like beautiful fruits, you brought two holy sons to God and the Serbian family, in the end you left all the vanity in the world and joined the saints, with boldness you prayed to the Lord of all to grant peace to the earth and to save the sons of the Slavs.

Source of the article: https://azbyka.ru/days/sv-elena-serbskaja

Life

Saints Stefan Milyutin, his brother Dragutin (monastically Theoktist) and their mother Elena

Saint Stephen was the youngest son of King Stefan - Urosh I and the grandson of the first-crowned King Saint Stephen (September 24).

He ruled Serbia from 1275 to 1320. Stefan Milyutin received the throne from his elder brother Dragutin, a faithful Christian, who, after a short reign, transferred power to his brother, and he, having fallen in love with hermithood, secluded himself in Srem, where he performed secret exploits in a pit-grave dug with his own hands. In his righteous life, Saint Dragutin worked hard to convert the Bogomil heretics to the true faith. His death followed on March 2, 1316. Saint Stefan Milutin, having become king, courageously, in word and deed, often with arms in hand, defended the Orthodox Serbs and other peoples of the same faith from numerous enemies. Pious Stephen did not forget to thank the Lord for all His benefits. He built more than 40 churches, many monasteries and hospice houses. The saint took special care of the Athonite monasteries.

When the Serbian kingdom fell, the monasteries remained centers of national culture and Orthodoxy among the Serbian people. Saint Stephen died on October 29, 1320 and was buried in the Bath monastery. Two years later his incorruptible relics were discovered.

Saint Helena, the pious mother of her holy sons, after the death of her husband, devoted her entire life to godly deeds: she built houses for impoverished villagers, and established monasteries for those who wanted to live in purity and virginity. Near the city of Spicha, she erected the River Monastery and endowed it with land. Before her death, Saint Helena accepted monasticism and departed to the Lord on February 8, 1306.

What do they ask for before the image?

During her lifetime, the Queen of Serbia took care of the poor, the wretched, and the lonely. It is customary to ask her for a variety of different things. Most often, prayers are devoted to requests for the granting of family well-being.

Various prayers are addressed to the Queen of Serbia:

- They ask like a mother for her children. It helps to protect the child, guide him on the true path, and enlighten him.

- They beg for children. Women from all over the world who cannot conceive a child come to the relics. Touching the cancer brings comfort and humility.

- Women ask for a good husband, a happy and peaceful family life. For those who are already married, the reverend helps to improve the atmosphere within the family.

Before the face they ask for the healing of relatives and friends. The saint is especially merciful to those whose relatives are terminally ill. It helps ease the pain before death.

The nuns love Saint Helena very much; they bow their heads before the face of their mentor in order to gain faith in their own strengths and to be strengthened by the example of a pious and righteous life.

Excerpt characterizing Elena Petrovna Serbskaya

Judging by the moderately calm and friendly tone with which the French emperor spoke, Balashev was firmly convinced that he wanted peace and intended to enter into negotiations. - Sire! L'Empereur, mon maitre, [Your Majesty! Emperor, my lord,] - Balashev began a long-prepared speech when Napoleon, having finished his speech, looked questioningly at the Russian ambassador; but the look of the emperor's eyes fixed on him confused him. “You are embarrassed - come to your senses,” Napoleon seemed to say, looking at Balashev’s uniform and sword with a barely noticeable smile. Balashev recovered and began to speak. He said that Emperor Alexander did not consider Kurakin’s demand for passports to be a sufficient reason for war, that Kurakin did so arbitrarily and without the consent of the sovereign, that Emperor Alexander did not want war and that there were no relations with England. “Not yet,” Napoleon interjected and, as if afraid to give in to his feelings, he frowned and nodded his head slightly, thereby letting Balashev feel that he could continue. Having expressed everything that was ordered to him, Balashev said that Emperor Alexander wants peace, but will not begin negotiations except on the condition that... Here Balashev hesitated: he remembered those words that Emperor Alexander did not write in the letter, but which he certainly ordered that Saltykov be inserted into the rescript and which Balashev ordered to hand over to Napoleon. Balashev remembered these words: “until not a single armed enemy remains on Russian land,” but some complex feeling held him back. He could not say these words, although he wanted to do so. He hesitated and said: on the condition that the French troops retreat beyond the Neman. Napoleon noticed Balashev's embarrassment when uttering his last words; his face trembled, his left calf began to tremble rhythmically. Without leaving his place, he began to speak in a voice higher and more hasty than before. During the subsequent speech, Balashev, more than once lowering his eyes, involuntarily observed the trembling of the calf in Napoleon’s left leg, which intensified the more he raised his voice. “I wish peace no less than Emperor Alexander,” he began. “Isn’t it me who has been doing everything for eighteen months to get it?” I've been waiting eighteen months for an explanation. But in order to start negotiations, what is required of me? - he said, frowning and making an energetic questioning gesture with his small, white and plump hand. “The retreat of the troops beyond the Neman, sir,” said Balashev. - For Neman? - Napoleon repeated. - So now you want them to retreat beyond the Neman - only beyond the Neman? – Napoleon repeated, looking directly at Balashev. Balashev bowed his head respectfully. Instead of the demand four months ago to retreat from Numberania, now they demanded to retreat only beyond the Neman. Napoleon quickly turned and began to walk around the room. – You say that they require me to retreat beyond the Neman to begin negotiations; but they demanded of me in exactly the same way two months ago to retreat beyond the Oder and Vistula, and, despite this, you agree to negotiate. He silently walked from one corner of the room to the other and again stopped opposite Balashev. His face seemed to harden in its stern expression, and his left leg trembled even faster than before. Napoleon knew this trembling of his left calf. “La vibration de mon mollet gauche est un grand signe chez moi,” he said later. “Such proposals as clearing the Oder and the Vistula can be made to the Prince of Baden, and not to me,” Napoleon almost cried out, completely unexpectedly for himself. – If you had given me St. Petersburg and Moscow, I would not have accepted these conditions. Are you saying I started the war? Who came to the army first? - Emperor Alexander, not me. And you offer me negotiations when I have spent millions, while you are in an alliance with England and when your position is bad - you offer me negotiations! What is the purpose of your alliance with England? What did she give you? - he said hastily, obviously already directing his speech not in order to express the benefits of concluding peace and discussing its possibility, but only in order to prove both his rightness and his strength, and to prove Alexander’s wrongness and mistakes. The introduction of his speech was made, obviously, with the aim of showing the advantage of his position and showing that, despite the fact, he accepted the opening of negotiations. But he had already begun to speak, and the more he spoke, the less able he was to control his speech. The whole purpose of his speech now, obviously, was only to exalt himself and insult Alexander, that is, to do exactly what he least wanted at the beginning of the date. - They say you made peace with the Turks? Balashev tilted his head affirmatively. “The world is concluded...” he began. But Napoleon did not let him speak. He apparently needed to speak on his own, alone, and he continued to speak with that eloquence and intemperance of irritation to which spoiled people are so prone. – Yes, I know, you made peace with the Turks without receiving Moldavia and Wallachia. And I would give these provinces to your sovereign just as I gave him Finland. Yes,” he continued, “I promised and would have given Moldavia and Wallachia to Emperor Alexander, but now he will not have these beautiful provinces. He could, however, annex them to his empire, and in one reign he would expand Russia from the Gulf of Bothnia to the mouth of the Danube. “Katherine the Great could not have done more,” said Napoleon, becoming more and more excited, walking around the room and repeating to Balashev almost the same words that he said to Alexander himself in Tilsit. – Tout cela il l'aurait du a mon amitie... Ah! Quel beau regne, quel beau regne! - he repeated several times, stopped, took a golden snuffbox out of his pocket and greedily sniffed from it. – Quel beau regne aurait pu etre celui de l'Empereur Alexandre! [He would owe all this to my friendship... Oh, what a wonderful reign, what a wonderful reign! Oh, what a wonderful reign the reign of Emperor Alexander could have been!] He looked at Balashev with regret, and just as Balashev wanted to notice something, he again hastily interrupted him. “What could he want and seek that he would not find in my friendship?..” said Napoleon, shrugging his shoulders in bewilderment. - No, he found it best to surround himself with my enemies, and who? - he continued. - He called to him the Steins, Armfelds, Wintzingerode, Bennigsenov, Stein - a traitor driven out of his fatherland, Armfeld - a libertine and intriguer, Wintzingerode - a fugitive subject of France, Bennigsen somewhat more military than the others, but still incapable, who could not do anything to do in 1807 and which should awaken terrible memories in Emperor Alexander... Let’s suppose, if they were capable, one could use them,” continued Napoleon, barely managing to keep up with the words that constantly arise, showing him his rightness or strength (which in in his concept were one and the same) - but even that is not the case: they are not suitable for either war or peace. Barclay, they say, is more efficient than all of them; but I won’t say that, judging by his first movements. What are they doing? What are all these courtiers doing! Pfuhl proposes, Armfeld argues, Bennigsen considers, and Barclay, called to act, does not know what to decide on, and time passes. One Bagration is a military man. He is stupid, but he has experience, an eye and determination... And what role does your young sovereign play in this ugly crowd. They compromise him and blame him for everything that happens. “Un souverain ne doit etre a l'armee que quand il est general, [The sovereign should be with the army only when he is a commander,” he said, obviously sending these words directly as a challenge to the sovereign’s face. Napoleon knew how much Emperor Alexander wanted to be a commander. – It’s already been a week since the campaign began, and you have failed to defend Vilna. You are cut in two and driven out of the Polish provinces. Your army is grumbling... - On the contrary, Your Majesty, - said Balashev, who barely had time to remember what was said to him, and with difficulty following this fireworks of words, - the troops are burning with desire... - I know everything, - Napoleon interrupted him, - I’m all I know, and I know the number of your battalions as surely as mine. You don’t have two hundred thousand troops, but I have three times that much. “I give you my word of honor,” said Napoleon, forgetting that his word of honor could not have any meaning, “I give you ma parole d’honneur que j’ai cinq cent trente mille hommes de ce cote de la Vistule.” [on my word of honor that I have five hundred and thirty thousand people on this side of the Vistula.] The Turks are no help to you: they are no good and have proven this by making peace with you. The Swedes are destined to be ruled by crazy kings. Their king was mad; they changed him and took another - Bernadotte, who immediately went crazy, because a crazy person only being a Swede can enter into alliances with Russia. - Napoleon grinned viciously and again brought the snuffbox to his nose. To each of Napoleon’s phrases, Balashev wanted and had something to object to; He constantly made the movement of a man who wanted to say something, but Napoleon interrupted him. For example, about the madness of the Swedes, Balashev wanted to say that Sweden is an island when Russia is for it; but Napoleon shouted angrily to drown out his voice. Napoleon was in that state of irritation in which you need to talk, talk and talk, only in order to prove to yourself that you are right. It became difficult for Balashev: he, as an ambassador, was afraid of losing his dignity and felt the need to object; but, as a person, he shrank morally before forgetting the causeless anger in which Napoleon, obviously, was. He knew that all the words now spoken by Napoleon did not matter, that he himself, when he came to his senses, would be ashamed of them. Balashev stood with his eyes downcast, looking at Napoleon’s moving thick legs, and tried to avoid his gaze.

Links

- [pages.prodigy.net/ptheroff/gotha/russia.html The Romanovs on the Gotha website]

- [pages.prodigy.net/ptheroff/gotha/yugoslavia.html Karageorgievici on the Gotha website]

| Karageorgievici | ||||||||

| Karageorge Petrovich 1762-1817 wife Elena Jovanovic | Alexa Karageorgievich 1801—1829 | Georgiy Karageorgievich 1827—1884 | Alexa Karageorgievich 1858—1920 | |||||

| Bozhidar Karageorgievich 1862—1908 | ||||||||

| Aleksandar Karageorgievich 1806-1885 wife Persida Nenadovich | Peter I Karageorgievich 1844-1921 wife of Zorka of Montenegro | Elena Petrovna Serbskaya 1884-1962 husband Ioann Konstantinovich Romanov | see further: Romanovs | |||||

| Georgiy Karageorgievich 1887—1972 | ||||||||

| Alexander I Karageorgievich 1888-1934 wife Maria Hohenzellern | Peter II Karageorgievich 1923-1970 wife of Alexandra Oldenburg | Alexander Karageorgievich 1945 first wife Maria-Gloria (marriage: 1972-1983) second wife Katarina Batis | Peter Karageorgievich 1980 | |||||

| Filip Karadjordjevic 1982 | ||||||||

| Alexander Karageorgievich 1982 | ||||||||

| Tomislav Karageorgievich 1928—2000 | ||||||||

| Andrey Karageorgievich 1929—1990 | ||||||||

| Arsen Karageorgievich 1859-1938 wife Aurora Pavlovna Demidova | Pavel Karageorgievich 1893—1976 | Alexander Karageorgievich 1924—2016 | ||||||

| Nikola Karageorgievich 1926—1954 | ||||||||