Definition

Iconic writing is understood as the creation of sacred images. This is how the Byzantines saw it, and the word “icon” (“εἰκών”, or likeness, image) comes from the Greek language. Initially, in the tradition of the Christian East, “icon painting” meant both the writing of images of saints on boards and the creation of monumental images - frescoes on the walls of churches, mosaics.

Subsequently, since the term “icon” in the narrow sense began to mean a relatively small image, the concept began to be attributed more to images, most often written on a board.

Word stress

All authors of modern dictionaries indicate that it falls on the first syllable. However, all words with the same root, including “icon”, the derivative of which is “ and hemp”, have stress on other syllables, but not on the first one: “iconop and setts”, “iconic ” , “iconography ” . In addition, the word “ik o na” itself in its Greek version has stress on the second syllable. It is from here that the word is often used as “ik o nopis”. This option is given, for example, in the well-known scientific publication “Orthodox Encyclopedia”.

Story

The Jews, among whom Jesus Christ , did not have a tradition of images not only of God, but even of people - such images were absolutely prohibited.

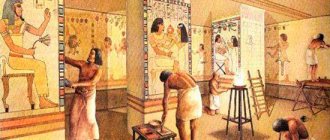

Therefore, the tradition of creating icons goes back to the Greeks, Romans, and other pagan peoples. Their artists have long been able to convey the volume, texture, and individuality of the depicted person.

The masterpieces of such painting are, for example, the so-called “Fayum portraits” created using the encaustic technique (painting with molten wax), images on the tombs of the inhabitants of Egypt dating back to the 1st-3rd centuries. They are very realistic, and the colors remain bright even to this day.

Icon as a portrait?

The encaustic technique was also very popular among Christians . So, among the images of the monastery of St. Catherine on Sinai there are images of Christ, Apostle. Peter, also made with wax paints, realistically conveying personality traits.

Christ Pantocrator First half of the 6th century. 84 × 45.5 × 1.2 cm Monastery of St. Catherine, Sinai, Egypt. Encaustic icon from the mid-6th century depicting Jesus Christ in Pantocrator iconography. The oldest known icon painting of Christ. The icon was created in Constantinople in the middle of the 6th century and sent by Emperor Justinian as a gift to the Sinai monastery, for which he was building a basilica and fortified walls at that time. The icon was discovered in the monastery in the 19th century. It was established that presumably in the 13th century the icon was renewed (drawn) with tempera painting. The original wax surface was cleaned during the restoration of the icon in 1962.

Iconography is a sacred fine art

One of the most important types of Christian art is icon painting.

First of all, it should be noted that icon painting is not painting, it is the most ancient skill of depicting holy images, crosses and faces of saints. Everything is different here. Thus, the accessories of an Orthodox church - church utensils, which can be purchased in the online store https://blagvist.com.ua/ - have a complex symbolic meaning and a long history of the origin of the ritual. A painter paints pictures, bringing to life his creative fantasies and ideas, while an icon painter creates a sacred icon, which personifies a heavenly spiritual image intended for prayer and praise. The icon serves as an object of reverent worship and therefore everything in it should be extremely serious, devoid of creative inventions. When painting an icon, the icon painter is guided not by personal thoughts and desires, but exclusively by Christian tradition. Holy Scripture and ancient traditions dictated to the icon painter the rules for depicting a sacred icon, not excluding some creative freedom in combining images.

The history of icon painting dates back to ancient times, the first centuries of Christianity; some images that have come down to us from those times are rather symbolic. The first Christians portrayed God as the good shepherd. Persecuted and persecuted, they hid from the pagans in underground caves; it was in such catacombs in Rome that the most ancient images were discovered. This can be called the first stage of Christianity. At the next stage of Christian icon painting, “Byzantine,” imagery appears, ancient art is modified, under the influence of various cultural trends, images become serious, covered with clothes and precious stones. The image of the Savior acquires long hair, a beard and a halo, with which it is currently depicted. During this period, Christian art actively developed, new church holidays appeared, and new beautiful icons were created in their honor.

At this time, the art of icons does not limit the depiction of a holy image exclusively on a board; it can be an image on paper, a wall, a metal surface, or on everyday church items; The icon can also be engraving, embroidery or mosaic. Iconography is God’s word, only it is expressed and narrated not in verbal form, but on a plane. If we consider an icon as a work of art, as a masterpiece of Christian fine art, then, of course, not a single, even the most picturesque, painting will surpass icon painting, first of all, in its spiritual meaning. The technical process of creating icons itself is quite complicated; it is a whole school of icon painting, which has its own personal language and literacy. As in any form of art, there are canons and rules that should be followed; as in any science, there are immediate basics and stages of learning. Depending on the materials, the icon painting technique and reproduction techniques are completely different. The oldest technique is passed down strictly from generation to generation, so every novice master must adhere to the existing rules. Under no circumstances should the image of the holy image and the algorithm for its creation be violated.

The role of the icon in the life of Christian society is infinitely important. If we recall all the rituals that have marked a sad or happy mark in a person’s life, then each of them, according to the old tradition, is accompanied by the presence of a sacred icon: a wedding, a wedding, the baptism of a child, or a last farewell. The Church sees in the icon, first of all, the personification of a sacred image and the image of the eternal Christian faith, and not a form of art; this is what distinguishes the Christian visual stronghold from the creative painting school.

Tags:

- icon painter

- iconography

- writing icon

- the role of the icon

- Christianity

Latest materials in this section:

- What unusual museums in Russia are worth visiting?

Museum of Garbage "MU MU" Museums, exhibitions, art galleries - remembering this, most often in the head...

2022-01-23

- Works of the sculptor Fyodor Gordeev

Fyodor Gordeevich Gordeev (1744-1810) Among the students of the Russian Academy of Arts in the early years ...

2022-01-14

- Acrylic worlds: Elena Ksanti and her art therapy

Life Line Contemporary painting is paintings in which reality is reflected through immersion...

2021-12-25

- Joachim Govaerts from the Kamphuizen dynasty of artists

Koning, Cornelis Portrait of Dirk Raphaelison Kamphuisen (painted between 1627-1633) In the International...

2021-11-09

- Writing technique. How to understand the picture

Nuances of perceiving art “They use paints, but write with feelings,” said the French living...

2021-10-28

↓↓ Look below for thematic similarities (Related materials) ↓↓

| Next > |

Technique

From the 9th century creators of icons switched to the so-called layered painting. It means that:

- colors never mix with each other; therefore, the icons do not have halftones, or colors such as pink, gray, or other similar ones;

- paints are applied in layers - with a new layer only after the previous one has completely dried.

This is how the principle of “unmerged connection” is realized even in the paints themselves used by the icon painter.

Natural mineral pigments

From the 9th century Icon painters are beginning to increasingly use tempera, that is, powder paints based on minerals diluted in egg yolk, sometimes with the addition of oil. Among the most commonly used minerals are:

- ocher, red and yellow; this is hematite or limonite (the so-called brown iron ore) with clay; red ocher is often used to paint the tunic of Christ, the robe of the Virgin Mary, and yellow ocher is used to make the background of an icon;

- cinnabar is a bright red mercury mineral;

- lapis lazuli is a blue mineral, many others.

Boards

The board for the icon is prepared in a special way:

- first, a small recess is made for the image itself, called the “ark”;

- fabric - pavolok - is glued onto it;

- gesso is applied on top of it - a special primer based on alabaster or chalk.

Interesting fact

Many experts say that such preparation of the board serves for greater strength and safety.

However, priest Pavel Florensky in his work “Iconostasis” draws attention to the fact that the most ancient icons were created not on a board, but not on a stone, which is not accidental: it is this material that most clearly symbolizes eternity, the immutability of the heavenly world. Therefore, in the preparation of the board one can also see a kind of symbolic “transformation” of wood into a stone wall - it is even “plastered” in a similar way.

The process of creating an icon

“Layering” is not only a technique for applying paints, but also a special order for painting an image:

- first, on an already primed board, the artist makes a “draw”, or preliminary drawing, outline;

- after this, the background is made: it can be gilded, when the thinnest leaves of gold are glued to the ground, or simply painted;

- the next stage is the details of the attire of the person depicted, the elements of architecture and nature surrounding him;

- The most important part of the image, the face, was painted last.

Photo by Asya Krasnova

Iconography. Iconostasis. Ikorta

Iconography

[icon painting], a type of painting whose task is to create sacred images - icons. Despite the fact that in the Eastern Christian tradition the Greek. The word ɛἰkῴv (image, likeness, image) is a general name for sacred images (see articles Monumental painting, Fresco, Mosaic, Miniature); as works of art, an icon written on a board is usually considered as a prayer image.

On the development of artistic styles, see the corresponding sections of the articles “Russian Art of the X-XXI Centuries”, “Art of Ukraine and Belarus. XVI-XVIII centuries." (PE. T.: ROC), as well as articles Albanian Orthodox Church, Bulgarian Orthodox Church, Byzantine Empire, Greece, Georgian Orthodox Church, Romanian Orthodox Church, Serbian Orthodox Church, etc.

Method in I.

The icon, which has existed for almost 2 millennia, owes its longevity largely to the conservatism of painting technique, carefully preserved by icon painters until the present day. To understand the specifics of icon painting technique, it is important that the variety of techniques and the richness of the individual handwriting of the artists - the artistic manner of each of the masters - are combined with the constancy of the layer-by-layer painting method, which is an indicator of the stability of the painting system.

The layer-by-layer painting method, known since ancient times, is used to work in any colorful techniques (tempera, oil, fresco, watercolor). As a so-called medieval method, it serves as a means of expression in a special system of painting, which is characterized by reverse perspective, taking into account only distortions of the “close foreground”, while modeling chiaroscuro and color perspective were not used, color contrast was preferred to tonal, and smooth color transitions were not always considered expressive, used color differentiation, selected color dominants based on general local coloring.

The layer-by-layer method is the opposite of the method of mixing fresh, uncured paints on a painting surface, which leads to blurring of the boundaries between color fields. Thus, wanting to convey the originality of the Byzantine painting technique in comparison with the Renaissance, R. Byron and D. Talbot Rice ( Byron R., Talbot Rice D. The Birth of Western Painting. L., 1930. P. 101)

. When layering paints, an immutable condition must be observed - each subsequent layer is applied after the previous one has completely dried, thus not allowing fresh, uncured paints to mix on the surface of the icon. Paint layers differ in density depending on the recipe for preparing mixtures, in which the ratio of the binder and the amount of pigment vary. The size of the particles of the latter could be either very large or small. The texture of the paint surface depended on the ability to prepare colorful mixtures and apply them. Pasty and dense layers alternated in a certain sequence with translucent and glaze layers.

The layering method is not associated with a specific paint technique or with one type of binder, and in this sense it is universal. Thus, it was applicable both for the implementation of enormous monumental tasks and for working with miniature forms. And the main requirement for the binder was its rapid drying. Apparently, the transition to the layer-by-layer method, convenient when working with quick-drying paints, influenced the technique of painting, and primarily on painting with wax paints. It was believed that most of the icons of the pre-iconoclastic period (for example, “Christ Pantocrator”, “Apostle Peter”, “Our Lady Enthroned, Saints Theodore and George”, “Ascension” - all in the monastery of Martyr Catherine at Sinai; “St. John Forerunner", "The Virgin and Child", "Saints Sergius and Bacchus", "Martyr Plato and the Unknown Martyr" - all in the Museum of Western and Eastern Art, Kiev, etc.) were created using the encaustic technique (a labor-intensive technique that requires constant wax heating). However, studies have shown that these icons, despite the use of wax paints, were painted using a layer-by-layer method, which encaustic eliminates: sequential application of paint layers that preserved traces of brush work was possible only with the “cold” technique, when each subsequent layer was applied to an already completely dried lower. Obviously, it was the search for a simpler technology that led artists to painting with wax paints mixed with a solvent (turpentine), which allows them to maintain wax paints for a long time in a liquid state without heating. This type of wax painting is commonly called wax or “encaustic” tempera.

The turning point for Israel was the era of iconoclasm, which ended in 843 with the Triumph of Orthodoxy and the emergence of new aesthetic norms. The mystical side of the icon, which icon admirers mentioned in disputes, forced artists to reconsider many of the technical requirements for creating an iconographic image. After 2 centuries of iconoclasm, wax painting did not revive on the same scale: this semi-antique technique was destroyed along with the generation of artists who owned it. Perhaps, before the start of iconoclasm, this technique was to a large extent associated with the tradition of Iconoclasm, and not secular art, otherwise it, like mosaics, could have found its place in the palaces of iconoclast rulers.

Since the 9th century, the technique of painting icons has been associated exclusively with tempera. In the strict sense of the word, tempera is a method of mixing paint with a binder. The transition to tempera as a simpler painting technique could be due to the need for large-scale restoration of the iconographic fund. In addition, tempera, to a greater extent than the wax technique, contributed to the creation of an ideal “miraculous” texture. Probably, the formation of this idea was influenced by the legend about the Image of the Savior Not Made by Hands,

transferred from Edessa to Constantinople in 916. The compilation of a church service for him “voiced” the mystical ideal of the era and was also intended to help get closer to it visually, standing “face to face.” In Middle Byzantine art, one of the branches of which was the art of Slavic countries, including Russian art of the pre-Mongol period, special painting techniques were developed that allowed the icon painter to embody in paint a great idea - the creation of the image of God.

Even in the technique of wax tempera, two particularly important points were identified that determine the coloristic properties of the icon: the appearance of a white primer, which increased the light scale of color, and the division of colors into layers, which changed the principle of mixing man-made color (on the palette) with an optical one, with an ordered colorful structure. Layer-by-layer painting allows you to reveal the spatial qualities of color, because The passage of light through differently colored media (layers of paint on a binder) creates the main color effect and the visual impression that warm color tones come forward and cool colors recede.

The white primer that began to be used increased the brightness of the reflected radiation, revealing all the diversity of the color spectrum. Various background pads - warm or cold - gave direction to the reflection process, absorbing one or another part of the spectrum, and multi-colored layers built up in a certain order distributed this color scale in space. The method of layer-by-layer application of colors onto white, smooth, often polished soil was the “causative agent” of luminosity, thanks to it the light more actively penetrated deeper. This method was a specific optical system, the physical basis of which from a scientific point of view has not been fully elucidated. Obviously, the properties of the multilayer paint surface made it possible to “organize” the work of external physical light. O. Demus

emphasized that in Byzantine art one of the main tasks was to transform external light into a visual medium

(Demus O. Byzantine Mosaics Decoration. L., 1947. P. 35–36).

Layer-by-layer application of paints changes the principle of color mixing. In general, color is no longer the result of their merging and transformation into an indistinguishable alloy, as in encaustic, but an ordered colorful structure, the essence of which is the unity and separateness of colors - properties that correspond to the main principle of Byzantine aesthetics of “unmerged connection”. Medieval artists knew several ways to mix paints to create complex colors. The first is mechanical, when the required set of pigments is mixed with a binder to create a certain color. The structural expressiveness of Byzantine painting can be traced at the level of the pigment composition of the mixture, that is, it is practically not perceived by the eye as a complete whole. As a rule, small pigments, sometimes dust-like, lie in the lower layers, and larger ones in the upper layers. The Byzantine artist mastered the art of “controlling” the distribution of pigments on the surface of the paint layer, using intermediate glazes that helped him “fix” especially large particles, on which the color of the color depended. Therefore, Byzantine masters especially valued optical mixing methods. In color science, one of these methods is called “incomplete” spatial color mixing. It depends on the texture of the painting surface, which can be strokes intersecting in different directions, echoing the relief of the form or, conversely, unrelated to the form, small and short, thin and elongated. Colorful layers, applied one on top of the other, could merge due to their imperceptible transitions, giving rise to the illusion of mixing. Much depended on the ability to apply layers thinly, working with small brushes. In the intervals between strokes of the upper layers, the lower layers are visible, thereby creating the effect of their unity. Another method of mixing - the so-called illusory - is that when using large pigment crystals located in the lower layers of painting, the paint of the upper layers “rolls off” their sharp edges without covering them. Therefore, it seems that large, intensely colored crystals of minerals such as glauconite or lapis lazuli are found in the upper, bleached layers as impurities, which is deceptive. Thanks to this, external physical light, refracting on their sharp edges, creates a play of colors, enlivening the color.

There are quite a few attempts to explain the high aesthetic merits of Byzantine painting based on the special optical properties of the technique. For the Byzantine artist, aware of the transformative power of Divine light, mastering in practice the process of interaction between physical light and matter, its origin through matter, became a condition for the appearance of form and the manifestation of color in I.

Admission to I.

- this is the order according to which various colorful elements are layered onto the pictorial surface: graphic and pictorial. Its simplest, “abbreviated” version was 3-layer cursive, in which dark and light graphic cuts were applied on top of the main color tone. The work order of a medieval artist can be reconstructed thanks to manuals on painting techniques (“Schedula diversarum atrium” by St. Theophilus, late 11th – early 12th centuries; “Il libro dell’arte o Trattato della pittura” by Cennino Cennini, late 14th century; “Erminia” by Hierom Dionysius Furnoagrafiot, ca. 1730–1733 – despite its late date, the terminology of “Erminia” can be used to most accurately describe the techniques of Byzantine and Old Russian painting). The scheme of the icon painter’s work, corresponding to the medieval painting method, contains several successive stages. First of all, the artist makes a “sketch of the image” on a white primed board, applying a preliminary drawing with a brush with liquid black (less often colored) paint (in an icon, unlike mural painting, it was rarely duplicated with scratched graphite). Then he begins to gild the background, “planting” gold or silver, finely forged leaves on a special glue or varnish. It was “leaf” (in the terminology of Russian jewelers) gold or silver. It differed from the created one (i.e., ground in “creat” together with a binder) not only in its shiny and smooth texture, but also in its economy. The gold on the backgrounds of the icons was polished, so that the “overlapping” joints of the glued leaves were not visible. Under the gold, the icon painter could put a special colored primer - brown bolus, or orange lead, or yellow ocher, but more often the gilding process in Byzantine and Old Russian icons did not require this technology. Sometimes gold covered the entire surface prepared for painting, especially in miniature forms, and then the colors acquired increased brightness. The backgrounds of icons were not always gold. They could be painted most often yellow, but also light green, blue, light brown, bright red, and white. Sometimes the design of the backgrounds imitated the ornamentation of the metal frame or enamels using painterly means. Often the same role - imitation of frame-setting - was played by colored or gold fields of icons, decorated either with inscriptions or medallions with images of saints. The depiction of architectural details, landscape and clothing in I. also obeyed a certain layer-by-layer system, but in contrast to the painting of the face, painting here was less developed. A single average tone was used as a background, on the basis of which 1 or 2 colors were created. White was added to the middle tone and a lightened color was obtained, which they began to layer on the surface of the main tone, simulating the growth of a three-dimensional form. It was completed with whitewash for the spaces, which formed a plastic volume. In the landscape these were slides, i.e. flat stepped tops, in architecture - the structural elements of a building, in clothing - the bend of the folds flowing around the human figure. But, as a rule, the artist was not content with such meager modeling and prepared another, more whitened, color scheme, which he placed under the white spaces, and then the surface of the painting began to seem like a multi-layered color scale. In addition, icon painters loved to make colored spaces by adding admixtures of various crystalline pigments such as ultramarine, lapis lazuli, glauconite or cinnabar to the white, or glazed the white spaces with light and thin layers of color. Optical examination helps to distinguish when pigment crystals lie inside the layer in the form of an impurity, and when on the surface in the form of glaze. In working with spaces, the master’s artistic talent was revealed, his ability to create warm (pinkish) spaces on cold (blue, green) clothes and cold (bluish, greenish) spaces on warm (cherry, raspberry-lilac) clothes. The artist had many such options, and everything depended on his talent, adherence to tradition and the artistic environment in which his work developed. One of the most expressive and modern elements of Byzantine painting was the system of constructing the face. Painting styles that changed over several centuries were, as a rule, accompanied by a change in the figurative structure, the predominance of certain physiognomic types, requiring improvement of technical techniques in accordance with new aesthetic standards. At present, it remains a mystery to scientists on what principle was used to select the techniques that were most preferable in a given era, and what is the reason for their replacement and the appearance of techniques borrowed from other painting techniques.

The principle of modeling the face, based on a strictly ordered system, was perfectly developed in pre-iconoclast history using the technique of layer-by-layer wax painting. A classically developed layer-by-layer system is represented by the painting of the face of Christ Pantocrator on an icon from the VMC monastery. Catherine in Sinai. The main background is a bright yellow spacer, which becomes almost invisible in the completed whole and serves only optical purposes - this detail will be characteristic of all Middle Byzantine, including Russian pre-Mongol painting. The noble light tone of ivory visible to the eye is the 2nd modeling layer. It is applied in several stages and differs in thickness and color, which indicates its correlation with the form. The modeling of the convex parts of the form is completed with pure whitewash “lights”, and the deepening of the form is characterized by 2 shadow colors: gray, grayish-olive, preparing the eye for a gradual transition to the dark color of the beard and eyebrows, and light purple, which serves as a blush and is different faithfulness to nature in the rendering of lips and eyelids.

Observations of color and tonal differences in medieval layered painting served as the basis for the scientific classification of techniques in writing faces. The “sankir” and “non-sankir” techniques and several of their modifications are known: combined, non-contrast and contrast sankir. There is a special order for applying the layers: on the preliminary internal drawing of the face, which in the completed image was usually hidden by the upper paint layers (in some cases, the artists took into account the effect of the drawing shining through the upper layers, then the lines of the drawing could play the role of a shadow), a spacer (“proplasmos” was applied ) – “sankir” of Russian icon painters, i.e. background layer. The following layers were layered on top of it.

The beginning of the artist’s work on the face was the choice of color and texture of the lining layer – “sankirya”: dark or light, translucent or dense. The lining layer on the white primer served as the basis for subsequent modeling. Depending on its coloristic and tonal properties, the artist chose the further course of work. For example, on top of green, olive, brown or even dark purple tones, which absorb light to a large extent, the master could build up warm and light layers, often mixing them with a large amount of white, helping to visually lift and contrast the image. This method required lengthy and detailed study and, judging by the abundance of monuments, was loved by Byzantine masters. It went back to the techniques of ancient painting from the era of its greatest flowering from the 3rd to the 2nd centuries. BC (II and III Pompeian style).

The artist’s work could also be based on a different principle: the initial light interlining layer, luminous in nature, forced more attention to be paid to the shadow parts of the form. Light, often less detailed surfaces left a feeling of “miraculous” primordial nature and permeated with light. There were combinations of different techniques.

In cursive writing, the spacer could remain in the face with the main “flesh” tone, and in more detailed writing it could be covered by the upper layers (in whole or in part), but was visible in the shadows. The gasket was either “solid”, composed on the basis of various ocher colors with the addition of cinnabar white, or conventional in color, i.e. far from the natural appearance (green, olive-marsh, dark brown), composed of glauconite or a mixture of various yellow ocher with black coal or even blue ultramarine and azurite. In the latter case, the dark pad played the role of shadows along the oval of the face and the shadow parts of the volumetric shape (near the nose, around the mouth, in the eye sockets and on the bridge of the nose). The repeated drawing of facial features was applied over the spacer with brown or olive paint and did not always strictly follow the lines of the internal drawing, which were more neat in execution than the lines of the preliminary drawing. In the final stages of work on the face, the drawing was repeatedly refined with a darker tone - brown and black, and in places of contact with blush - cinnabar or cherry.

The shadow color scheme, or “shadow frame,” of the face, directly related to the previous stage (repeated drawing of features), often merged with the drawing, was its thickening, a kind of shading, and therefore coincided with it in color. The shadows were worked on several times at different stages of work on the face, especially with light “flesh” layers. Melting (“glikasmos”), or “ohrenie”, is a layer that was applied over the gasket on the “strong” ones, i.e. protruding parts of the form so that in the recesses and shadows the gasket does not overlap. The melt is lighter and warmer than the lining due to the addition of white and cinnabar to its color. With a small scale of miniature faces or with a not very detailed painting system, melting acquired the meaning of a basic color (“flesh”) tone. Then its color was different from the lining and was based on white, cinnabar and light ocher. But in large “main images” the smelting served as a preparation for the lighter upper layers, and then its color could contain lining pigments – glauconite greens and charcoal mixed with ocher, white and cinnabar.

“Flesh” color (“sark”, “ochre”) is a modeling layer that is even lighter than melting, lying locally, in small islands on the most protruding parts of the form. Where it did not cover the uniform, a swimming trunk was visible, from under which a pad was visible along the edges of the oval of the face. In the “flesh” color there are no longer any spacer pigments - it is a separate color, again composed of white, light ocher and cinnabar. From its mixture with the gasket, the previous color was obtained - melting. Whitening strokes of “highlights” were applied on top of the “flesh” color. Sometimes a light bleaching glaze was laid between them. As a rule, this stage of creating an iconographic image is characteristic of a painting style that uses not only color, but also tonal contrast.

The blush was either adjacent to the “flesh” color and applied on top of the swimsuit, along the padding itself, or slightly covered the “flesh” color. It was a mixture of cinnabar with a small amount of light ocher or white. Blush was applied to the cheeks, shadow parts of the forehead and neck (creating the effect of “warm” shadows), lips and the ridge of the nose. On the upper, brighter lip, the blush contained almost pure cinnabar, on the lower lip there was a mixture of paint. On the ridge of the nose, the blush looked like a series of pink-red lines of increasing color intensity. Often the blush merged with the shadows that accompanied the brown contours, which gave the painting a special harmony.

Whitening highlights, or “sveta”, completed the most convex parts of the form. Depending on the degree of detail of the painting, pure white “lights” could be applied both to the melting and to the “flesh” color. With a particularly skillful technique, you can see additional bleaching glaze underneath them. “Sveta” are extremely varied in texture: they could be picturesque relief strokes, linear shading, or a soft, blurry spot. Often, researchers see certain stylistic trends in the way they are applied to the surface of a painting. Fundamentally, they are also connected by the ancient technique of “surface lines,” which most fully revealed the idea of creating a three-dimensional form on a plane. Therefore, they provide extraordinary scope for an experienced artist to demonstrate virtuosic techniques and, on the contrary, easily turn into a craft routine if there is a lack of training.

The icon was completed with a transparent, shiny covering layer, cooked using a special technology from vegetable oils, which Russian icon painters called drying oil, and which gave the paints a special brightness. Drying oil also protected paintings from moisture, dirt and light mechanical damage. However, after 50–80 years it darkened, absorbing soot from candles and dust from the air. They tried to “wash” the icon to update its painting, which had a negative impact on the preservation of its original layer. Judging by archaeological finds in the workshops of artists in Novgorod and Kyiv, at an early stage in the history of Russian iconography, drying oil was cooked from imported olive oil with the addition of amber; later it began to be obtained from linseed oil, widespread in Rus'.

The painting system, based on the layer-by-layer method, existed until the New Age, when the foundations of traditional icon painting underwent radical changes.

A. I. Yakovleva

Iconography of the Synodal period (XVIII - early XX centuries)

in Russia for a long time remained outside the interests of specialists as a subject not comparable with the masterpieces of icon painting of the 11th-17th centuries. Only since the mid-80s. XX century Publications began to appear that introduced icons from the 18th century into scientific circulation. XX century These works gave an idea of the national religious and artistic culture with new features of an iconographic, stylistic and technical nature.

Unusual methods of performing icons gained the right to exist already in the middle of the 17th century. Mostly, the masters of the Armory introduced into icon painting practice not only elements of “life”, but also new technical techniques. The first Russian treatises by Joseph Vladimirov and Simon Ushakov provided a theoretical basis for the renewed process of icon painting. The practical horizons of national icon painting were also expanded by foreign masters who were part of the royal workshops. These quests took on a purposeful character during the era of the reforms of Peter I. Church art went in several directions. The official one was represented by the direct participation of Western European masters, i.e. For the new churches of the new capital under construction - St. Petersburg, religious works were created within the framework of academic painting. The masters of the Armory, who still retained their influence, adhered to a compromise style, combining centuries-old techniques with elements of naturalism. And only the Old Believers and conservative circles of society in Moscow and the provinces remained committed to traditional icon painting.

Systematic research into the technique of late icon painting began to be carried out only in recent years and mainly within the walls of the State Research Institute for Restoration (GNIIR), which in the 70s of the 20th century. began to engage in icon painting XVlll – beginning. XX century For this purpose, the same tools are used as in the study of ancient icons (analysis under a microscope, radiography, special types of photography, chemical analysis, observations by art historians). Icons, or, more precisely, religious icon paintings belonging to the 1st direction, were already painted within the European tradition not only on wood, but also on canvas. The technique of their creation is practically no different from generally accepted academic painting. In the 2nd and 3rd directions, a traditional wooden panel was used as a base, reinforced with various shapes of dowels - mortise, profiled, counter, one-sided, overhead, end, “swallows”, etc. The shape of the icon board becomes more diverse (for example. , has figured boundaries defined by the frames of iconostases and icon cases of a baroque nature), although in the processing of the board the ark, husk, and sometimes the conventional 2nd ark in the form of a side along the edges of the board are preserved, but an absolutely flat surface is increasingly used.

At the next stage, the treated surface of the board was glued with pavolok using the generally accepted technology to prevent drying out and cracks. However, its use in the 18th-19th centuries. becomes almost optional or partial. This did not exclude complete covering with pavoloka. Thanks to radiography, it is possible to observe the fragmentary gluing of small patches of a heterogeneous nature, covering the most dangerous places, such as areas with knots, all kinds of cavities and mechanical damage to the wood. Later, icon painters used paper sheets, pages from books, and even newspapers instead of pavolok. Gesso soil still retains its importance. However, preference is given to gypsum gesso instead of the chalk gesso adopted in ancient icon painting.

Basically, the technique of icon painting remained the same; traces were used, which determined the iconography and composition of the work. First we did the background and minor details, then we moved on to the personal. Along with a plain (ocher) coating, gold was often used for the background, both sheet and melted, which was applied to a reddish polyment. Created gold was more often used to develop various parts, incl. vestments. Backgrounds were often “enriched” with additional decor. The craftsmen used stamp forms with which they imprinted relief ornaments on the raw gesso, as can be seen in the fragment of the over-primed 18th-century background preserved by the restorers. on the icon of the Mother of God from the Deesis rank and the Great Martyr. Demetrius of Thessalonica in Uglich (XVI century, GGG: Avtonova, Mneva. Catalog. T. 2. P. 468–469. Cat. 990). Shotting of backgrounds also became widespread, when ornaments and patterns were embossed on gilded gesso, or ciphering was done - scratching ornaments with a needle on gilded ground. In some cases, when it comes to “replicating” specific, especially revered icons in frames, imitation frames have been encountered.

In the development of the personal, traditional techniques were generally preserved. However, highly professional craftsmen often turned to the selection technique, in which the faces and open parts of the body were made with the thinnest short strokes, not merging and sometimes crossing each other.

Folk artel icon painting was distinguished by its primitive execution, although one can note unique technical and professional techniques in it, aimed at quick execution and a certain iconic “readability” of the image. On a thinly laid ocher background, iconographic schemes were sketched with quick strokes, filled with single-color colorful spots, in which images popular in peasant everyday life are easily recognizable, for example, the Mother of God “The Burning Bush”, St. Nicholas the Wonderworker, patrons of livestock breeding. George, Saints Modest of Jerusalem and Blaise of Sebaste. Poor-quality topcoat varnish on such icons “turned red” over time, for which these icons received the name redneck. Many of them were covered with stamped brass frames. Along with the latter, handmade frames made from carved foil were used, the production of which was carried out mainly by women in Mstera and Kuban. Under them, according to a simplified scheme, only faces and hands, visible in the slots of the frames, were executed on the boards. Such icons were called “podkladniki”. The products of traveling artels were called “traditional” icons.

The image of the icon painting technique of this period is also complemented by some still little-studied features of a regional nature. In folk icon painting in the Urals (not to be confused with Nevyansk icons), colored varnishes were used. Kuban icons were distinguished by the originality of their execution. Their simplified interpretation is dominated by iconographic schemes of a Western nature, adapted to familiar Orthodox images (for example, the “Christ in the Press” icon). Written on thin small tablets in an academic manner, they were lavishly decorated with virtuoso decorative foil frames. Chemical analysis of the pigments and binders used has not yet been carried out.

Frequent violations of technical processes in icon painting, especially in the 19th century, led to a fairly rapid destruction of the soil and the paint layer of the icons. Therefore, there are cases of complete renewal of icons after a fairly short period of time from the moment of their execution - after 20–30 years.

MM. Krasilin

Lit.: “About the binder”: Manuscript of an unknown master, stored in Bern // Communication. VTsNILKR. M., 1961. No. 4. P. 196; Berger E. Beiträge zur Entwickelungsgeschichte der Maltechnik. Münch., 1912². Folge 3: Quellen und Technik. der Fresko-. Oel- und Tempera-Malerei der Mittelalters von der byzantinischen Zeit bis einschliesslish der “Erfindung der Oelmalerei” durch die Brübder Van Eyck. S. 18–19; Schmid G. Antique fresco and encaustic techniques. (M.) 1934. S. 112, 126; The materials and Techniques of Medieval Painting. NY, 1956. P. 55; Theophilus. De diversis artibus/Ed. and transl. CR Dobwell. Oxf; NY 1961; Slansky B. Painting technique. M., 1962, S. 337; Theophilus manuscript “note on various arts” // Communication. VTsNILKR.M., 1963. No. 7. pp. 66–194; Matxew G. Byzantine Aesthetics. L., 1963. P. 1, 29–30; Pertsev N.V. On some techniques for depicting a face in ancient Russian easel painting of the 12th-13th centuries. // Message Timing belt L., 1964. Issue. 8. pp. 89–92; Volkov N.N. Color in painting. M., 1965. S. 103–106, 110; Chatzidakis M. An Encaustic Icon of Christ at Sinai // The Art Bull. NY, 1967. Vol. 49. N 3. P. 197–208; Winfield DC Middle and Later Byzantine Wall Painting Methods // DOP. 1968. Vol. 22. P. 61–139; Birshtein V.Ya. Methods of analysis and the problem of identifying binders. // GBL: Information Center on Issues of Culture and Art. Overview information. M., 1975. S. 35–49; Weitzmann K. The Monastery of St. Catherine at Mount Sinai: The Icons. Princeton, 1967. Vol. 1. P. 18; Bykova G. Z. Restoration of the encaustic icon “Sergius and Bacchus” of the 6th-7th centuries. from the Kyiv Museum of Eastern and Western Art // Artistic heritage: Storage, research, restoration. M., 1977 Issue. 2 (32). pp. 124–134; she is the same. Research and restoration of the encaustic icon “Martyr and Martyr” // Ibid. pp. 104–111; Kitzinger E. Byzantine Art in the Making. L., 1977. P. 120; Birshtein V.Ya., Tulchinsky V.M. Identification of some materials of painting the icon “Martyr and Martyr” using the method of IR spectroscopy // Artistic Heritage. 1979. Vol. 5 (35). pp. 198–202; Popova O.S. Art of Novgorod and Moscow 1st half. XIV century M., 1980. S. 82–87; Muzeus L.A., Lukyanov B.B., Yakovleva A.I. The oldest pre-Mongol icon from the Moscow Kremlin museums. // Artistic heritage. 1981 Issue. 7 (37). P. 99; Yakovleva A.I. “Erminia” of Dionysius from Fourna and the technique of icons of Theophanes the Greek // DRI M., 1984. [Issue] XIV-XV centuries. pp. 7–25; she is the same. Origins and development of pictorial techniques of Russian monuments // DRI. M., 1993. [Issue:] Problems of attribution. pp. 54–71; she is the same. Icon technique // History of icon painting. VI-XX centuries Origins, traditions, modernity. M., 2002. S. 31–39; Golubev S.I. Painting technique in the artistic structure of the Byzantine icon // Material culture of the East: Collection. Art. M., 1988. Part 2, pp. 254–273.

A.I. Yakovleva

Subjects and symbolism of color

The icons depict:

- Christ;

- Mother of God;

- saints; Among them there are quite a few where scenes from the life of the saint of God are written in the margins around the “ark”.

- Angelov.

In addition, a special group of images are dedicated to holidays, especially significant events of the church year.

The colors used by icon painters have their own symbolism:

- white – the light of the Kingdom of Heaven (for example, on the icon of the Transfiguration);

- red – Deities;

- blue – earth; It is characteristic that Christ is written dressed in a red tunic, a blue himation (the Divinity clothed with Humanity), and the Mother of God - in a scarlet tunic and a blue tunic - that is, humanity is clothed with Divinity through the Incarnation of Christ;

- green – the color of life, nature; green himation - on an Angel, which, according to a number of interpretations, symbolizes the Holy Spirit on the icon of St. Trinity St. Andrey Rublev;

- finally. The underworld, Hell, is written in black.

Features of Orthodox icon painting

The most important of them can be considered reverse perspective, the basic principle of imagery. If in direct perspective it is similar to a photograph taken from one point, then in reverse perspective we, for example, can see:

- at least three planes of the table (and not one, if it were a painting), as in the image of the Holy Trinity by St. Andrey;

- part of the face turned in profile, which would not be visible in a portrait familiar to a modern person; hence the seemingly “disproportionate” faces on the icons of the Virgin Mary with Christ.

According to the famous culturologist B.A. Uspensky, this means that the master creating the icon is immersed in what is depicted and “lives” in it. But the researcher of Byzantine culture A.M. Lidov thinks a little differently: with reverse perspective, the image, in fact, is located between the plane of the board and the person - simply, next to him. This was especially acutely understood by Russian peasants, for whom it was customary to hang up icons if there was an intention to sin in some way, so as not to see accusatory glances.

Differences between icon painting and painting

Constituting a special branch of painting, icon painting, however, differs significantly from this art in the generally accepted sense of the word. Painting - whatever its direction, realistic or idealizing - is based on direct observation of nature, takes forms and colors from it and, providing, to a greater or lesser extent, scope for the artist’s creativity, involuntarily reflects his individuality; on the contrary, icon painting, without turning to nature for reference, strives only to unswervingly adhere to the principles sanctified by tradition, repeats long-established types of images that have received, so to speak, dogmatic significance, and even, with regard to technical techniques, remains faithful to the precepts of antiquity; the performer of such works, the icon painter (isographer), is a completely impersonal worker, stereotypically reproducing compositions and forms once and for all indicated to him and his brothers and, if he has the opportunity to show his skill in anything, then only in the thoroughness and subtlety of the work. Icon painting acquired such a character in Byzantium depending on the establishment by Orthodoxy of unshakable dogmas of faith and unchanging church rituals; from here it passed to Italy, where it was respected and imprinted on local art until the advent of the Renaissance; Having been transferred from Greece, together with Christianity, to our fatherland, it took root in it and to this day occupies many hands among us and enjoys preference among the masses over religious painting in the spirit of Western Europe. art schools. Leaving aside Byzantine icon painting itself, let's take a quick look at the history of this art in Russia.

Byzantine icon painting

It reaches a special peak after the VII Ecumenical Council, from the 9th century. In no more than 100 years, an iconographic canon is formed and the main subjects are developed. From the 12th century Iconic writing is gradually declining due to the political situation in the country. However, until the 16th century. famous icon painters of St. Mount Athos.

Angel Golden hair. Unknown icon painter. Second half of the 12th century Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

The art of icon painting of Ancient Rus' (Kievan Rus)

Of the masters of this time, the most famous is St. Alypiy, monk of the Kiev-Pechersk monastery . They said that the images he painted were considered miraculous. And the last icon, which one lover of God ordered for the saint, was not finished by the already ill master - it was completed by an Angel who appeared to him. One can only guess about how rich the iconography of Ancient Rus' was - most of these treasures were destroyed during the Mongol invasion.

Icon of the Mother of God of Pechersk-Svenskaya, Tretyakov Gallery.

brief history of icon painting

Iconography - (icon and write) - icon painting, theology in colors - a type of religious painting based on the Tradition of the Christian Church and the Holy Scriptures. Icon painting creates sacred images that are called upon to raise worshipers from image to prototype, hence the frequent name of the icon - image , in modern language, a projection of the spiritual world in the material.

Icon painting originated in apostolic times. In the first century after the Nativity of Christ, according to Church tradition, the first icon was painted by the Apostle Luke himself on a simple wooden tabletop. This image began to be called the image of the Vyshgorod, and then the Vladimir Icon of the Mother of God of Tenderness, so named after the transportation of the icon of St. Prince Andrei Bogolyubsky to Vladimir. From the first centuries of Christianity, even during persecution, Christians began to depict the foundations of their faith with symbols. Evidence of this is the paintings in the Roman catacombs that have survived to this day.

Icon painting survived the period of iconoclasm . For two centuries (from the 8th to the 9th), the persecution of holy images continued, which were declared idols, and the people who worshiped them idolaters. The result of iconoclasm was the barbaric destruction of icons, frescoes, mosaics, the destruction of painted altars in many Byzantine churches, and icon worshipers were persecuted and destroyed. The Council of Constantinople in 842 restored the veneration of icons and condemned iconoclasm . After the council, which condemned iconoclasm and restored icon veneration , a church celebration was held, which took place on the first Sunday of Lent. In memory of this event, on the first Sunday of Great Lent, the Church established a holiday for the restoration of icon veneration , called the “Triumph of Orthodoxy.”

Traditional icon painting in Russia was borrowed (like the entire structure and Rules of Divine Services) from Byzantium. The first teachers of icon painting were invited from there. Icon painting began in the 10th century and was marked by the Baptism of Russia. Icon painting was the leading church-based fine art in Russia until the 8th century, when it was gradually replaced by secular types of fine art. Icon painting schools appeared in various principalities. This conventional division into schools according to principalities was not without reason, because each school was characterized by an individual writing style. A distinctive feature of each icon painting school is iconographic design , i.e., in other words, the manner of applying the drawing to the board, the color scheme and the cutting of clothes. The classical school of icon painting has always been the school of the Moscow Principality, the founder of which can be considered Ave. Andrei Rublev, Dionysius with his sons, Daniil Cherny. The drawings of the Moscow school were distinguished by classical, strict and correct proportions of figures, faces and other elements of icon painting compositions , the influence of the Byzantine style, golden backgrounds, richly decorated clothes with gold, etc.

By the 18th century, icon painting began to undergo stylistic changes. A tendency towards greater realism emerged; behind the desire of icon painters to overcome iconographic conventions and subordinate compositions to realistic laws, the spiritual component of iconographic images began to slip away. The so-called parsuns appeared - an iconographic image of living people, the ancestors of the portrait.

Under Peter the Great, icon painting completely faded into the background. The Academy of Arts was founded. Artists went to study abroad. Art began the path of secularization. This trend was also visible in the spiritual life of society. In parallel with the acquisition of European values, Russia was losing its spiritual heritage - icon painting . A characteristic feature of that time was the appearance of realistic painting, civil buildings in the European style, the appearance of art styles dictated by Europe (rococo, baroque, classicism, romanticism, etc.), secular literature and poetry, and science. The emphasis was shifted from the spiritual to the secular, worldly. Hence the concept - secularization.

In subsequent centuries (XVIII and XIX centuries), icon painting was transformed into temple painting, which had nothing in common with ancient canons and traditions. The symbolic component has gone, realism and detail have appeared, distracting from spiritual and mystical contemplations, giving free rein to fantasies. Iconographic canons have gone into oblivion . Now “icons” are painted not by monks, not by initiated persons, but by simple artists, albeit eminent ones, but sometimes even with little church (Vrubel, Nesterov, Vasnetsov and others). They, of course, tried to understand, delve into, study the issues of icon painting of our ancestors, but traditions seemed to be irretrievably lost.

The 20th century gives us the name of Andrei Rublev. At the beginning of the century, Igor Emmanuilovich Grabar realized the lack of authentic works of Russian medieval painting. A whole layer of the history of fine art for many centuries was forgotten and lost. At this time, under the leadership of Grabar, the clearing and restoration of many monuments of fine art began. The result was the appearance in our world of many works of icon painting from the Middle Ages. The most significant discovery of the restorers of that time, who worked in the Moscow Kremlin, the Trinity-Sergius Lavra and Vladimir, was the clearing and discovery of icons by the 15th-century icon painter, monk Andrei Rublev.

The first quarter of the 20th century was characterized by the beginning of the revival of the ancient Russian art of icon painting !

Golden age

It is associated with the revival of the country in the 14th century, which it largely owes to the giants of the spirit - with W. Peter, Alexy of Moscow , Venerable. Sergius of Radonezh . At the same time, St. Peter himself was an icon painter, and St. The image of the Holy Trinity was dedicated to Sergius by St. Andrey Rublev . It was his work that largely determined the 14th century. as “golden” for Russian icon painters.

Iconography: Hospitality of Abraham (Old Testament Trinity) Dating: XV century. 1425–1427. Icon painting school or art center: Moscow school Icon painter: Andrey Rublev Origin: From the Trinity Cathedral of the Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius. Material: Wood, tempera. Dimensions of the icon: height 141.5 cm, width 114 cm The scene of the silent communication of three angels is brilliantly revealed by the icon painter in the gestures of their hands - the left angel (God the Father) blesses the sacrificial cup, the middle angel (God the Son) is ready to accept this cup, his hand with a symbolic the folds are lowered, the pose expresses filial submission to the will of the Father and the readiness to sacrifice oneself, the right angel (God the Holy Spirit), “finishing the conversation,” affirms the high meaning of sacrificial, all-forgiving love. Unlike many compositions of this iconography, only one bowl with the head of a calf is presented on the table; it becomes the semantic center of the work - a symbol of the New Testament sacrificial lamb. The silhouette of the chalice is rhythmically repeated in the lines of the inner contours of the left and right angels, forming a large Eucharistic chalice in which the central angel, Jesus Christ, is placed. Setting of the icon of the Holy Trinity, letter from Andrei Rublev. Inv. No. 13012. © State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow Literature: Iconography from the collection of the Tretyakov Gallery. M., 2008. pp. 114-115.

Old Russian icon painting

Along with architecture, icon painting also developed in Rus'. Being a work of painting, an icon, however, differs sharply from a secular painting. In the church view, the icon appeared as a connecting link between the believer and the deity. Therefore, the artists of ancient Russian painting adhered strictly to religious subjects, however, they still invested in them their ethical and aesthetic ideals, dreams and hopes.

The icon was painted on boards; sometimes canvas was glued onto the boards, primed, and covered with a layer of drying oil on top for durability. The artists used natural paints - plant and mineral, which were mixed with egg yolk and plant juice.

In 842, at the Ecumenical Council, a strict theological definition was given of “what an icon is” (in Greek, “icon” is a likeness, an image). Its essence is that the icons depict not a deity, which is incomprehensible and unknown, but his human image. “Human and object forms should be shown in the icon, although conditionally, but life-like, with the help of appropriate and decent colors.”

Intercession of the Virgin Mary (Novgorod Icon)

Features of Russian icon painting. Old Russian icons have an individual feature in the depiction of images and figures. Unlike the religious subjects of Italian and European artists, where the figures are depicted three-dimensionally, on Russian icons the figures are flat, ethereal, incorporeal, they seem to glide along the plane of the icons.

Icon painters used various symbols and techniques in their subjects, with the help of which they conveyed in icons the idea, dreams and aspirations of both their own and the Russian people. These symbols were understandable to the people, which is why the icons were so close and dear to them. What are these symbols? A star, for example, means deification. A winged youth blowing into the pipes is the wind. Women holding amphorae from which water flows - rivers, streams of water. Circle - eternity, eternal life. The maiden on the throne in a crown and robe - spring. People with crosses in their hands are martyrs. The wavy hair of angels, tied with ribbons, are rumors denoting higher vision, knowledge.

Color is also a kind of identifying mark of images: we recognize the Mother of God by the dark cherry cloak, by the light crimson cloak we recognize the Apostle Peter, and by the bright red background we recognize the Prophet Elijah. Colors are like the alphabet: red is the color of martyrs, but also the fire of faith; green - expression of youth, life; white is associated with the highest rank, it is the color of God. Gold color is also the color of God.

The ancient Russian masters lavished paints with such simple-minded childish generosity, which no adult artist would ever dare to do; apparently, this was supposed to correspond to the evangelical words: “Truly I say to you, unless you are converted and become like children, you will not enter the Kingdom Heavenly."

The background of the icon was traditionally covered with gold. Gold not only symbolized Divine light, but also created a flickering, mystical light that illuminated the icon with the flickering flame of a lamp and the image on it either appeared or moved beyond the line where mortals have no access.

Our ancestors treated holy images with great reverence: they were not sold, and old, “fading” icons could not simply be thrown away or burned - they were buried in the ground or floated on water. Icons were the first to be taken out of the house during a fire and were bought out of captivity for a lot of money. Icons were required both in a peasant hut and in a royal palace or noble estate. “Without God you can’t reach the threshold” - this is how this proverb reflected the real life of people of that time. Sometimes icons were declared miraculous, miraculous; military victories, the cessation of epidemics, and droughts were attributed to them. The icons are still treated with care; they exude joy, enjoyment of life, strength and purity.

Icon-painting art of the 17th century

From the 16th century secularization is growing: non-canonical icons appear like the “Trinity of the New Testament”, which depicts God the Father - contrary to the ban of the Hundred-Glav Council. By the 17th century Even worldly subjects and images begin to penetrate into icon painting. Some icon painters question the reverse perspective itself as a principle, insisting on the icon as a kind of “portrait”.

For example, the court icon painter Joseph Vladimirov writes that Christ on the Nativity icon “ is in every possible way appropriate to be white and rosy, especially molded, and not unsculpted, according to the prophet who says: The Lord reigns and is clothed in beauty! And again: Lord, in the light of Your face let us go... How gloomy and dark is it to write His face there?”

Guided by the spirit of the world, masters increasingly want to make the icon “beautiful” rather than spiritual; the works of former times seem “gloomy” to them.

In 1663, Simon Ushakov created one of his most famous works - the icon “Praise to the Vladimir Icon of the Mother of God,” or “Tree of the Russian State,” for the Trinity Church in Nikitniki. XVII century Icon painting school or art center: School of the Armory Chamber. Origin: from the Trinity Church in Nikitniki in Moscow. Material: wood, tempera. Dimensions of the icon: height 105 cm, width 62 cm. The first Moscow Metropolitan Peter and Prince Ivan Danilovich Kalita are depicted against the background of the Assumption Cathedral. They plant and water a tree, which seems to grow through the Assumption Cathedral, filling the entire surface of the icon with branches. On the branches of the tree there are medallions with images of Moscow saints, and in the central largest medallion there is an image of Our Lady of Vladimir. Behind the Kremlin wall are Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich and his first wife Maria Ilyinichna with their children. Above in the clouds is the Savior, presenting the soaring angels with a crown and chasuble for Alexei Mikhailovich: the king of heaven crowns the king of earth. The images of saints in medallions are arranged from bottom to top with some deviations from the historical sequence, as if in accordance with the “growth” of the tree. On the left branch, behind Metropolitan Peter, are the fathers of the Russian Church: Metropolitans Alexy, Cyprian, Jonah, Photius and Philip, Patriarchs Job and Philaret, Tsars Mikhail Fedorovich, Theodore Ioannovich, Tsarevich Dmitry. On the right branch in the first medallion is depicted the grandfather of Ivan Danilovich Kalita, Prince Alexander Nevsky, in the clothes of a schema-monk. Behind him are the founders and abbots of monasteries close to Moscow - St. Nikon of Radonezh, St. Sergius of Radonezh, St. Savva of Storozhevsk, St. Paphnutius of Borovsk, St. Simon the Silent, St. Andronik and the Moscow blessed Maxim, Vasily, John the Great Cap. Inv. No. 28598. © State Tretyakov Gallery,

On the relationship between language and style in Orthodox icon painting

| 1. Rafael Santi. Sistine Madonna. 1515–1519 |

For the first time in the philosophical discourse about the language of ancient Russian art, E.N. began to write in the second decade of the last century.

Trubetskoy[1]. A little later, priest Pavel Florensky spoke about the semantics of iconographic language in the famous treatise “Iconostasis”. L.F. devoted a good half of the book “The Language of Painting” to this problem. Zhegin[3], spiritually and intellectually connected with Father Pavel. In the last quarter of the 20th century, much attention was paid to the language of the icon of L.A. and B.A. Uspensky, B.V. Rauschenbach, A.A. Saltykov, I.K. Yazykov[4]. It was mainly art historians who thought about the iconographic style[5]. But few people directly addressed the issue of the relationship between language and style, which should have been done long ago due to pressing life circumstances. From the very beginning it is essential: what is the language and style of the icon? Where is the border between them and how to determine it? Unfortunately, iconologists have not spoken enough about this, and sometimes not quite as clearly as they would like. Let me give you a well-known quote from L.A. Uspensky, especially often found in articles by Orthodox authors: “The “style” of the icon was the property of the entire Christian world throughout 1000 years of its history, both in the East and in the West: there was no other “style”. And his entire path is only the disclosure and clarification of his artistic language or, on the contrary, its decline and retreat from it. Because this “style” itself and its purity are determined by Orthodoxy, a more or less holistic assimilation of revelation. And this language, naturally, is subject to changes, but changes within the iconic “style,” as we see throughout its almost 2000-year history”[6]. Several contradictions are noteworthy. First it is said that the style of the icon is “uniform and unchangeable,” but it has a language that is subject to change, and precisely within this single style. And here doubts arise. Omitting logical errors, it would probably be more correct to talk about the comparative immutability of the language within which the iconic style changes. If we resort to an analogy in literature, then the Old Russian language remained much more stable relative to the styles available in it. The language of worship is stable, therefore Church Slavonic and Latin remain liturgical and not colloquial languages, i.e. virtually unchanged (in any case, the development of the Church Slavonic language took place within its own system, and not due to the influence of other systems; now, however, they are trying to impose such influence on it). M.V. Lomonosov exclaimed: “It’s not like languages suddenly change! It’s not like that all the time!”[7]. It’s unclear in L.A. Uspensky and more: if the “style” of the icon was the property of the entire Christian world for 1000 years of its history, then how was the language subject to changes within this style “for almost 2000 years of its history”?

And yet, style is often synonymous with language, and vice versa, the word “language” is understood as style. In this case, the boundaries between them are not easy to determine, because the edges are quite blurred. The literary expressions “language of the master” and “folk language” are evidence of this. It follows that we need to dwell at least briefly on the specific features of style and language. By style we usually mean the commonality of a figurative system, means of artistic expression, and certain techniques characteristic of an artist, school, or era. And language is a means of interpersonal communication, as well as of nations and peoples[8]. Language, to a certain extent, is even a “tool of thinking.” How applicable will such an understanding be to icon painting? Is it more correct to attribute the so-called “lifelikeness” to style or to language? When the icon became “life-like,” did the style or language change?

| 2. Hieromonk Alipius (Konstantinov). Valaam Icon of the Mother of God. 1878 |

To answer similar and related questions, given the many formulations of the concepts under consideration, we need to agree on the stability of some definitions.

Therefore, we propose to consider as a style such a unity of the way of thinking (Christian) and the way of displaying the world (spiritual), when thinking and display are in an inextricable, harmonious connection. The more complete the artist is as a person, the more perfect the style becomes. The ancient Russian hesychast icon painters were especially distinguished by their unity and connection in style. The Jesus Prayer directed the thinking of grief, and the Holy Spirit gave the ability to see and find means of displaying the heavenly. This can be regarded as the true Christian worldview captured on the icon. Hence, some researchers quite rightly consider style to be organically related to worldview. N.M. Tarabukin wrote, for example: “Style is a historical and therefore relative concept. Art in its historical development goes through a complex stylistic evolution, which is quite natural, since art itself is part of culture as a whole. The change of styles is due to a change in worldviews, because style is a formal expression of a worldview. The worldview in icon painting – like the worldview of Christianity – is united”[9]. A.F. spoke about style in a similar way. Losev, D.S. Likhachev, G.A. Gukovsky and others. And again the question invariably arises: should icon painting include its language as a worldview? The answers may vary. M.V. Vasina offers her own version: “In relation to the iconographer, it is more correct to pose the question not so much about worldview, but about faith - about faith in the One Whom the icon painter depicts and in the light of Whom the otherworldly principle becomes clear in the world. So we certainly move on to the language of the icon in which it speaks. Her language is canon. And style is the character of the image”[10]. But does faith exist without a worldview? Vasina, contrary to explanatory dictionaries, unfortunately identifies worldview with ideology, contrasting, oddly enough, Tradition with worldview: “It is to Tradition that the icon belongs as an image that does not come from representation (or vision), but transmitted and living in the environment of Church Tradition, but not a worldview.”

Firstly, we should immediately clarify: we do not tear the icon away from Tradition and do not put the worldview ahead of it - to the same extent that Christianity cannot be primary than Christ Himself. Secondly, would the further life of Tradition be possible without the structure of thinking that the Church requires of a Christian and which is textbook called worldview? Thirdly, let us emphasize the difference: representation is one thing, and worldview is another; It is not always possible to put a sign of identity between them. In the 8th–9th centuries, during times of opposition to iconoclasm, cult visual art very eloquently confirmed the fact that it is a visible expression of faith. And this - in the absence of the named identity - is a direct indication of a worldview. Nevertheless, we agree with the researcher: it is quite reasonable to consider the canon the language of icon painting. Consequently, the language of icon painting inevitably includes ideological aspects, for if language is a means of depicting a prototype, then, of course, it cannot be non-Orthodox[11]. With an Orthodox worldview, without knowing any doubts, M.V. Vasina, connect the canon of S.S. Averintsev[12] and V.V. Lepakhin[13].

With this understanding of the language of art, it becomes clear that “lifelikeness” refers to both style and language, because “lifelike” icons clearly cannot be called canonical, and the means of depicting the prototype are too reminiscent of Catholic ones. Indeed, in icon painting, language and style are mutually determined by the Orthodox worldview: if the language is distorted, then corresponding consequences for the style will inevitably occur, and vice versa, if something alien to the Orthodox worldview is introduced into the style, then distortions of the language cannot be avoided. The stability of the language that L.A. What Uspensky meant by the expression “style” of the icon is explained by the stability of the Orthodox worldview. The way of thinking remained Christian, but the ways of displaying the world were refined and then began to evolve. And even this evolution began to affect the way of thinking over time. Consequently, ideological changes occur both in style and in language; more specifically - religious, doctrinal. This is not surprising. “Fryazhskaya” and later academic icon painting appear under the influence of Western trends, which, of course, was an expression of a new paradigm of consciousness. The only question is how new the paradigm was. The attitude towards the icon remained Orthodox, but the understanding of icon painting, in view of the separation of theology from patristic tradition, began to more closely correspond to the spirit of the Enlightenment, i.e. secularization penetrated into the understanding of the church image. If “they still prayed in Slavic, but theologized in Latin” (Archpriest Georgy Florovsky), then this could not but affect their understanding of the world. The clergy, “with their church consciousness crippled by scholasticism, as well as the enlightened person of this era, became closer and more understandable to the “Christian” image in its Roman Catholic guise than to the Orthodox icon. And it’s not that the icon became alien to them; but its Orthodox content was gradually and persistently erased from consciousness. Therefore, the dominance of Western art forms took place, if not always with the assistance, then, in any case, almost always with the passive attitude of the clergy, but with the active intervention of the authorities,” noted L.A. Uspensky[14].

| 3. The Virgin and Child. Byzantium. VI century. The icon was painted in the pre-iconoclastic era |

However, if an icon is not canonical, then can it be considered an icon?