Childhood, education and first steps towards God

The future archpastor was born in 1651 near Kiev into a Cossack family. Both the father and mother of the child led a pious and God-fearing life, so little Daniel (as the saint was called in the world) grew up in an atmosphere of love and faith in God. It is noteworthy that in his diary entries, the son describes with great reverence the quiet and peaceful death of his mother. From this entry it is clear that the son loved his mother very much and considered her life an example of faith.

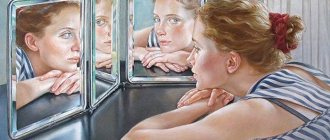

Saint Dmitry of Rostov

Daniil received his first education at home, his parents themselves taught him to read. When he grew up and the time came to study further, he entered the school, where he quickly became one of the best students. He was especially good at the art of rhetoric and public speaking. The skills acquired during his studies helped the future great preacher develop a unique style of speech, which gave his words and sermons special persuasiveness, fervor and sincerity.

A distinctive feature of the young man already in the years of his apprenticeship was a deep spiritual contemplative life. He was alien to the usual amusements for young people; in his free time he prayed, read the Bible and the holy fathers. He loved the temple of God very much and tried not to miss services.

Unfortunately, the political situation in the country did not allow the gifted young man to complete his studies. Ukraine at that time was constantly coming under the authority of different states, and military conflicts were constant. The school where the future ascetic studied was destroyed, and the students had to interrupt their studies. But even those three years spent at the school were enough for the young ascetic to learn a lot and finally become confirmed in his choice to take the path of monasticism.

tonsure and abbess

While still a very young man, Daniel decides to go to a monastery. The parents did not create any obstacles in this choice of their son and gave their blessing, because they saw that this was exactly the path prepared by the Lord for their child. And the young man Daniel leaves home for the Kirillov Monastery. The rector of the monastery is the former rector of the school where Daniil studied, so the young man is greeted warmly at the monastery.

Saint Demetrius of Rostov

And then, in 1668, the most long-awaited event in Daniel’s life came—he was tonsured. The father abbot himself performed it, and named the new monk Demetrius. The newly minted monk immediately began to zealously fulfill the monastic rule, choosing Saints Anthony and Theodosius, as well as the rest of the Pechersk ascetics, as his example.

Important! Even as a monk, Father Dimitri did not abandon his studies and scientific research in his cell.

7 years after the first tonsure, Father Dmitry met with the then Metropolitan of Chernigov. Seeing that before him was a talented and zealous servant of the Lord, the bishop invited the monk to preach in the Chernigov diocese. There he quickly earned the love of ordinary people and church ministers. Many monasteries and large parishes began to invite Father Dmitry to listen to his edifying sermons. The power of his word was such that many people believed in the Lord.

Having visited a large number of monasteries and met many church hierarchs, Father Dimitri receives an invitation from the brethren of the Kirillov Monastery to become their abbot. The archbishop without hesitation approves the inspired monk, and Father Dimitri becomes abbot.

Subsequently, by the Providence of God, he will head more than one monastery, and in every place Saint Dmitry will be an example for all the brethren. A strict ascetic life, asceticism, and at the same time a lively participation in the life of every person made him a favorite abbot in every monastery.

About Orthodox monasteries:

- Mother of God Assumption Monastery in Tikhvin

- Joseph-Volotsky Monastery in Moscow

- Zadonsky Tikhonovsky Transfiguration Monastery in the Lipetsk region

Lives of the Saints. Dimitry Rostovsky

Peace to you, dear visitors of the Orthodox website “Family and Faith”!

On November 10, the memory of St. Demetrius of Rostov is celebrated. Many of us know his name thanks to his books with the lives of saints for every day of the year.

Lives of the Saints

Let's find ourselves visiting some 18th century landowner.

The old maid will cook for us a side of lamb with buckwheat porridge and jelly. And the good landowner will entertain you with stories from his life until the evening. And before going to bed, he will pull back the curtain covering the bookshelves and show his main treasure: four huge volumes in leather bindings. On these autumn days, he will certainly pull out the third volume, on which is written “September, October, November,” open its wide yellowed pages and begin to read the ancient, majestic stories about the ancient saints and martyrs. After all, these books are the lives of saints for every day of the year, which were written at the turn of the 17th and 18th centuries by St. Demetrius of Rostov. He began his work within the walls of the same Kiev-Pechersk monastery, in which the Russian written word was born six centuries earlier, and finished in the north, in Rostov the Great, where he was appointed bishop. The saint wrote these four volumes for twenty years, and, in the end, he himself became a saint. Now among the lives of the saints there is certainly the life of St. Demetrius of Rostov. Whom a person writes about is who he can become like. So it’s joyful and useful to write and read about the saints!

For many years, the lives of the saints were the most beloved and almost the only reading of our ancestors.

But then different novels and stories began to appear. And already in the 19th century they replaced the lives of saints. The further, the less people began to read about the saints and martyrs, and more about their contemporaries, people just like them, passionate, sinful and restless people.

Saint Demetrius of Rostov

Daniel, that was the name of Saint Demetrius before monasticism, was born in Makariev, near Kyiv, in December 1651 into a pious, believing family. From an early age, Daniel was taught respect for God's law, devotion to the Church and the Fatherland.

Daniel completed his education at the Kiev fraternal school. During his studies, the boy more than once aroused admiration from teachers and administration due to his innate abilities, diligence and determination.

Along with theoretical disciplines, Daniel sought to absorb practical skills of life in Christ. He preferred church services and reading spiritual literature to noisy student groups.

In 1665, the Polish conquerors set fire to the school, and Daniil was forced to return to his parents' house. At home, he did not abandon his studies, but with even greater spiritual impulse he devoted himself to self-education.

He often attended divine services, listened to the words of spiritual shepherds and teachers. Gradually his mind and heart inclined towards monasticism.

Monastic life

At the age of 18, Daniel was confirmed in his decision to take monastic vows. Having asked for the blessing of his parents, he went to the Kyiv St. Cyril Monastery. And in 1668, after some time of novitiate, Daniel took monastic vows with the name Demetrius.

In 1675, Demetrius was elevated to the rank of hieromonk. For some time he preached at the see of Archbishop Lazar (Baranovich). At the invitation of the Belarusian Bishop Theodosius, he carried out preaching activities at the Brotherhood of the Transfiguration Monastery for about a year. In 1681 he was appointed abbot of the Maksakov Monastery. A year later he was appointed head of the Baturin Krutitsa monastery. He ruled this monastery for a little less than a year, but then his heart demanded prayerful solitude. And he retired.

After some time, the rector of the Kiev-Pechersk monastery, Archimandrite Varlaam, invited Hieromonk Demetrius to the Lavra, so that he would carry out a responsible task that he had long planned: compiling the Lives of the Saints. In 1684, Saint Demetrius began this work.

Saint's works

By God's providence, Saint Demetrius was appointed to the Rostov See and from March 1702 he headed it. Getting acquainted with the state of affairs in the diocese, the saint came to the conclusion that the Church needs to create educational institutions to train future priests. At his own expense, he organized a school. This school was located near his chambers. It included three educational classes. The Bishop vigilantly monitored how the educational process was carried out. At the same time, he monitored the moral education of his students: he demanded that they regularly attend temple services, he himself performed solemn services, and he himself instructed them by word and example.

The great contribution of Saint Demetrius is revealed in his work to overcome schisms and fought against obscurantism and popular superstitions.

Around 1705, Saint Demetrius completed his work on the Lives of the Saints. During this same period of time, his health deteriorated significantly.

The faithful servant of Christ died in 1709, on October 28. He was found in his cell kneeling in front of the icons, but already lifeless.

Saint Demetrius, Metropolitan of Rostov

Cheti-Minea - the main work of St. Demetrius

For a long time, Archimandrite Varlaam of the Kiev Pechersk Lavra was looking for a monk capable of performing a large and complex task - collecting together all the known lives of the saints. During Polish raids and military conflicts, many liturgical and church books were lost, including the lives available at that time. The choice of archpastor to carry out this, without exaggeration, historical task fell on Father Demetrius, who at that time relieved himself of the duties of abbot and lived as a simple monk in one of the monasteries.

Dimitry Rostovsky

Interesting! Out of his great humility, the ascetic at first refused such responsible obedience for a long time, but later agreed, understanding the necessity of such work for the Church of Christ.

The saint of God worked in the Lavra for more than two years, compiling the lives of the saints. But the brethren of the Baturinsky monastery turned to him again, persuading him to take over control. The monk refused for a long time, citing his obedience, but in the end he gave in. So he again became abbot, but did not leave his work. Already in his new position, Dimitri finished and handed over to Archimandrite Varlaam his work, compiled for the months from September to November. The archimandrite highly appreciated the work of the abbot, and the first quarter of the Chetya-Minea was immediately put into print.

The first published book was highly approved by the church leadership, and Father Dimitri was awarded a patriarchal letter of commendation for his work. After this, he decides to devote his time entirely to writing the second book, and again relieves himself of his duties as abbot.

However, no matter how much the monk strived for a reclusive life, too many hearts needed his pastoral experience and Christian word. And the future saint becomes the abbot of the Peter and Paul Monastery. There, skillfully managing the monastery, he wrote the second part of the collection of lives of saints. After this, several more new appointments to other monasteries follow, and everywhere the ascetic does not abandon his work. The ascetic finishes the third part of the work with promotion in the hierarchy to the rank of Archimandrite of Chernigov.

Saint Demetrius of Rostov and his works

Saint Demetrius of Rostov

A significant role in the process of church and cultural construction in Russia at the turn of the 17th–18th centuries was played by immigrants from Ukraine and from Kyiv academic circles. Perhaps the most outstanding scientific monk among them should be recognized as Saint Demetrius of Rostov (Tuptalo; 1651–1709) - a wise theologian and an excellent preacher, a true unmercenary intellectual, the actual founder of Russian historical science and, no less important, the humblest monk and kindest shepherd [1].

He was born in the town of Makarov - relatively close to Kyiv, in the family of a Cossack centurion; his worldly name was Daniel. In Kyiv, the future saint took a course in theological sciences and studied foreign languages at the “collegiate” Epiphany Monastery, where “he appeared quite skilled in poetry and oratory and knew well everything that we teach”[2]. In 1668, he became a monk with the name Demetrius in the Kiev Trinity Cyril Monastery, not caring “about acquiring estates and temporary wealth”[3]. In 1675, he was ordained a hieromonk and appointed preacher at the then famous Gustyn monastery; At the same time he became the main preacher of the cathedral church in Chernigov. With great success, he then preached for some time in Lithuania - in Vilna (at the Holy Spirit Monastery) and in Slutsk.

Upon returning to Little Russia, Dimitri lived in Baturin, where from 1682 he served as abbot at the Nikolaev monastery. But less than two years had passed before he, “loving a silent and serene life and wanting to please God in private”[4], left his abbot duties, settling in the Kiev-Pechersk Lavra. Here, the council of elders of the monastery, headed by Archimandrite Varlaam Yasinsky (the future Metropolitan of Kyiv), instructed Demetrius to “collect the lives of the saints and, having completely corrected them, write them down”[5].

Chety Menaion of St. Dimitri for December. Con. XVII century (RNB. FI 651. L. 19)

In June 1684, the talented and hardworking monk began this feat of his entire subsequent life: compiling the history of the saints, or a corpus of historical hagiographic stories, arranged by month (in accordance with the annual circle of church “memories” of the glorified saints of the Ecumenical Orthodox Church), the so-called “ Chetyih-Miney." The first of four volumes went out of print in January 1689. At this time, Demetrius again served as abbot - in the already mentioned Baturin Nikolaevsky Monastery.

Soon the “clearly noble Hetman” set off from Baturin to Moscow, taking abbot Dimitry into his embassy. In the Trinity-Sergius Monastery near Moscow, Demetrius met Tsar Peter I, who, apparently, already then drew attention to the capable and educated Ukrainian monk.

When he returned to Little Russia, he was appointed abbot of the Peter and Paul Monastery in Glukhov; At the same time, in 1695, the second volume of “Chetikh-Menya” was published. Since 1697, Dimitri has already been the archimandrite of the Yelets Chernigov monastery, and since 1699 - the archimandrite of the Spassky Monastery in Novgorod-Seversky. Despite all these frequent movements of him from place to place by church authorities, the monk writer did not abandon the usual course of his literary works, and in 1700 the third volume of “Lives” was published.

As a result, “his special art in preaching the word of God, as well as his virtuous life, soon became known to the perspicacious monarch (that is, Peter I. - D.G.M.)” [6], and by Imperial Decree Demetrius was transferred to Moscow, appointing metropolitan of Tobolsk and Siberia. But for a sickly and already middle-aged southern monk, such an appointment to distant, cold Siberia was an unbearable burden, and most importantly, there, far from libraries and printing houses, completing his literary and historical work became almost impossible. Because of all this, the saint fell into “some sadness,” and only after finally explaining himself to Peter I did Demetrius receive permission to remain in Central Russia. In 1702, he was appointed ruling bishop to the Rostov-Yaroslavl department; He remained Metropolitan of Rostov until his death.

This saint was one of the most educated people of his time, a student and friend of Ukrainian spiritual educators - Lazar Baranovich and Varlaam Yasinsky, who invariably supported his literary work. In the “life” of Demetrius, compiled around the middle of the 18th century (in connection with his church canonization in 1757), it is especially emphasized that “this God-fearing man was of keen intelligence, great enlightenment, skilled in Slavic, Greek, Latin, Hebrew and Polish languages, had a great penchant for science”[7].

While living in Rostov, Saint Demetrius opened there the first theological seminary in Moscow Rus', gathering more than 200 children of clergy to study there; “for better order and success” he “divided them into three schools... often visiting these schools, he himself listened to the students and tried them in success”, “he himself worked in his free hours from church affairs, teaching them”, “he himself confessed them and the Holy Mysteries introduced; teaching, he assigned them to places, destroying ignorance”[8]. Moreover, Dimitri maintained these seminary schools with his own, generally very modest, funds.

Here, with the support of the then Patriarch Adrian (he served as a priest from 1690 to 1700), Demetrius completed his main 20-year work - “Cheti-Minea”, which is still used by all Orthodox Russia as the most complete and accurate source of church hagiography (detailed descriptions of the lives of saints).

In addition to theological works and various commentaries on the patristic writings, the saint also composed dialogues of an ethical nature, conducted polemics with the Old Believers (“Search for the schismatic Bryn faith”), wrote poetry and even the first Russian plays on evangelical themes. He also compiled two chronicles: “On the Slavic People” and “On the Appointment of Bishops.”

"Cell Chronicler" of St. Dimitri. Manuscript beginning XVIII century (RNB. Tit. No. 957. L. 1. vol. - 2)

Another of his “Chronicles”, “From the Beginning of the World to the Nativity of Christ,” was very important for that time. It was especially necessary, since few people could then purchase an expensive Bible for cell or home reading, and sometimes even representatives of the clergy did not really know the order of biblical events. Unfortunately, this work remained unfinished: the saint, as his biographer writes, this book “was not possible to complete due to frequent ailments: but only according to the calendar of the fourth thousand and six hundred years (that is, until 4600 from the creation of the world, or until 908). BC - D. G.M.) the acts were written”[9].

Among the most famous works of Demetrius, one should also name: “The Spiritual Alphabet” (teachings and admonitions for fulfilling the commandments of the Lord, arranged in alphabetical order), published in the Kiev-Pechersk Lavra after the death of the saint; then - “Irrigated Fleece” (about the veneration of the Mother of God and Her icons); “Apology” (“Conversation between a comforter and a mourner”) and “Short Catechism” (“very useful with questions and answers about faith”)[10].

Judging by the surviving portraits, Vladyka Dimitri was short, blond, gray-haired, with a small wedge beard, hunched over.

He, as a very kind and sincere person, was always concerned about human evil and social injustice. In one of his sermons he said:

“When the rich are eaten, the labors of the poor are eaten. And when he drinks, he drinks human blood, he drinks in human tears. Who is honored? - rich! Who is dishonest? - poor! Who is noble? - rich! Who is thin? - poor! Who is wise? - rich! Who's stupid? - poor! A rich man, even if he were very stupid, still makes the same thing, as if he is rich, smart among the common people.”[11].

Despite his holy rank, Demetrius sometimes had to endure a lot of oppression in Rostov from representatives of secular authorities. To his friend, Saint Stephen Yavorsky of Ryazan (1658–1722), this true spiritual citizen of Holy Rus' wrote about its “internal opponents”: “Too many iniquities, too many insults, so much oppression cry out to heaven and arouse the wrath and vengeance of God.”[12] The steward Voeikov, sent to Rostov from the state “monastery order”, was especially disrespectful to Saint Demetrius. Once the saint was serving the Liturgy in the cathedral, and at that time, by order of the steward, someone was punished with a whip “on the right.” The saint ordered that the torture be stopped immediately, but the royal official rudely refused the messenger. Then the saint, indignant in spirit, interrupted the service and went to his suburban village of Demyany.

Shortly before his death, Demetrius sent a family icon to the Kiev Trinity Cyril Monastery to be placed over his father’s coffin, and then wrote the following spiritual will:

“From my youth until I approached the grave, I did not acquire any property except the books of saints. He didn’t collect much from his cell income in the bishopric, not even a lot. But the other is for my needs, and the other is for the needs of the needy. I believe that it will be more pleasing to God, if not a single coin (coin - D. G.M.) remains for me, as if many were distributed in the collection. If no one wants to give me such a beggar the usual burial, then let them throw me into a wretched house (that is, as they said in the old days, “at God’s house” - into a common unknown grave. - D. G.M.). If, according to custom, they bury him, let him bury him in the corner of the church of the monastery of St. Jacob, where the place is for the signs. If you deign to remember my sinful soul without money in your prayers for God’s sake, let him himself be remembered in the Kingdom of Heaven. Demand a bribe for the remembrance, I pray, that the poor will not remember me, having left nothing for the remembrance. May God be merciful to everyone, and to me a sinner forever, amen.”[13]

St. Dimitry Rostovsky. Portrait of a parsun. Beginning XVIII century (?) (MPI)

A fairly detailed description of the blessed death of the saint has been preserved. On the last evening of his life, Vladyka ordered the singers to be called and, sitting by the heated stove, listened to the singing of the cants he himself composed: “My most beloved Jesus, I place my hope in God, You are my God Jesus, You are my joy.” Then he released everyone, detaining only his favorite singer, his closest assistant in his works and copyist of his works, Savva Yakovlev. He began to tell him about his youth, his years of study, about life in Ukraine, about monastic life and prayer, adding: “And you, children, pray the same way.” At the end of the conversation, the saint said: “It’s time for you, child, to leave for your home.” Having blessed the young man, the bishop bowed to him almost to the ground, thanking him for his help in copying his works. He became embarrassed and cried, and the saint meekly repeated once again: “I thank you, child.” The singer left, becoming the last person to see the saint alive. The Metropolitan retired to a special cell where he usually prayed. There, the next morning, October 28 (Old Style), 1709, the saint was found lifeless: he died during prayer, kneeling.

The burial service for Demetrius of Rostov was performed by his friend, Metropolitan Stefan Yavorsky, who promised him this.

The saint was buried in his beloved Rostov Spaso-Yakovlevsky Monastery, which was significantly rebuilt in the 18th–19th centuries, but to this day remains one of the most fertile corners of ancient Rostov-Yaroslavl; here and now the holy relics of this outstanding hierarch of the Russian Orthodox Church rest. They were found incorrupt in 1752, and soon the all-Russian canonization of the saint took place.

In the epitaph on the silver shrine with the relics, compiled at the same time by M. Lomonosov, the following words were placed, in particular: “Having written the lives of the saints, he himself was honored to be inscribed in their ranks in the summer of 1754, April 9th.” And below are Lomonosov’s poems in a somewhat ponderous and sublime edifying style, characteristic of that era, but, perhaps, have not lost their vital relevance in our time:

Oh you! that the Divine is honored within the close limits, His likeness should be in the bodily parts! Focus on what this saint taught, What now says to you from the faces of the powers above: Incline to the mercy of the Most High, to the truth, And you will be reconciled to your mother, the Church.

Cap, scarf, staff and diploma of St. Demetrius of Rostov. Spaso-Yakovlevsky Monastery. Photo: S.M. Prokudin-Gorsky, 1911

Metropolitan Dimitri left behind the richest collection of books for that time (about 300 volumes), which later passed to the Moscow Synodal Library.

As one of our church writers noted about the remarkable Rostov ruler, in the age of Peter’s “reforms” that came then, sometimes deeply anti-national and anti-church, this great man showed how one can be the most enlightened and progressive figure, without betraying the past of his people and remaining unconditionally faithful to the Orthodox Russian mood"[14].

Ordination to the rank of Metropolitan of Rostov

During the work on Chetii-Minea, Emperor Peter the Great himself became concerned about finding a primate to lead large areas of Siberia. At the direction of the Kyiv Metropolitan, the choice fell on Dmitry. However, he was so burdened by the prospect of moving to such remote villages, where he would not have access to the information he needed on the lives of the saints, that the ascetic fell ill. Having learned about this, Emperor Peter allowed him to wait for an appointment to a not so distant land. And after a short time, the ascetic was ordained Metropolitan of Rostov.

Ordination to Metropolitan

Having taken upon himself the work of leading the new metropolis, the ascetic discovered many problems and disturbances. Being a zealous servant of the Lord and his Church, he immediately began to eradicate all evil customs that had taken root in each parish. The primate was especially saddened by the attitude of the local clergy towards divine services and church shrines.

Important! In order to guide careless pastors on the true path, the new metropolitan issued two messages to the local clergy.

The first message was in the spirit of fatherly love and care, in it Saint Demetrius tearfully asked the shepherds to remember their status and their holy responsibilities towards their flock. The second letter was written based on the episcopal authority, which the Metropolitan commanded to give due respect and reverence to all church shrines, especially the Body and Blood of Christ.

Whatever power the metropolitan was endowed with, he understood perfectly well that it was possible to eradicate the spiritual vices of the local careless clergy only through a worthy example, exhortation and enlightenment. Therefore, at his home, he organized a parish school, where there were three classes with separate teachers.

At the school, the Law of God was studied, the Gospel was studied, and prayers were read regularly. Metropolitan Demetrius personally monitored the level of training of the students, and upon graduation from the school he assigned them to serve in churches, showing sincere concern for each of them.

Surprisingly, even with such a busy ministry, the ascetic had enough time and energy to continue working on the collection of lives of saints. So, already in the rank of Metropolitan of Rostov, he finishes and submits for printing the last fourth book of the Chetya-Minea.

Important! Thus, without interrupting his devoted service, Metropolitan Dimitri of Rostov completes the most complete collection of the lives of saints, the Chetya-Minea, historical for the Church. This work took him more than 20 years of his ascetic life.

Olga Lashkova Saint Dmitry of Rostov and the Chetyi-Minea

The article was published in the newspaper “History”. No. 11, 2007

From the first centuries of Christianity, events from the lives of saints that amazed and delighted their contemporaries were carefully memorized and recorded. Later, stories about saints began to be collected in collections, arranged according to the days of their memory.

This is the kind of work the person in question was doing. He worked for many years, collecting the lives of saints from a variety of sources, including foreign ones, translating them into Russian, editing them, collecting them for reading by month in collections called Chetii-Minea (Minea - month in Greek). Our story is dedicated to St. Dmitry, Metropolitan of Rostov, the most educated man of his time.

Daniel (this is the worldly name of Dmitry) was born in 1651 in Ukraine, in the small town of Makarov, 40 versts from Kyiv. His parents were simple people, from the Cossacks. However, Daniel's father, Savva Grigorievich Tuptalo, rose to the rank of centurion and subsequently received a noble rank. About the mother, only her name is known - Maria.

In those days, there was a fierce struggle for Ukraine (or Little Russia, as it was then called) between Poland, Russia and Turkey. As you know, in 1654, the part of Ukraine located on the left bank of the Dnieper was reunited with Russia. But the war continued, then dying down, then flaring up again, for right-bank Ukraine.

Savva Grigorievich’s family soon moved to Kyiv. The centurion left military service. He became a ktitor (manager) of the Kyiv Cyril Monastery.

Daniil began to learn to read and write at his parents' house, and he showed excellent abilities. In those years, the famous Brotherhood School, founded by the Ukrainian Metropolitan Peter Mohyla, was located in Kyiv. Daniel entered this theological school. And here the mentors drew attention to the excellent abilities of the teenager; they were also attracted by his modesty and unostentatious piety. Daniil eschewed amusements; his main hobby was study itself.

In his senior years, the young man studied poetry and rhetoric. He mastered techniques and figures of speech, which he later used in his writings and sermons.

Daniil, however, studied at school only until he was 18 years old. Kyiv was captured by the Poles, and the theological school was closed. For many years it remained desolate. (Subsequently, the school, or college, as it was called, was transformed into the Kyiv Theological Academy.) And the young man, following the inclination of his heart, three years later entered the Kirillov Monastery, where his father served as a ktitor. The abbot of the monastery knew Daniel well; he was the former rector of the Brotherhood School, Meletiy Dzik, known for his scholarship.

Here, in 1668, Daniel took monastic vows with the name Demetrius (in honor of St. Demetrius of Thessaloniki) and began to lead an ascetic lifestyle, so consistent with his nature. Soon Dmitry was ordained a hierodeacon. He remained in this ministry for about 6 years. Archbishop Lazar Baranovich of Chernigov, a learned man who enjoyed special respect in Ukraine, learned about the excellent abilities of Father Dmitry. He called a young deacon to him in Chernigov and ordained him as a hieromonk. So 25-year-old Father Dmitry became a priest and preacher at the cathedral. Being next to Bishop Lazar, he had the fortunate opportunity to deepen and expand his education.

Father Dmitry's bright, energetic sermons attracted people, and soon his name became known not only in Ukraine, but in Lithuania and Poland. Various monasteries invited Father Dmitry to their place; monks and laity wanted to hear his inspired word.

Father Dmitry began wandering around monasteries, visited Lithuania, and preached for a year in Slutsk. However, both Kyiv and Chernigov called him back. Great was the universal love for him...

Hetman of Ukraine Samoilovich, having heard about the wonderful preacher, invited him to his place in Baturyn. In the end, Father Dmitry moved to this city, preferring it to Kyiv, which was under threat of invasion by the Turks. The entire Trans-Dnieper Ukraine groaned from their devastation.

The hetman indicated the St. Nicholas Monastery near Baturin to Father Dmitry for residence. From here the young hieromonk continued his trips to the monasteries.

Soon Father Dmitry became abbot of the monastery. Some time passed, and he felt that this position distracted him from his academic studies. He resigned as abbot, but remained in the monastery. However, Father Dmitry had a presentiment that he would have to change his place of residence more than once. “God knows where I am destined to lay my head,” he once wrote in the diary he kept constantly.

Soon he was invited to move to the Kiev Pechersk Lavra to compile collections of the lives of saints. It must be said that by this time there already existed Chetya-Minea, books for reading, consisting of the lives of saints. However, all this required a lot of work to clarify, supplement, and new translations of texts. In addition, the ancient patericons (collections containing both the lives and moral sayings of the holy fathers) had to be presented in a language accessible to contemporaries. It was work that required patience, theological knowledge, and literary gift.

Appreciating the scholarship and abilities of Father Dmitry, the Kiev-Pechersk abbot Innocent Gisel entrusted him with this work. Father Dmitry in 1684 began to describe the lives of the saints.

This became his constant occupation, which he continued in the monastic cell, and in the rank of abbot, and becoming a bishop - and so on until the end of his life.

Father Dmitry worked with great enthusiasm in the Lavra, spending days and nights on manuscripts, sometimes he went to bed an hour before Matins. However, he was soon again appointed abbot of the Nikolaev Baturinsky Monastery. This appointment was approved by the new Kiev Metropolitan Gideon, who came from a noble family of princes Svyatopolk-Chetvertinsky. Bishop Gideon was appointed by the Moscow Patriarchate, to which the Kiev See was then subordinate. All this had huge consequences for Dmitry's father. As an experienced theologian, he took an active part in solving complex theological issues, and people learned about him in Moscow.

Correspondence began regarding Menaion with the Moscow Patriarch Joachim. Father Dmitry reported that he wrote the first books of lives, and they were read at the Kiev Pechersk Lavra, approved and can be printed. However, there was no response from Moscow, and the Lavra independently began publishing the works of Father Dmitry. The Patriarch, having learned about this, considered the printing premature and stopped it, but approved Dmitry himself. The manuscripts were double-checked and the books were published later.

Soon Father Dmitry had the opportunity to go to Moscow, accompanying Hetman Mazepa, who was carrying a report. The time was alarming; the archers were rioting in the capital, supporting Princess Sophia, who was trying to seize power.

Father Dmitry was introduced first to Tsar John, and then to young Peter, who was in the Trinity-Sergius Lavra, where he fled from his sister and the archers loyal to her, who were going to kill him.

Father Dmitry, having spent some time in Moscow and received a blessing from Patriarch Joachim, returned to his monastery and eagerly set to work. Now his work was important not only for Ukraine, but also for Russia.

Soon after Father Dmitry returned to Ukraine, Patriarch Joachim and Metropolitan Gideon of Kiev died one after another. The new Patriarch of All Rus' Adrian confirmed the rector of the Kiev Pechersk Lavra, Varlaam Yasinsky, who knew Father Dmitry well, as the Kiev metropolitan. From Moscow, the new metropolitan brought him a letter with a blessing to continue the work of compiling the lives of the saints. In response, Father Dmitry, thanking the patriarch, asked to send him the Great Chetya Menaion, compiled by Metropolitan Macarius in the 16th century, for the three autumn months.

Realizing the importance of the task entrusted to him, the abbot again abandoned his abbotship, sequestering himself in a secluded hermitage for in-depth work. After some time, Father Dmitry prepared a new part of the lives and took them to the Lavra printing house.

The new Kiev Metropolitan transferred Father Dmitry to Kyiv, as rector of the Kirillov Monastery, where his centenarian father continued to serve as ktitor.

But here he did not have to stay long. Every Ukrainian bishop wanted to attract him to his diocese. Therefore, Father Dmitry soon became abbot of two Chernigov monasteries, receiving the rank of archimandrite.

The new rank only added to his humility and zeal, and as before, the lives of the saints remained his main concern. Ahead of him were new books of Menaion (for March, April, May), which the Lavra printing house printed in 1700.

Emperor Peter wanted to find a clergyman to spread Christianity among the peoples of Siberia, as well as in China. Such a shepherd was awaited by the bishopric in Tobolsk, the then Siberian capital. The king decided to look for a suitable person for this person in Ukraine, where there were theological schools that trained preachers and missionaries. The king’s choice fell on Archimandrite Dmitry as “a good and learned monk with a good, immaculate life.” He was ordered to come to the capital and take two monks with him to teach Chinese and Mongolian languages.

Arriving in Moscow, the archimandrite no longer found Patriarch Adrian alive. (He turned out to be the last patriarch of all Rus' until 1917, since Tsar Peter abolished the patriarchate in 1721, and the Holy Synod headed the Orthodox Church.)

A month later, Father Dmitry was ordained Bishop of Siberia. But he soon realized that he would not be able to fulfill the duties assigned to him. His age made itself known - 50 years, and Bishop Dmitry, even in his youth, was not distinguished by good health, which was now weakened by hard work and new worries. It would have been difficult for him to endure the harsh climate of Siberia. In addition, he would not have had the opportunity to devote time to composing lives. All this alarmed Vladyka Dmitry so much that he became seriously ill.

However, to his relief, Tsar Peter, having learned about the condition of the new bishop, allowed him to remain in Moscow to await appointment to a diocese closer to the capital.

For about a year, Vladyka lived in the cell of the famous Kremlin Chudov Monastery, which was inhabited by learned monks, and was engaged in his usual work. In the capital, the Chet'i-Minei compiled by him were very fond of, which became reference books for Muscovites. People sought his company for spiritual conversation. Tsarina Paraskeva Fedorovna, the widow of Tsar Ivan Alekseevich, especially valued communication with Bishop Dmitry, often sending him dishes from her meal and clothes, thereby expressing, as was customary at that time, signs of the deepest respect.

When Metropolitan Joasaph died in Rostov, Bishop Dmitry was transferred to the empty see. And for preaching in Siberia in Ukraine, they selected another candidate, who baptized the Siberian peoples into Christ - Bishop Philotheus (Leshchinsky).

A new period of life began for St. Dmitry - he became a bishop, but, of course, he did not leave his previous occupation.

In his diary, Saint Fr. He settled in the Rostov Metropolitan Court, in modest chambers. The courtyard itself, called today the Rostov Kremlin, was surrounded by high walls with towers, and there were numerous temples and stone chambers. The cathedral church of Rostov was (and again became so in the 1990s) the monumental Trinity Cathedral. Here the Metropolitan began to conduct services and address the believers with a living word of sermon.

Having become the spiritual leader of the diocese, he introduced an atmosphere of trust and love into relations with parishioners. At the beginning of his ministry, he told them: “Let not your heart be troubled at my coming to you... let ye not serve me, that I may serve you. I came to you with love, I won’t say like a father to his children, but like a brother to his brothers, like a friend to dear friends.”

On January 6, 1703, Bishop Dmitry wrote in his diary: “... my father Savva Grigorievich reposed and was buried in the Kirillov-Kiev Monastery... May his memory be eternal.” Bishop Dmitry’s notes end with words about the death of his 103-year-old father. He no longer kept a diary, thus separating his former life with affection for his parents from the new one, full of serving God, practical affairs and worries about many people. The last years of the Metropolitan’s life were surrounded by the Rostov flock, which became his family.

Before the arrival of Bishop Dmitry, no pastoral sermons were heard in Rostov. There was no religious school in the city. The priests were not educated enough to handle the living word of the Gospel from the pulpit, not always understanding the importance of the office entrusted to them.

The Metropolitan decides to open a theological school in Rostov with his own money. It was the second school in Russia after Moscow, and 200 people could study there.

Vladyka himself directed the school and taught in it. In the summer, he invited seminarians to his country episcopal house, and during the holidays he himself taught young people.

He gave those who completed the course places in churches, where at first they served as altar servers and readers. This is how he managed to raise many wonderful shepherds. It was a difficult time. The long war with the Swedes and the consequences of the church schism weakened the state, which Tsar Peter had built decisively and with drastic measures. There was a great need for both people and funds. The bishop's house in Rostov became impoverished, but the little that St. Dmitry used, he gave to help the school, to support the clergy and impoverished people.

During the first two years of his life in Rostov, Bishop Demetrius managed to complete the last summer part of the Chetya-Menai (June, July, August) and send it to Kyiv for printing.

The Metropolitan often visited Yaroslavl, the second most important city in his diocese. One day he learned that people here were especially alarmed by Tsar Peter’s decree on barber shaving. They considered the removal of a beard a distortion of the image of God and did not want to obey the decree.

The saint later told how, after the liturgy, two not yet old people stopped him and asked:

- What should we do? Maybe it’s better to put heads on the block than to shave beards?

-What will grow faster, a severed head or a beard?

- Beard.

“Well, it’s better not to spare the beard, which grows back after shaving, than the head,” the saint jokingly resolved the dispute.

This was one of the cases of his competition with the schismatic Old Believers.

For his flock, he constantly wrote spiritual instructions in the form of questions and answers about faith.

As mentioned above, in this lean time the Rostov bishop had few funds. He didn’t even have his own horses for the necessary travel. However, he accepted poverty from an early age along with his monastic image.

At the end of his many years of work compiling the lives of the saints, Bishop Dmitry decided to acquaint readers with the history of the Church in its ancient times. To write this book, he began to collect church chronicles, Slavic, Greek, Latin. The saint plunged into new great work. However, the affairs of the diocese took up a lot of his time, and the bishop had a presentiment that this work would not be completed. And so it happened.

Surprisingly quickly, he wrote a large and complex book against the schism, collecting oral information about the sects and movements of the Old Believers. This book became the last work of the saint.

At this time he was 58 years old, of which the last seven he served in Rostov.

Feeling the approach of his hour, Saint Dmitry wrote a will, which reflected his soul, filled with love: “I have not collected any property except the books of saints, neither gold, nor silver, nor unnecessary clothes...” He gave this will to his friend, locum tenens Patriarchal Stefan Yavorsky, and they made a vow to each other that whoever outlived the other would perform the funeral service for the deceased friend.

On the day of his name day - Dmitry of Thessalonica - he served the liturgy in the cathedral as usual, but was no longer able to deliver a sermon. One of the singers read the text he had prepared from a notebook. The saint sat at the royal door, his face changed from a serious illness.

That day he had visitors for a spiritual conversation, and one nun, who lived not far from the bishop’s house, urgently asked him to visit her. The saint made up his mind and went to her, believing that the movement would be good for him, but with difficulty he made it back to his cell. He was tormented by a suffocating cough. Then he called the singers to him and asked them to perform spiritual hymns, which he himself had once composed. And wonderful chants began to sound: “My dear Jesus! I place my hope in God! You are my God, Jesus, You are my joy!”

Saint Dmitry listened attentively to the singing, leaning against the stove. Then he asked one of the singers, whom he especially loved, to stay, and began to tell him in the simplest words about his life. Then he walked the singer to the door and bowed to him, thanking him for working hard to copy his compositions. The saint dismissed all his servants, as if wishing to rest, and locked himself in his cell.

At dawn, the servants who entered found him on his knees, as if praying, but discovered that Saint Demetrius had already died.

According to custom, the large bell was struck three times. The deceased was dressed in bishop's robes, and works written by his hand were placed under his head. The whole city came to him.

Saint Demetrius was transferred to the Trinity Cathedral, where the Rostov metropolitans were buried. Requiem services were held for him for about a month. In the last days of November, Patriarchal Locum Tenens Stefan arrived in Rostov to fulfill his vow to a friend. He recalled that Saint Dmitry bequeathed to be buried in the Rostov Yakovlevsky Monastery. On November 25, accompanied by numerous clergy and people, singing and crying, the body of the saint was transferred to the place he had bequeathed.

After the death of the Metropolitan, the Menaion and other literary works he compiled continued to be favorite reading for many people. In 1763 the saint was canonized. His relics were found and placed in a beautiful silver shrine. Empress Catherine II ordered the construction of a huge Demetrius Cathedral dedicated to the saint in the Yakovlevsky Monastery. Its walls were decorated with frescoes depicting events in the life of the illustrious metropolitan. The days of his memory were always accompanied by a large crowd of people. Both ordinary people and Russian emperors came to the monastery, and everyone received spiritual help. As before, universal love for him was great. For 40 years the grave elder Hieromonk Amphilochius stayed with the relics of St. Demetrius. Every day he prayerfully stood before the tomb of his beloved saint, leaving only 5 hours for sleep.

Today, the ensemble of the Rostov Spaso-Yakovlevsky Dimitriev Monastery amazes with its beauty and power. In the summer, the monastery is buried in flowers, which St. Demetrius loved so much. In 1991 His relics, which were in the museum in atheistic times, returned to the Yakovlevsky Temple.

The great ascetic, who collected the lives of saints throughout his life, after his death was himself included in the Chetii-Minea of subsequent editions - October 4 A.D. style (the day of the discovery of the relics) and November 10 AD. style (day of death). And his books, 12 volumes of Menaion (according to the number of months), sermons and other works have been republished today and again find their readers.

Based on the life of St. Dmitry of Rostov

Olga Lashkova

The fight against schismatics

Having completed one great and soul-saving work for the entire Christian people, the Providence of God placed new concerns on the metropolitan. The future saint had to save the flock entrusted to him from the misfortune of schismatics.

Dimitry Rostovsky

In the Bryn forests adjacent to his metropolis, entire schismatic clans and sects were hiding, who sent their preachers everywhere in order to spread their false teachings. Many people, especially simple ones and not learned in the subtleties of theology, fell into their net and began to waver in the true faith.

One conversation is described that took place between the Lord and ordinary people. Once after the service, two people approached him and asked if they could shave their beards, as the decree of that time commanded. There was an opinion among the people that along with a beard, the image of God is also taken away from a person. The Metropolitan explained to them for a long time that the image of God cannot be in a beard, that it is in the human soul.

Of course, with such a level of knowledge about Christ, the people easily fell into schismatic heresy. Then the Metropolitan writes several essays on faith, in which he firmly and confidently explains what the false teaching of the schismatics consists of and why it leads away from God.

In addition, the Bishop regularly travels around the diocese entrusted to him and everywhere he personally denounces schismatics and calls on Orthodox Christians to avoid this teaching in every possible way. Being a zealous preacher and a true Christian, he cannot watch without pain how ordinary people are seduced from the true path by cunning false preachers.

What an Orthodox Christian should beware of:

- Is it possible to tell fortunes at Christmas?

- The attitude of the Orthodox Church towards curses

- Ecumenism

Other works of the holy ascetic and his spiritual gifts

Having the experience of writing a large church work, Metropolitan Demetrius decided to write another book telling about the events of the Bible. The fact is that at that time the Bible in the Slavic language was very rare and was very expensive. Therefore, the majority of the common population could not afford such luxury and were deprived of the grace-filled reading of the Holy Scriptures. Moreover, even many of the priesthood had a poor understanding of biblical events and confused chronology.

Icon of Demetrius

Saint Demetrius begins a new work. In it he uses the main biblical events and plots, and ascribes teachings and interpretations to them. By reading this work, even a person completely unfamiliar with the Bible could form a clear idea of the Holy Scriptures. Unfortunately, the saint was never able to complete this great work due to his very poor health.

In addition to writing books, the ascetic spent his entire life preaching the faith of Christ. Possessing a unique gift of speech, he knew how to structure his speech in such a way that no one who heard them remained indifferent. Since most often his listeners were ordinary people, he structured his sermons simply, like a conversation between a father and his beloved children. And no matter what labors and worries fell to the lot of the ascetic, he never abandoned the feat of preaching until the very last days of his life.

One of his ascetic deeds was prayer, which he never abandoned. Trying to be in church every day, he served the liturgy on every Sunday and church holiday. He taught everyone who was in his immediate circle to pray constantly and earnestly, remembering the Lord every minute.

Interesting! The fast of the ascetic was also very strict. So, during Holy Week he ate only once - on Maundy Thursday.

Of course, such a deep spiritual life also affected his earthly life, his communication with people. With everyone whom Dmitry Rostovsky ever met, he was attentive and courteous. All his life he helped the poor and suffering - some with words of consolation, and some with money. Saint Demetrius was distinguished by extreme non-acquisitiveness; he was always content with only the necessary minimum of goods for himself, and distributed the rest to those in need.

The result of such an attentive attitude to one’s own soul was the acquisition of the greatest humility. The ascetic always remembered the words of the Lord that whoever wants to be first in the Kingdom of Heaven must be last in earthly life. In the life of Metropolitan Demetrius, this commandment was embodied in deep respect for any superiors, mercy for subordinates, and compassion for the grieving.